Aomori Prefecture’s Lake Towada is gorgeous

When I first read about Lake Towada in my Japanese geography and history studies, I was so captivated by its beauty that I knew I had to visit.

I got my chance in 2021. JR East had made its bargain rail passes available to foreigners living in Japan, and I jumped at the opportunity.

On a bright October day, I flew into Haneda Airport in Tokyo from my southern city of Kagoshima, picked up my rail pass, and took the bullet train to Hachinohe, on the Pacific coast of Aomori.

It was a short walk and a quick bit of paperwork to get the rental car I had reserved, and I was ready to head towards Lake Towada on the border of Aomori and Akita Prefectures.

After a 90-minute drive on country roads, with the final stretch narrow, dark, and winding, I arrived at the hamlet of Yasumiya on the shore of Lake Towada.

I checked into the enormous hot springs hotel I had reserved. The huge lobby resembled a museum with works of art, signature boards of famous sumo wrestlers, and even festival floats displayed. A waterfall fell along the stone wall down between the onsens on the ground floor.

I was one of only a few guests. Most wings of the hotel were blocked off.

Lake Towada Legend

Lake Towada was formed from numerous volcanic eruptions resulting in a broken crater lake within a larger crater lake.

It has long been considered sacred. Pilgrims would travel from far and wide to visit the lake. Tired from their travels, they would rest by the shore, which gave the town its name, Yasumiya 休屋, “resthouse.”

According to legend, a Shinto priest named Nansobo, after completing his pilgrimage to Kumano (in Wakayama prefecture), determined to continue his ascetic practices by walking throughout the country.

Instead of the usual straw sandals, he strapped on iron sandals. “Wherever my sandals give out, I will make my home,” he said as he set off, staff in hand.

He walked for weeks. When he reached Lake Towada in the far north, his sandals finally gave out.

Nansobo learned that an 8-headed dragon, Hachirotaro, ruled the lake. Once a local hunter, he had transformed into a dragon and had been ruling the lake from its depths for centuries.

The priest Nansobo himself transformed into a 9-headed dragon and battled fiercely with Hachirotaro for 7 days and 7 nights. Emerging victorious, Nansobo entered the lake as its new divine spirit.

From then on, people would come to the lake to partake of its magic. They offered money or rice twisted in white paper, coins, swords, and mirrors as prayers to Nonsobo, now Seiryu Daigongen, 青龍大権現, the azure dragon deity who inhabited the lake floor.

That is, until 1872 when the government ordered the division of Buddhism and Shinto. At that time the shrine was rededicated to the Shinto deity, Yamato Takeru, a semi-legendary 1st-century prince.

In the early 1900s, divers searched the lake bed and recovered a treasure trove of swords, old coins, and brass mirrors that had been offered to the azure dragon. Some of these are on display at a small, lakeside museum.

People continue the tradition of offering prayers at Lake Towada. But now, only prayers twisted in bits of white paper are tossed into the water, no more swords or mirrors.

The way in which the papers float reveals to what degree one’s prayers will be answered. Vertically floating papers whose loose ends point down receive no answer. Horizontally floating papers are half answered. And those that float vertically with their loose ends at the top are fully answered.

Mining Town

Although pilgrims visited Towada over the centuries, the first settlements were founded in 1869, at the beginning of the Meiji Era (1868–1912). Soon after, gold and silver veins were discovered in the western mountains and miners flocked to the town.

Unfortunately for them, due to the steep waterfalls of the Oirase river that flows from the lake, no fish had ever made it to Lake Towada. The men suffered from weakness due to the lack of protein in their diet.

One miner quit the mines and set out to resolve this problem. In 1902, after nearly 20 years of failures and setbacks, Wainai Sadayuki succeeded in breeding himemasu, a variety of sockeye salmon from Hokkaido, in the lake. The men were saved and a local delicacy was created.

Today, the healthy populations of himemasu and other varieties of fish introduced by Wanai have made Towada a popular fishing spot.

Towada’s Popularity Grows

Fuji for mountains, Towada for lakes.

Both peerless for beauty.

So wrote the poet Omachi Keigetsu, 大町桂月, in a popular magazine after he first visited Towada in the early 20th century. His enthusiastic admiration for the beauty of Towada, along with the Oirase gorge and the Tsuta lakes to the north, brought a surge of popularity to the region.

As more and more people visited, Keigetsu sought to have the lake protected. He advocated for national parks to be established in Japan — first and foremost, the Lake Towada area.

Although he died in 1925 and was buried in Tsuta, just north of the lake, his efforts were not forgotten.

In 1931, the Japanese government passed the National Parks Act. Three years later, the first national parks were established. And in 1936, Towada was made a national park.

The Maidens

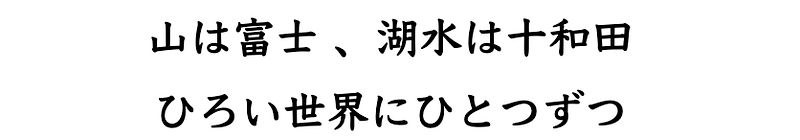

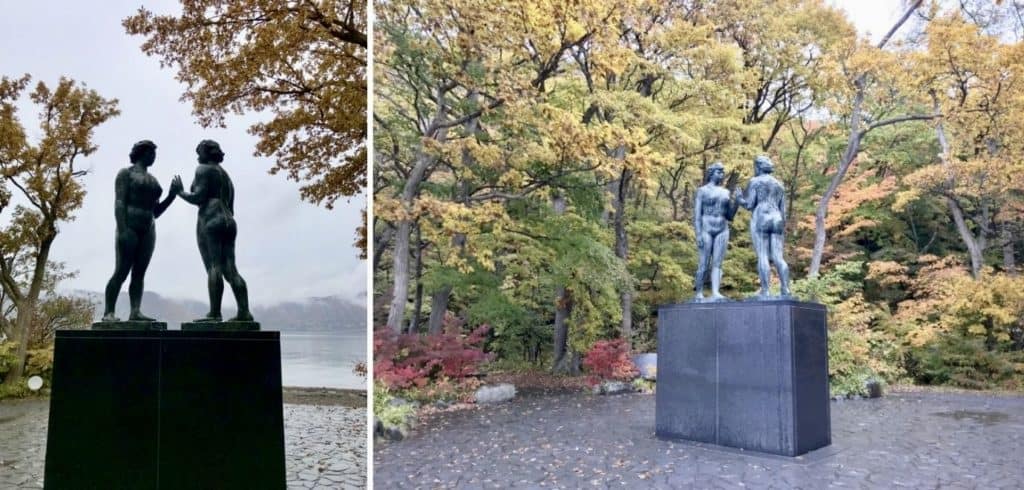

In 1953, the poet and Western-educated sculptor Kotaro Takamura created his statue of The Maidens, 乙女の像, to mark the park’s 15th anniversary. Located between Towada Shrine and the lake, it remains, as Takamura wrote, “standing silently through the ages.”

Beginning in the mid-1950s, Japan’s economy experienced decades of unprecedented growth. Lifelong employment companies became the norm, and those working for such companies were required to participate in yearly, mandatory group vacations. Towada was a popular destination.

Huge groups of company employees followed two abreast in lines behind ladies dressed in smart uniforms, flags held high in their white-gloved hands. These groups followed their guide along the lakeside to view the statue of The Maidens and pay their respects at Towada Shrine.

Then they would all pile into one of the huge boats that circled the lake, loudspeakers blaring tourist commentaries.

The salarymen would then fill the many souvenir shops that lined the lake, shopping for gifts to bring to friends and acquaintances back home, before heading to their hotels to relax in the hot springs and enjoy a feast of food and sake.

In the early 2000s, thanks to these huge group tours, the number of visitors to Lake Towada peaked at 3 million per year.

Times have changed.

Ghost Town

When I awoke to a fresh morning on my first day in Towada, I found a ghost town. Although a few shops were open, Yasumiya’s many shuttered buildings, closed businesses, and unused oversized hotels are a silent relic of its past heyday.

Restaurants were scarce, and the one I found that was open in the evening only took reservations made a day ahead. There were no supermarkets or convenience stores.

If you wish to stay there, it’s best to plan your meals ahead.

Despite, or perhaps because of, its fallen popularity, the area’s pristine beauty thrives.

Driving around the lake I discovered a sea of koyo (also written kōyō), colored autumn leaves, disappearing into the distant mist. This vast forest is protected and never fell prey to reforestation with Japanese cedar that has caused so much trouble with the ecosystem in other areas of the country.

Later, I walked by the lake and took in the birdsong, the flutter of the leaves, and the gentle sounds of the water.

Towada is also the perfect place from which to explore the magnificent, breathtaking, and otherworldly Oirase Gorge along the river that flows north from the lake.

References:

https://nyanto-matatabi.com/towadajinja/, https://towadako.or.jp/rekishi-densetsu/otomenozou/, https://www.city.towada.lg.jp/shisei/about/kouryu/oomachi.html, signs, books, and visiting.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/