How are the mighty fallen!

Fujiwara Hirotsugu was a member of the powerful Fujiwara clan. This family influenced and manipulated emperors from behind the scenes for over three centuries during the Nara and Heian eras (710-1185).

Background on the insurrection

Starting in the 7th century, Japan’s imperial court sent missions to Chang’an, the capital of Tang Dynasty China, to import information and technology. In 717, among the scholars sent to China were Kibi no Makibi and the monk, Genbō. These two men spent 17 years in Chinese libraries and at the feet of sages.

When Genbō returned, he brought with him sutras and esoteric Buddhist texts. He soon found himself in the exalted position of abbot of the Fujiwara family’s tutelary temple, Kōfukuji, which still stands in Nara.

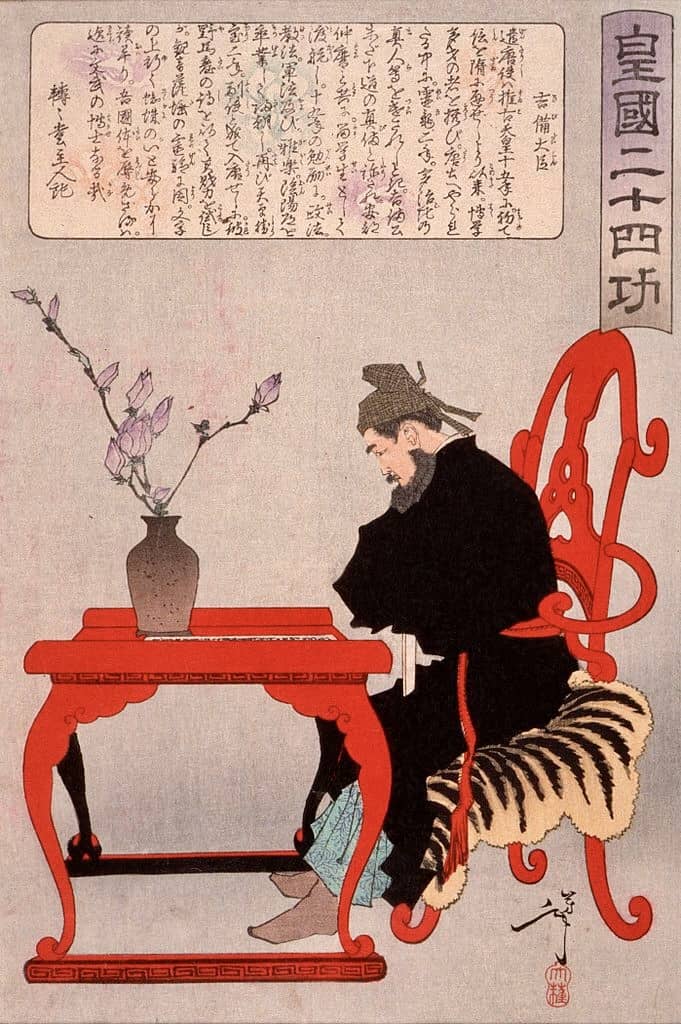

Kibi no Makibi brought back a wide variety of knowledge — academic texts, particularly those dealing with mathematics and astronomy, fine embroidery techniques, and even the game of goh. Several years later, he went back to China for further study. When he returned to Japan, this exceptional man was advanced to the third highest position in the country, the Minister of the Right.

In 735, a smallpox epidemic broke out in Kyushu and spread northeast, eventually killing one-third of the population. By 737, the epidemic reached Heijō-kyō, the capital (Nara City), causing death and terror among the aristocracy. Emperor Shōmu was spared, but ten top officials died, including the “Fujiwara Four” — Umakai, Maro, Muchimaro, and Fusasaki. Their deaths dealt a serious blow to the Fujiwara clan.

Perhaps because of this weakening of Fujiwara influence, Emperor Shōmu had Umakai’s son, Fujiwara Hirotsugu, demoted from his position as governor of the central Yamato Province and sent to be vice-governor of Dazaifu in 739. Although Dazaifu was considered the Western Capital, being banished to what Nara aristocrats thought of as an unsophisticated rural backwater on the island of Kyushu was not something anyone wished for.

Fujiwara Hirotsugu felt a great injustice had been done. He found scapegoats in Genbō and Kibi no Makibi, whom he railed against, blaming them for the epidemic, the corruption, and the general discontent in the capital.

Hirotsugu remonstrated the court, “The failures of recent policies have brought on catastrophes of heaven and earth.” He demanded that Genbō and Kibi no Makibi be dismissed.

Four days after the court received his letter, Hirotsugu declared himself in rebellion.

Fujiwara Hirotsugu’s rebellion, 藤原広嗣の乱

Life was hard for the people of Kyushu. The smallpox epidemic, years of drought, and bad harvests had made daily life miserable. The government’s response to their hardships was not to send aid but to commission a large-scale temple-building project to appease the gods. Peasants could not afford the taxes or the servitude required for temple construction.

Farmers, local district chiefs, and members of the already disgruntled Hayato minority joined Hirotsugu in rebellion. He also appealed for the support of the Korean Kingdom of Silla. Using his official position at Dazaifu, Hirotsugu soon raised a force numbering 15,000.

Emperor Shōmu was concerned not only about Hirotsugu but also about Silla’s possible involvement and its repercussions. He was eager to suppress this rebellion, but it would take time to assemble troops. All draftees had been released from the imperial military the year before due to the smallpox epidemic.

While waiting for his troops to be gathered, the newly appointed Tai-Shogun, Ono no Azumabito, sent 24 Hayato warriors from the capital to do reconnaissance in Kyushu. These men were from southern Kyushu, but as part of their taxation, each adult male was required to stay and work in the capital for six years. Unlike the people in the Yamato area, these “barbarians” were of a different ethnic and language group.

Azumabito’s army also recruited elite mounted archers from across the island of Honshu, weighing the advantage heavily in the government’s favor.

Before leaving Nara with his newly recruited army of 17,000, Azumabito was ordered to pray to Hachiman, the Shinto protector of warriors. A messenger was sent to make offerings at the Ise Shrine, and Emperor Shōmu ordered that seven-foot tall statues of the Buddhist bodhisattva, Kannon, the deity of mercy, be cast and sutras copied and read in all provinces.

Fujiwara Hirotsugu’s battles in Kyushu

Hirotsugu’s rebellion seemed doomed from the start. One of his armies did not show up for the first battle. Another was late. Hirotsugu was defeated.

He regrouped and organized another attack on Azumabito’s forces. Despite having used his position in Dazaifu to recruit armies from across Kyushu, his forces had difficulty remaining loyal.

To make matters worse, Emperor Shōmu sent a decree to the officials and the general populace of Kyushu, promising a reward to the person who could bring him Hirotsugu’s severed head.

Only a few weeks after his first battle, Hirotsugu was down to 10,000 horsemen. They faced off with 6,000 of the government’s forces at the Itabitsu River in northern Kyushu. Hirotsugu ordered his advance guards, made up of Hayato warriors, to build a raft and cross the river.

On the other side, Azumabito ordered his Hayato warriors to tell Hirotsugu’s Hayato to surrender. The armies heard them call across the river, yet only the Hayato could understand.

Then Azumabito hailed Hirotsugu again and again — ten times. Nonplussed, Hirotsugu rode to the riverside and called, “I hear someone from the court has come.”

“That’s me,” answered Azumabito.

Hirotsugu dismounted, bowed, and said, “I have nothing against the court. I just beg the emperor to punish those troublemakers Kibi no Makibi and Genbō. If I oppose the throne, the gods of heaven will punish me.”

“If that be the case, why have you raised an army and come to fight us?”

With no words, Hirotsugu mounted his horse, turned, and rode back to his troops.

Hearing this conversation, three of Hirotsugu’s Hayato leaped into the river and fled to the government side. Azumabito’s Hayato pulled them out of the water. When the rest of Hirotsugu’s Hayato saw this, they, along with ten mounted soldiers, crossed the river and surrendered.

Having been Hirotsugu’s advance troop, the knowledgeable Hayato betrayed his strategies and plans to Azumabito.

At the next battle, Hirotsugu was soundly defeated.

Escape and dishonorable death

Faced with defeat, Hirotsugu escaped across the sea, hoping to find refuge in the Korean Kingdom of Silla. But as he neared an offshore island, a fierce wind arose and prevented further progress. Hirotsugu cried to the heavens, “I am a great and loyal subject. The gods will not desert me. God, calm the winds and waves!”

Saying this, he threw his eki-rei (bell given to high officials) into the sea. The wind and waves only grew more tempestuous. He reversed course, driven by the winds back towards the Goto Islands, off the coast of what is now Nagasaki.

He arrived at the northernmost Goto Island, but instead of comfort and a warm bed, he was captured. His severed head was washed, packed in salt, and presented to the emperor in Nara.

One can only wonder if Hirotsugu remembered his prophetic words as the winds opposed his progress and he soon faced death,

If I oppose the throne, the gods of heaven will punish me.

References:

Heavenly Warriors: The Evolution of Japan’s Military, 500–1300, Kotobank Fujiwara Hirotsugu no Ran, The Literature of Travel in the Japanese Rediscovery of China, 1862-1945, and Professor Nakamura.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/