Love of nature is the essence of Shinto

You can’t help but notice signs of Shinto everywhere in Japan, from impressive torii gates in front of the shrines sprinkled throughout cities and the countryside to tiny conical piles of salt on either side of shop doors.

But what is Shinto? And why are there piles of salt by people’s doors?

Shinto’s roots

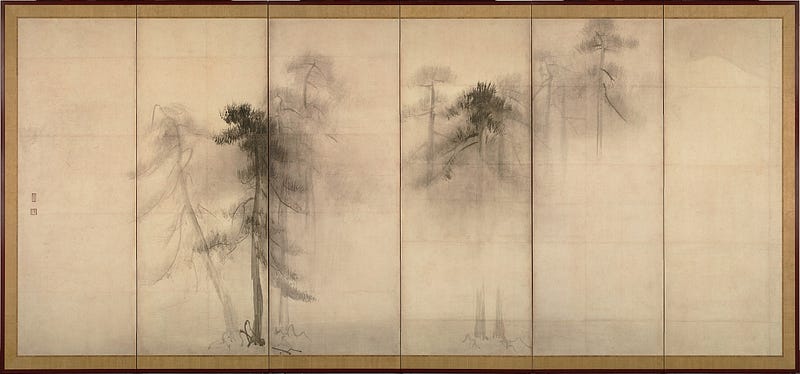

From time immemorial, people in Japan have loved and revered nature as a gift of the gods. They instinctively felt it was their duty to care for the natural world. And they realized that in order to live in harmony with nature, they needed to both receive its blessings and gracefully accept its ravages.

Shinto was born from this sense of awe and respect toward the power and beauty of nature and gratitude for its bounty.

Shinto deities or kami

Heaven, earth, and mankind all manifest nature’s energy. This natural energy, or life force, is what Shinto calls kami.

Life force is everywhere and in everything, so there are kami of mountains, wind, waterfalls, trees — all kinds of things. Shinto recognizes the great power and influence these have over our lives.

Since natural landmarks were places where kami resided, structures were built near them where rituals could be conducted. This is the origin of Shinto shrines.

Not only natural objects, but people who have made great contributions to society may be enshrined as kami, such as Sugawara no Michizane, the kami of learning, and Wake no Kiyomaro, the Great Protector of the Emperor.

A religion with no creed

Shinto has no founder, no creed, and no commandments. There is no one omnipotent creator god.

Shinto kami are not infallible gods. In fact, they are a lot like us.

When faced with a problem, kami gather to discuss how to solve it. This decision-making by committee was mentioned in the Kojiki, Japan’s first history written in 710, and may be behind Japanese society’s emphasis on harmony and collectivism.

Shinto encourages a cheerful way of life and views life as about the pursuit of happiness rather than being constrained by dogmatic rules concerning “sin.” There is no concept of sin or salvation in Shinto. There is not even a belief in karma, like in Buddhism or Hinduism.

Shinto assumes the inherent goodness of nature and humanity. The essence of all life is a gift from kami, so it is flawless, even if humans err. Errors are actions, and those mistaken actions do not follow us around forever.

As from physical dirt, our spirits can be restored and cleansed from mistakes we’ve made through purification. Love and kindness help us to maintain that cleanness and to develop a clean and pure character.

Humans continue to grow throughout their lives and after their lives. Eventually, they may even become kami themselves.

Matsuri, or festivals

Matsuris are festivals and ceremonies by which the Japanese appease the sometimes violent kami of nature and pray for blessings. Some are religious matsuris, like those in the spring and fall, where Shinto priests represent the community and pray and give thanks for bountiful harvests.

Other matsuris serve as entertainment for the kami. During these festivals, the kami is carried through the town in a portable shrine and people dance in a procession in the streets. Sumo wrestling and Noh theater are other types of matsuris that are entertainment dedicated to kami.

Matsuris provide a way for communities to both connect to the kami and be strengthened and rejuvenated themselves.

Beauty and goodness are intertwined

Japanese aesthetics reveal an inherent love of beauty displayed through the use of clear clean lines, simple patterns, and subtlety of design. In a similar vein, moral behavior is associated with the balance of mind, body, and spirit.

Evil deeds and misfortunes are attributed to magatsubi, the curved spirit. Ugliness is associated with things warped and crooked, including our minds. Immoral behavior is rooted in spiritual or intellectual imbalance.

Part of Shinto’s ritual cleansing is to purify our thoughts and straighten our way of thinking.

Purity and cleanliness

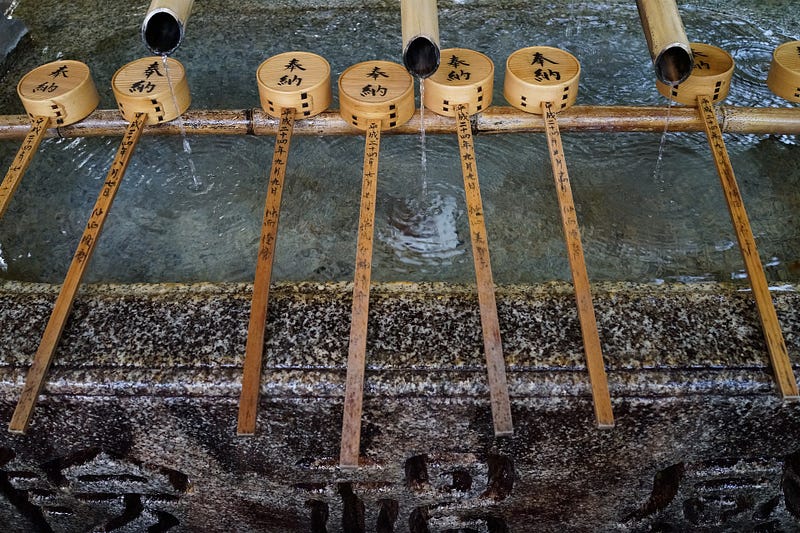

Before entering a shrine, visitors wash their hands and rinse their mouths with special water provided near the torii gate.

Shrines are always kept clean and pure. They are often surrounded by trees and filled with the divine energy of nature. They are places to worship, relax, and be refreshed and renewed.

Essential to Shinto is the practice of misogi, ritual cleansing of both body and spirit. In ancient days, washing in the salty water of the sea was believed to be the best way to be cleansed.

Today, the traditional importance of salt in Shinto purification can be seen when sumo wrestlers sprinkle salt in the sumo ring to purify it before a match, or in the piles of salt on either side of doors to prevent the entry of evil spirits.

Shide, or hakuhei, the white folded papers hanging from shimenawa ropes, purify those who pass by absorbing their negative energy. The shimenawa rope itself is said to attract and capture negativity and uncleanness. These provide a protective barrier at the gates of shrines, keeping the shrine and its grounds pure.

Mirrors

Mirrors in shrines are not the object of worship, but rather they reflect the radiant light of the spirit of kami. The mirror enshrined at the Ise Grand Shrine is of supreme importance and is one of Japan’s Three Sacred Treasures.

To understand those sacred treasures, we need to visit a couple of stories told in Japan’s most ancient history book, the Kojiki.

Amaterasu and the Cave

This story revolves around Amaterasu Omikami, the sun goddess, and her younger brother Susanoo no Mikoto, the god of the sea and storms. I will just call them Amaterasu and Susanoo.

Amaterasu was charged by her father with the job of ruling the Plain of Heaven and Susanoo with ruling the sea. But Susanoo, much like an errant teenager, had other ideas.

He ascended to the Plain of Heaven and wreaked havoc. He broke down the footpaths between Amaterasu’s rice fields, filled up the drainage ditches, and spread dung in the divine hall.

All this, his patient sister forgave.

But when Susanoo threw a flayed horse through the roof of Amaterasu’s house and killed her weaving maid, Amaterasu had had enough.

So what did this powerful sun goddess do?

She hid in a cave.

Naturally, when she entered the cave, the Plain of Heaven was engulfed in darkness. What could be done in this pitch blackness?

The kami met together and made a plan.

One group was charged with forging a mirror. Another with stringing beautiful magatama, comma-shaped gems. A third with uprooting a Sakaki tree. The kami hung the mirror and jewels on the tree and brought it near the mouth of the cave wherein Amaterasu had shut herself. A strong, muscular kami stood ready by the door of the cave.

The kami gathered before the cave and began to play music and cavort. Ame no Uzume no Mikoto began to dance. Her dance grew wilder and more audacious, and she started tearing off her clothes. The other kami laughed uproariously.

Amaterasu, inside the cave, could not believe her ears. She had plunged the world into darkness — what was funny about that?

Yielding to her curiosity, she opened the rock cave door a sliver. She said, “I am hiding in this cave, and your whole world is in darkness. What could possibly be funny?”

The kami answered, “We have a more powerful goddess than you now, Amaterasu!”

Just then, the strong kami tossed away the rock door and other kami held the mirror before Amaterasu’s face. When she came near to look more closely at that beautiful, powerful goddess, the strong kami pulled her outside, and a second kami strung a divine rope across the cave’s mouth, blocking her return — the first shimenawa rope.

Light returned to the world.

Susanoo was punished for his troublemaking and banished from the Plain of Heaven.

Susanoo and the 8-headed dragon

Back on earth, Susanoo came upon an old couple crying bitterly.

Answering Susanoo’s concern, the old man explained, “I had 8 daughters, but every year, the great dragon Yamata no Orochi comes and eats one of them. This is my last daughter, Kushinada Hime, and the dragon is on its way to take her now.” He wept again.

“What does this dragon look like?” asked Susanoo.

“It has 8 heads and 8 tails, eyes as red as winter cherries, and great trees grow from its back. Its belly is thoroughly stained with blood.”

Susanoo asked, “Will you give me your daughter?”

“But, wait. Who are you?” the startled man asked.

“I am the great Amaterasu Sun Goddess’s younger brother, Susanoo no Mikoto.”

The man willingly gave his last daughter to Susanoo. He was desperate to save her life.

Susanoo turned her into a comb (her name, Kushi, means comb), and stuck it into his long hair for safekeeping. Then he turned to the old couple and instructed them, “Distill alcohol to 8 times its strength and place a barrel of this strong drink on each of 8 platforms.”

This they did. Then, they waited.

Sure enough, the monstrous dragon appeared and thrust each of its heads into one of the barrels, slurping greedily. It then fell into a deep sleep, and Susanoo made quick work of its slaughter.

When he was cutting off one of its tails, his blade struck something hard. He peered inside and pulled out a marvelous sword.

Susanoo returned to his sister, Amaterasu, and presented her with this sword as a peace offering.

Sometime later, when Amaterasu sent her grandson, Ninigi no Mikoto, down to rule the earth, he carried with him the sword, the mirror that had been held before the face of Amaterasu in the mouth of the cave, and the brightest jewel that had decorated the mirror.

Those became the Three Imperial Treasures of Japan, symbolizing the three main Shinto deities — Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess; Tsukuyomi no Mikoto, the Moon God; and Susanoo, the God of the Sea and Storms.

Amaterasu’s mirror of wisdom is enshrined at the Great Ise Shrine. The sword of valor, called Kusanagi no Tsurugi, is at Atsuta Shrine in Nagoya. And the Yasakani no Magatama jewel of benevolence is preserved at the Imperial Palace in Tokyo.

Shrines

Today, there are over 80,000 Shinto shrines in Japan. I hope you each have an opportunity to visit one and take some time to bask in its peaceful atmosphere.

References:

The Kojiki; The Essence of Shinto, by Motohisa Yamakage; Soul of Japan, Public Affairs Headquarters for Shikinen-Sengu; Kumano Kodo Official Guide; visiting numerous shrines.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/