And a brief history of Christmas in Japan

When my children were young, a kind elderly friend used to ring our doorbell on Christmas eve, then proudly hand us a bucket of Kentucky Fried Chicken that included a “Christmas Cake” and a KFC commemorative plate. This was, after all, the way Americans celebrated Christmas — or was it?

A Little History of Christmas in Japan

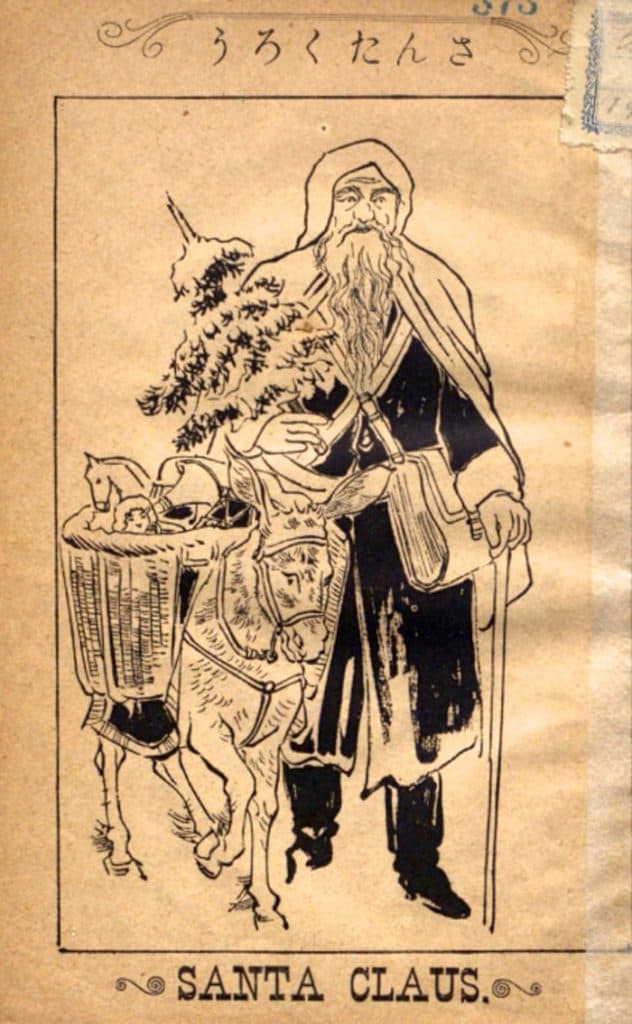

In 1560, thanks to the missionary work of Francis Xavier, the first recorded Christmas event was held in Kyoto, attended by about 100 people. In 1568, as incredible as it sounds, there is an account of the warlords Oda Nobunaga and Matsunaga Hisahide agreeing to a temporary truce over Christmas.

Just 50 years later, when Christianity was outlawed and became punishable by death under the Tokugawa Shogunate in 1613, any hopes of further Christmases were dashed. This enforced suppression continued until the country opened up to the West in the last half of the 1800s. With the influx of Western ideas, Christmas slowly seeped back in.

The first Christmas displays in Japan appeared in 1904 at the Meiji-ya department store in Ginza, Tokyo, and they attracted widespread attention. The practice spread, and other shops began decorating, restaurants and coffee shops started offering limited menus for Christmastime, and in 1910, Fujiya sold its first “Decoration Christmas Cake.”

The consumer Christmas was born.

Somewhere along the line, the knowledge that Xavier imparted about the religious significance of Christmas was lost.

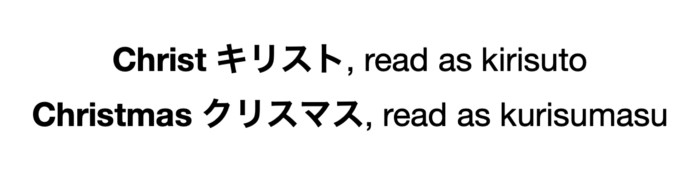

Aside from the fact that Christ is known more as Iesu Kirisuto in Japan, the words Christ and Christmas look and sound completely different in Japanese. You can see why there would be a disconnect that we English speakers wouldn’t experience.

As well, Christianity was never a popular religion in Japan. Today, a mere 1.1% are Christians.

But, back to history.

Post War Christmases

After the initial hard years following WWII, Japan’s economy began to grow at an exponential rate. Initially boosted by the production of war materials to fuel the Korean War during the early 1950s, the Japanese economy grew at an average of 10% per year from 1955 to 1973. People started to have disposable income for the first time in a generation — as well as a curiosity for things Western.

Christmas Eve soon became a night where romantic partners could enjoy a quiet dinner out, with maybe an exchange of gifts, like a Japanese version of Valentine’s Day.

While Christmas has never been a holiday, families with children began to celebrate by eating a store-bought “Christmas Cake” on Christmas night, and many gave small gifts to their children.

There were Christmas sales, Christmas music piped in at department stores, Christmas events at theme parks, and Winter “illumination” on city streets. All these customs have only increased and spread over the years.

The “Kentucky for Christmas” Campaign

How Kentucky Fried Chicken’s Christmas marketing strategy was born has almost entered the realm of urban legend.

Our first version tells of a nameless foreigner who walked into an early KFC restaurant and bemoaned the fact that there are no turkeys in Japan. (In fact, there are also no ovens big enough to cook a turkey, but I guess she didn’t get that far in her thought process.) A shrewd store manager overheard her, and the concept of marketing fried chicken as a Christmas food was born.

The former CEO of KFC Japan and owner of the very first KFC franchise in the country, Takeshi Okawara, tells a different story.

Mr. Okawara says that it all started at the 1970 World’s Fair in Osaka, where test stores for a few American fast food chains were among the exhibits. One of these was Kentucky Fried Chicken, which proved to be wildly popular, selling thousands of meals every day. Mr. Okawara, then working for Nippon Paper Company, provided KFC with the needed packaging for these meals, so during the course of the fair, he became quite familiar with the store.

Mr. Okawara was deeply impressed with Colonel Sanders’ story of eventual success after a near life-time of business failures. He saw KFC as a way to attain the wealthy lifestyle for which he yearned, so he decided to open the first KFC store in Japan. This he did in Nagoya in 1970, and in spite of KFC’s popularity at the World Fair, his shop was a dismal failure.

“I was cooking chicken and waiting, waiting, waiting, but I couldn’t sell it,” said Mr. Okawara in a 2018 interview with Business Insider.

“First of all, all the signs were written in English. The roof was painted with red and white stripes. Actually, no one knew what I was selling. People would come in and ask, ‘Is this a barber?’ or ‘Is this store selling chocolates?’”

Sales were so bad that Mr. Okawara was reduced to sleeping in the back of the shop to save money. He lived off of the leftover chicken he cooked each day. But eating all that chicken gave him hope. He loved it. He believed he would one day succeed if he kept trying.

“One day I got a phone call from a [Catholic] sister at a kindergarten. She was holding a Christmas party for the kids, and they wanted a Santa to dance in front of the children.” Mr. Okawara had attended Jesuit schools, so he was among the relatively few Japanese who were familiar with Catholicism and Christmas traditions.

“I had no other choice. She was going to buy my chicken! So I put on a Santa costume, and I started dancing holding the barrel of chicken. ‘Kentucky Christmas! Kentucky Christmas! Happy happy!’ like that, I made up a song, dancing around. And the kids liked it!” remembered Mr. Okawara.

This led to the idea of marketing his fried chicken as a Christmas food, which, according to the KFC website, began in 1974. He put a Santa costume on the Colonel Sanders statue in front of the store and came up with the slogan, kurisumasu ni wa kentakkii, Kentucky for Christmas.

This brought a measure of success. But his real breakthrough came after an interview with the Japan national broadcasting station, NHK.

According to Mr. Okawara, he was asked, “You are selling so much chicken during Christmas. Is [eating chicken at Christmas] a common custom overseas?”

Knowing how cool and popular things Western were to the Japanese in those days, he couldn’t help himself. Mr. Okawara replied, “Yes.”

And the rest is history.

From that one struggling store in Nagoya in 1970, by the end of 2020 there were 1,138 KFC restaurants in Japan, where one regular Kentucky Christmas bucket is sold for ¥4,100 ($37). The bulk of KFC’s sales is in December — pre-ordered buckets for the 25th — which in 2020 accounted for 1/3 of their ¥114 billion ($1,010,838,000) yearly profit.

So, do I eat KFC for Christmas?

Our dear elderly friend has passed away, as has our custom of eating KFC on Christmas Eve.

Each year, I buy a whole chicken from a local shop that specializes in chicken sashimi — chicken that people eat raw. Yes, raw chicken is one of the delicacies to be enjoyed in Kagoshima. Because this chicken is intended to be eaten raw, it is extremely fresh.

On Christmas evening, my family dines on roast chicken, which, in spite of Mr. Okawara’s little white lie of desperation, is closer to the actual tradition in my home country of America.

Sources:

https://japan.kfc.co.jp/assets/articles/1846/files/269, https://jpnculture.net/christmas/, https://www.kfc.co.jp/lp/xmas2021/, https://global.kfc.com/stories/how-kentucky-for-christmas-began-in-japan/, Brought to you by… Business Insider podcast, https://www.bunka.go.jp/tokei_hakusho_shuppan/tokeichosa/shumu/index.html

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/