Your Guide for Choosing Sake

Contents:

- How sake is made

- Types of sake

- Importance of milling percentage

- Which sake should I buy?

- Storage and serving

- How to read a sake label

- Quantities

Several of my adult children who live in the US have become experts at making sushi, but they sometimes wonder what kind of sake to buy to drink with it. I understand. Just looking at an array of sake bottles with their mystifying Japanese labels can be daunting. And there are so many different types to choose from!

A Japanese expression, 酒屋万流, sakaya-banryū, meaning “there are 10,000 different ways to make sake,” aptly describes this vast variety. Though sounding like hyperbole, this seems to be true. Wherever in Japan you travel, you will always find unique and wonderful local sake which is not to be passed up.

Although the choices are innumerable, sake can be divided into a few main categories. Once you understand those, learning what you prefer and how to choose it becomes much easier.

First, let’s look at how sake is made.

How sake is made

Rice

The main ingredient in sake is rice. Sake rice differs from table rice in two main ways.

- Sake rice plants are taller, which makes it harder for them to survive the storms and typhoons that hit Japan during late summer and autumn. If the tall rice plants fall over into the muddy paddy, the rice can be ruined. Because of this fragility, sake rice costs about twice as much as koshihikari or other fancy Japanese table rice, like what you would find in a high-end sushi restaurant.

- Sake rice grains are larger and they have a white center that holds a high concentration of starch. This starch is converted to sugar in the brewing process.

Milling

The outer layer of rice grains contains protein and fat, which is good for eating but not for brewing. Therefore, sake rice is first milled to remove the outer layer. The unused milled portion of the grains is often used for animal feed or for making senbe rice crackers.

Koji Mold

Once milled, the rice is steamed, cooled, and spread with koji mold spores, Aspergillus oryzae. This rice is left in a 40-42˚C room for 48 hours for the mold to grow. Workers turn and spread the rice every 2 hours around the clock. They crumble the balls of rice that form due to the koji growth to keep the mold growing evenly.

Brewing

Steamed rice, water, koji rice, and yeast are added to a vat and left to ferment. Over the next few days, more rice, water, and koji rice are added. The brewing process can take from days to weeks, depending on what the brewer is making.

Until the 20th century, most yeast used in brewing sake came from the cedar walled, brewery building itself, and/or former batches of sake. From the early 1900s, the Central Brewers Union started providing pure yeast strains to brewers across the country. Each strain was given a particular number. You might see the number of the yeast strain that was used to make the sake listed on the bottle’s label.

Sake is initially brewed to an alcohol percentage of 18% or higher. To make it suitable as a table beverage, water is added. This reduces the alcohol content to typically around 15%.

Genshu, 原酒, is sake to which no water has been added. This higher alcohol, yellowish sake has become popular in recent years.

Pasteurization

Most sake is pasteurized before storing and, again, before shipping. This is done to prevent spoilage, stop the fermentation process, and standardize the quality.

You can buy unpasteurized sake. If you do, you will need to keep it in the refrigerator and finish the bottle within a week. These kanji will be in a prominent spot on the label: 生酒 要冷蔵, namazake yōreizō. ‘”Unpasteurized sake — needs refrigeration.”

Sugidama

When a fresh batch of sake is made, brewers have traditionally hung a fresh, green ball of cedar called sugidama from the eaves of their shop. When the green has completely faded to brown, everyone will know that the sake has aged enough to be ready for drinking.

Although the length of brewing time now varies, you can still see sugidama hanging in front of sake brewers and sometimes even sake shops and bars.

Types of sake

There are two main categories of sake, junmai and honjozo. These differ in just one ingredient.

Junmai 純米

Junmai means “pure rice,” and as such, junmai sake is made from only rice, koji, yeast, and water.

Honjozo 本醸造

Honjozo is made from rice, koji, yeast, water, and distilled alcohol.

Why is alcohol added to sake? In the past, it was added to prevent spoilage. Today, brewers add alcohol to enhance the flavor and aroma of their sake, which results in a marvelous variety of honjozo sake, well worth trying.

Importance of milling percentage

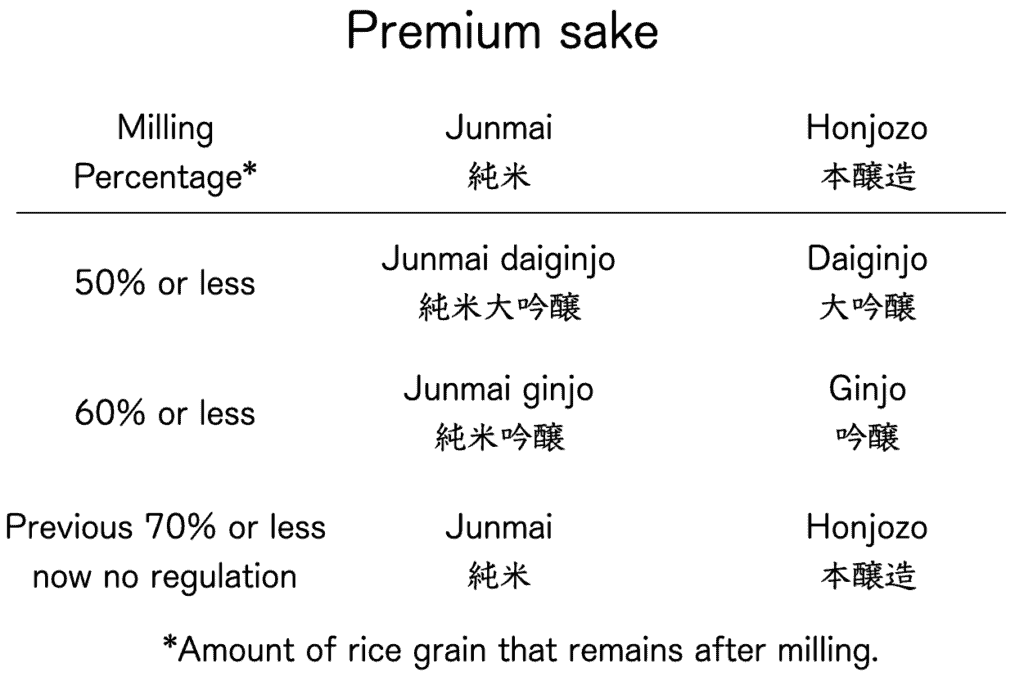

Junmai and Honjozo are divided into categories according to the percentage of rice that remains after it has been milled.

Years ago, junmai sake was made from rice that was 70% milled. This means that 30% of the rice grain was removed with 70% of its weight remaining. Today, there is no such regulation. This allows for a huge variety of flavors among the junmai sake family.

Generally speaking, the lower the milling percentage, the higher the quality of the sake.

Which sake should I buy?

You can’t go wrong with any sake labeled ginjo, 吟醸. This is high-quality, aromatic sake brewed with special care.

Sometimes sake makers produce a seasonal sake or some other type they don’t usually make. This will be called “special” sake. There are no rules that govern the use of that word. It is up to the brewer’s discretion.

If you come across a bottle with the “special” label, it’s a good bet that it will be a fantastic bottle of sake. Look for 特別, tokubetsu, which means “special.”

特別純米, tokubetsu-junmai or 特別本醸造, tokubetsu-honjōzo.

Storage and serving

Sake should be kept out of the sun and in a cool place. Store any open bottles in the refrigerator and finish them within a week.

Cold sake

The aromatic ginjo is best served cold. Sake served cold is called reishu, 冷酒. This can be served in wine or sake glasses.

Warm sake

Junmai and honjozo may benefit from heating to 30-40˚C. Warm sake is called kanzake, 燗酒. It is often warmed in a tokkuri bottle (徳利) and served in small cups.

How to read a sake label

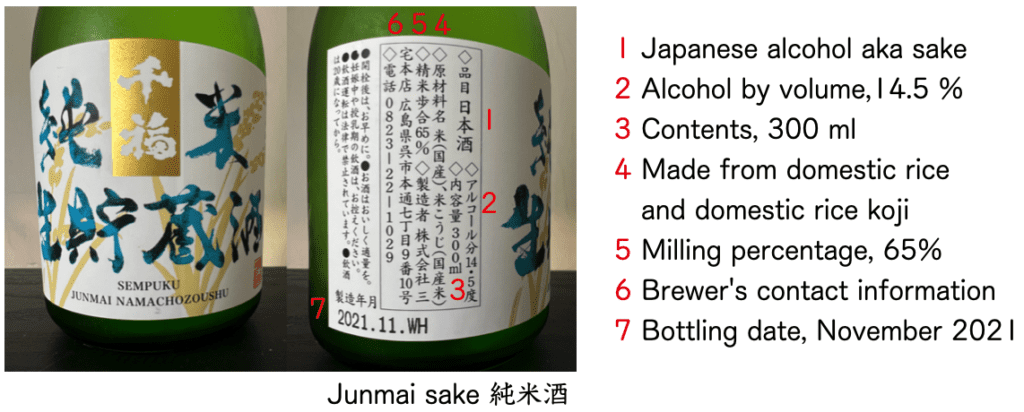

This label just contains the basics. It is translated from right to left.

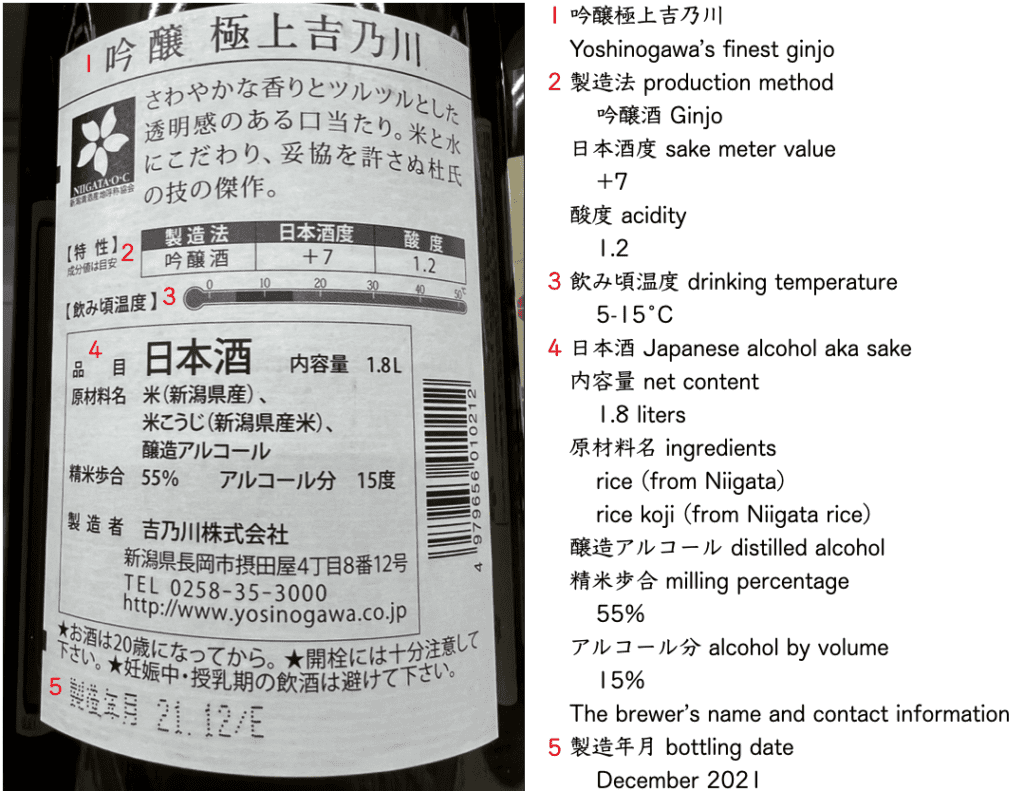

Other labels give more detailed information, such as the following:

日本酒度, nihonshudo, sake meter value.

This is represented by a + or – sign before a number.

– is sweet. + is dry. 0 to +5 is considered normal. +4 is average.

酸度, sando, acidity.

1.3 to 1.7 is typical.

使用酵母, shiyōkōbo, the type of yeast used.

This refers to the standardized yeast strains provided by the Central Brewers Union. #7 is the most commonly used strain. Highly aromatic #9 is customarily used for daiginjo.

The following label leaves out the strain of yeast used, but it still contains plenty of information.

Quantities

180 ml is called 一合, ichi gō, and is the base measurement for sake. If you order sake in a restaurant, this is what you generally will get.

Multiply ichi gō by 4, and you get the average sake bottle of 720 ml. This is called a shi-gō bin, literally “4 times ichi gō bottle.”

Multiply ichi gō by 10, and you get 1.8 liters, or 一升, isshō.

Multiply isshō by 10, and you get 180 liters, or 一石, ikkoku. These are the huge barrels of sake that you sometimes see offered at shrines. In the Edo Era (1603-1867) these straw-wrapped barrels were shipped by sea from Hyogo to Tokyo in a bustling and competitive sake trade.

In recent years, 300 ml bottles of sake have become widely available.

I hope by the next time my children make sushi, they will be able to choose a great bottle of sake to drink with their meal.

Sake is the perfect beverage to enjoy at a hanami — traditional cherry blossom viewing party — while you eat your picnic under the gently falling petals. To read more about the Japanese custom of hanami, click here.

For a clear, illustrated guide on the sake brewing process, visit this helpful website.

Sources:

http://www.japansake.or.jp/sake/english/howto/process.html, http://www.esake.com/Knowledge/Ingredients/Yeast/yeast.html, and the brilliant and knowledgeable Shima.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/