And how Japan retained its writing system after WWII

After World War II, when the Allied Forces under General MacArthur occupied Japan, the country was in dire need of food, infrastructure, and all-round rebuilding. Specialists were brought in to help with every sphere of government, including American officials with expertise in education.

When these officials saw the Japanese writing system, they were dumbfounded by its complexity. Three different alphabets?! How could children learn such a complicated system?

In order to simplify education, a suggestion was put forth to scrap the three writing systems — hiragana, katakana, and kanji — and replace them with one system, the Western alphabet, known as romaji (Roman letters), which had been introduced to Japan in the mid-1800s.

Before drawing up such a plan, first a study needed to be carried out to determine the literacy of the people. If the literacy level were shown to be low, then the Western alphabet would replace the Japanese writing systems in schools.

Working at the Civil Information and Educational Section under the Office of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces was a noted linguist and scholar, Professor Kindaichi Haruhiko, who was one of those assigned to this difficult task.

He and his colleagues created a test to be administered to 10,000 people randomly chosen from family registers throughout the country. The first portion of the test would be on hiragana, the second on katakana, and the final section would be on newspaper reading and comprehension. Both reading and listening skills would be tested.

Carrying out such a study was a difficult endeavor in war-ravaged Japan, but the test was created, a one-hour time limit agreed upon, and a date was set for the test to be given.

The Old Woman of Odawara

Professor Kindaichi was assigned to a school in Odawara City, just south of Tokyo. An hour before the test was to begin, all the students were present — all except one. He checked to see who was missing. It was an elderly woman whose house in Tokyo had twice burned to the ground during the war. She was now living with relatives in Odawara.

At that time in Japan, non-compliance with authority was not an option in the collective mind, so Professor Kindaichi went to the woman’s house to collect her. When he got there, he found that she was in bed with “a fever.”

Shocked to see the professor at her house, she jumped out of her futon and knelt respectfully before him and pleaded, “Please don’t make me go. If I take this test, I will bring shame to His Majesty the Emperor.” She bowed low, her face rubbing against the tatami mat in abject humility.

Although literacy was relatively high during the Edo Era (1603–1668), compulsory education was not introduced to Japan until the Meiji Era. In 1872, for the first time in Japanese history, all children were required to attend elementary school for at least three years.

The old woman had been born long before 1872 and had never attended school. She could not even write hiragana. She had given up on learning letters, determining to learn to read and write in her next life.

She told the professor, “This is my daughter. Please take her instead of me.”

Professor Kindaichi looked at the daughter, dressed in a lovely kimono, waiting to be called with, the professor recalled, “a gravity of countenance as if she were to be a human sacrifice.”

The professor responded, “No, that cannot be. You were chosen by lot. It’s your lucky day!” He tried to cheer her with his levity, continuing, “You should go buy a lottery ticket, you’re so lucky!”

The old woman made up her mind, “I understand. I will be the one to go.” With a solemn face, she stood up, straightened her kimono, put on her haori embroidered with her family crest, and went with the professor to the school.

Finally, the test could begin.

Across the country the results were surprisingly good. There were few who got every answer correct, but almost no one had failed. The fact that each letter in Japanese has its unique pronunciation makes reading and writing relatively easy. The American officials were surprised and impressed at the results. The plans to replace the writing system were abandoned.

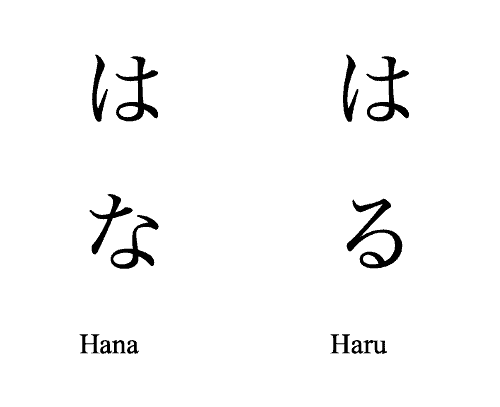

But what of the old woman? How did she manage? The professor felt sorry for her, sure that she had been embarrassed to be among the very few who scored zero. He peeked at her test, and discovered that her name was Hana. Then his face broke into a smile.

During the listening portion of the test, the students had been asked to circle the word for spring, haru, はる, on their test papers. This word included the hiragana “ha” that was in her name, Hana, はな. Of course, she could read her own name! Although everything else on the test was incorrect, she managed to answer that one question and get a score of five points. Certainly, there was no shame in that.

This story was taken from Professor Kindaichi’s book, 日本語新版、下、 金田一春彦、1988

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/