Old and new ways to ring in the New Year

After first arriving in Japan in 1987, I quickly learned to stock up for the first three days of the New Year since all stores would be shuttered while their owners and employees spent time with their families.

Times have changed. Today most stores remain open during the holidays and 24-hour convenience stores abound.

While modern times have brought welcome changes, perhaps along the way some of the understanding of the holiday customs has been lost, cast aside amid the hubbub of TV specials and New Year’s Sales.

To understand Japan’s New Year, we need to return to the holiday’s roots, which date as far back as the 1st century. In those days, the ancient people celebrated in three main ways.

- Welcoming the toshi-kami, the god of the new year.

- Praying for bountiful harvests in the coming year.

- Expressing gratitude for another year of life.

These practices are reflected in today’s New Year’s traditions, and each of the holiday’s countless customs is imbued with meaning.

Let’s take a look at a few of the most outstanding traditions, work our way forward in time, and end with a look at those TV specials.

Welcoming the God of the New Year, the Toshi-Kami

The Shinto Toshi-kami descends from the heavens via the pine decorations that adorn each house. Around the time families break and eat their kagami mochi, the New Year’s decorations are ceremonially burned—typically around January 15th, depending on regional customs—the smoke transports the god back to the heavens, leaving behind his blessings and protection for the year ahead.

This Toshi-kami is a busy god with a wide portfolio. Besides being the god who brings bounty and blessings in the new year, he also merges with the collective spirit of each family’s ancestors, their sorei, who visits their family at this time (although the sorei’s main holiday is Obon, in the summer). The Toshi-kami then becomes a ta no kami, rice field god, in the spring, and a yama no kami, mountain god, after harvest in the fall. He is also sometimes known as the god of lucky directions.

Reflecting the importance of purity and cleanliness in the Shinto religion, a thorough house cleaning is done at the end of December. People get rid of clutter, dust behind cabinets, change the paper in the paper doors, and make their houses spotless. Once that is done, Shimenawa ropes are hung upon the doorways signifying that the house is purified and ready to welcome the Toshi-kami.

Gratitude for Another Year of Life

Long ago in Japan, in accord with the Chinese method of counting years, newborns were considered one year old, and another year of life was added to everyone on New Year’s Day, regardless of their birthdays.

Gifts of Money, O-Toshi-Dama

As a kind of birthday present on New Year’s Day, children receive small envelopes filled with money for the year from each of their older relatives. This money is called o-toshi-dama, お年玉, literally “honorable year’s jewels.” Since Christmas is a fairly recent import into Japan and not a holiday (see my brief history of Christmas here), New Year’s Day is the day children have traditionally looked forward to receiving gifts, i.e., money.

Special New Year’s Dishes, Osechi-ryori

In order to take a holiday from cooking and enjoy time with one’s extended family, special foods are painstakingly prepared in advance — or bought — to be eaten together with the Toshi-kami during the first three days of the new year. Eating these meals with the gods is said to impart spiritual power and blessings upon the mortals.

Each food has its specific meaning, and there are too many to mention, but here are a few.

Sea Bream — Tai, for an auspicious year

The traditional Japanese calendar started in spring and so New Year’s Day used to be a springtime occasion. From the image of the first sprouts appearing came the expression mede-tai, 芽出度い (pronounced meh-deh-tie), literally “the time when sprouts emerge.” From that, mede-tai came to be used to describe something happy and auspicious.

For this reason, sea bream, called tai, 鯛, is an essential part of any osechi-ryōri. It plays on the homonym tai, “happy” and “auspicious” — everyone’s sincere wish for the new year.

Herring Roe — Kazunoko, for many children

Another popular item is herring roe, called kazunoko, 鯑. Its homonym means many children, 数の子.

Shrimp — Ebi, for long life

As a wish for long life, shrimp are eaten. Shrimp, called ebi, 海老, literally “the aged of the sea,” suggest the long beards and bent frames of the elderly.

Dried Sardines — Tazukuri, for bountiful harvests

Tazukuri, 田作り, is a dish made of dried sardines and soy sauce. Its name means “making a rice field.” Sardines were traditionally used as fertilizer in rice paddies in many areas of Japan, thus the dish expresses the wish for abundant harvests.

Rolled Omelets — Datemaki, for days of blessings

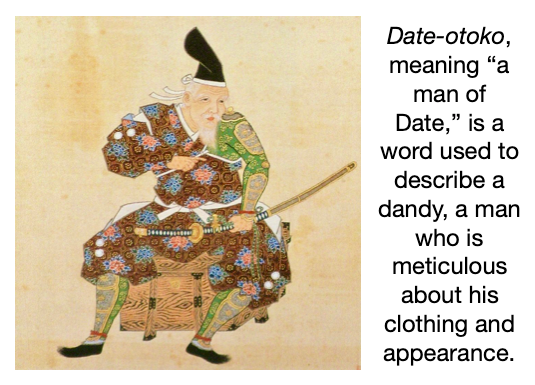

Perhaps my favorite wordplay is the name for the rolled, sweet omelet mixed with fish paste. It is called datemaki, 伊達巻 (pronounced dah-te-ma-key), so named because the samurai lords of Sendai (in Miyagi Prefecture), the Date clan (dah-te), were famous for being well-dressed.

In ancient Japan, holidays were called hare no hi, ハレの日, special days, and on such days people wore their finest clothes — what we might call their Sunday best.

From this idea of fashionable Date clan style clothing being worn on special days, the Date-maki sweet omelet expresses the wish for many such special days in the coming year.

Bell Ringing

From the introduction of Buddhism in the 6th century, Buddhist customs merged with the ancient Shinto customs. As such, at midnight on New Year’s Eve, Buddhist temple bells are rung 108 times, banishing the 108 worldly desires. This marks both a prayer for forgiveness for the past year, and a prayer for steadfastness in the next.

First Shrine Visit of the Year, Hatsumōde

On the first three days of the New Year, people flock to Shinto shrines, and many to Buddhist temples, for their first visit of the year, called Hatsumōde. Meiji Shrine in the center of Tokyo traditionally receives over 3 million visitors each year during the New Year’s holidays, but even small countryside shrines get plenty of visitors.

Visitors to shrines clap, bow, and say a brief prayer for the year. People often buy omikuji, little slips of paper picked out from a box with their fortunes for the year foretold. If they are worried that not all of their fortune is good, they can tie the paper to a tree or a wire hung at the shrine, and leave that undesirable fortune in the hands of the gods, carrying the good fortune home in their hearts.

As all their previous year’s omamori (good luck charms), daruma dolls, and household protective amulets were brought to shrines to be burned at the end of December, people buy new charms for such things as safety and protection for the new year, success in studies, or safe childbirth, new daruma for setting goals for the year, and new ema upon which to write their prayers.

Nengajo, New Year’s Greeting Postcards

On New Year’s Day, bundles of postcards are delivered to each house. These are sent by friends and associates containing words of thanks for past kindnesses, well-wishes, and yoroshiku-onegaishimasu — please, and thank you in advance — for kindnesses in the new year.

People spend time during the day nibbling on osechi-ryōri, reading over the various greetings, and remembering old friends. The cards are usually themed according to the animals of the Chinese zodiac, 2022 being the year of the Tiger.

TV Specials

A big event in many households is the yearly New Year’s Eve TV specials. The most famous by far is a good-natured singing contest, Kōhaku Uta Gassen. Musicians are divided into two teams, a red team composed of females, and a white team composed of males. The red and white division of teams gives the show its name, Kōhaku, meaning red and white.

NHK, the national TV broadcasting corporation, began airing this show from the year Japan got its first TVs, 1953. Musicians are chosen by invitation only, and performing on Kōhaku is considered quite an honor and even can be the highlight of one’s career. The spectacular lighting, costumes, and set design never disappoint.

At the end of the show, the audience, together with the judges, votes on the winning team.

Competing with Kōhaku for viewers is a bizarre show that is popular among many of the younger generation, called, Dauntaun no Gaki no Sukaiyaarahende! which defies translation.

On this year-end special, serious celebrities face off against several old-school comedians who are placed in various situations — on a bus, then in a school, or whatever the theme is that year — and the celebrities do and say outrageous things to make the comedians laugh.

If they laugh, which they inevitably do, people dressed in commando camouflage jump out and spank them with rubbery batons. The absurdity of all this is considered hilarious.

Japanese TV, truly unique, has to be seen to be believed.

This is by no means a complete list of New Year’s customs. Other traditions include making and eating delicious pounded sticky rice cakes called mochi, children flying kites in the clear breezy skies of winter, and eager shoppers hunting for “lucky bags” filled with mystery discounts at their favorite stores. In a small fishing port on the Izu Peninsula, on finds a unique New Year’s decoration welcoming the god of the New Year—Shiokatsuo, and ancient type of dried bonito. Even one’s first dream of the year is significant, but I think only in Japan does one hope it contains Mount Fuji, a hawk, or an eggplant.

By January 4th, people begin to go back to their normal routines, greeting coworkers and associates by saying akemashite-omedetō-gozaimasu, “Happy New Year,” and naturally, “For this year, too, please and thank you in advance,” kotoshi-mo, yoroshiku-onegaishimasu.

Sources:

https://maminyan.com/shogatsu/know/toshigamisama.html, https://www1.nhk.or.jp/kouhaku/, https://www.ntv.co.jp/gaki/, many years in Japan.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/