Giving thanks and offering prayers for children’s health, safety, and long life

Perhaps you’ve been lucky enough to catch a glimpse of a cute little girl dressed in a formal kimono walking with her parents at a Shinto shrine. Or maybe a little boy playfully running about in a men’s style hakama kimono.

These children have gone with their parents to their local shine to celebrate their Shichi-Go-San, continuing a tradition of offering thanks and prayers that started over 1,000 years ago.

Shichi-Go-San, 7–5–3

During the Heian Era (794–1185), the lucky, odd-numbered years of 3, 5, and 7 marked important milestones in a child’s life. To celebrate these auspicious occasions, children were dressed in their Sunday best and paid a visit to a Shinto Shrine or Buddhist temple.

Shichi-Go-San collectively refers to these events:

For both boys and girls at age 3 — 髪置き Kamioki

Parents had traditionally kept their little ones’ heads shaved. At age 3, children celebrate the age when this practice stops and they can start growing their hair.

For boys age 5 — 袴着 Hakamagi

At age 5, boys wear their first hakama, formal kimono trousers worn by adult men. On top of these, the child wears a long haori jacket. These clothes symbolize his entrance into society as a parishioner of his local shrine or temple.

For girls age 7 — 帯解 Obitoki

At age 7, girls wear their first stiff kimono obi sash, just like adult women. Until then, they wear a sort of soft, padded vest over the top of their kimono called a hifu, 被布. These beautifully decorated vests are worn to cover the soft sash or narrow belt with which the kimono was tied in lieu of an obi.

As the centuries passed, the Shichi-Go-San customs spread down to the common people. Part of this celebration marked the child’s transition from the more dangerous stage of infancy — child mortality rates were high — to the more secure stage of childhood. Parents expressed gratitude and offered prayers for their child’s continued health, safety, and longevity.

Shinto ceremony

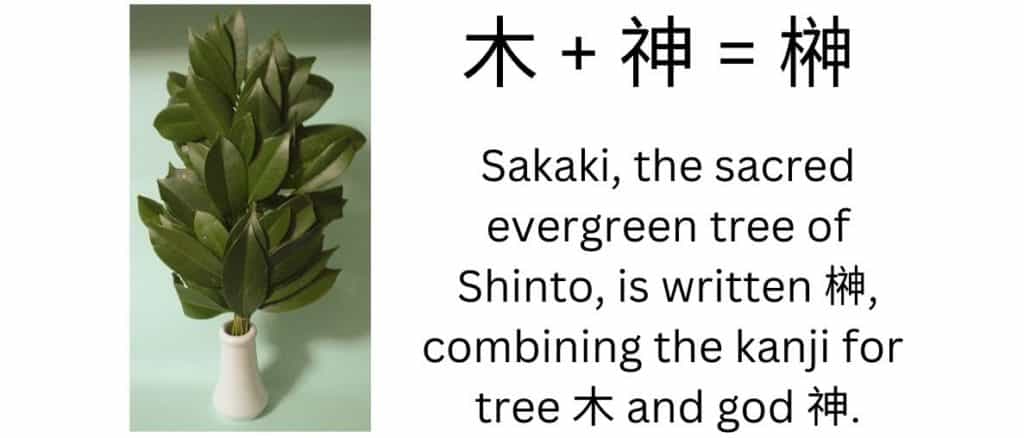

When the parents and their child arrive at the shrine, they traditionally offer a Sakaki branch decorated with paper strips called a tamagushi, 玉串. Sakaki has long been considered a type of lightning rod that invokes the spirit of Kami, the Shinto god. Offering a sacred Sakaki branch shows respect to the deity and transmits the prayers of the believers.

The priest then purifies the family by removing their sin, uncleanness, and misfortune by using a stick or Sakaki branch tied with linen or paper streamers which he waves left, right, and left over the family.

He then reads aloud the names of the children present, after which each child presents a tamagushi at the altar.

The ceremony ends with a traditional kagura dance performed by one of the shrine maidens, or miko, 巫女. Then the children receive gifts.

Children’s gifts

Parents give special gifts to their children on Shichi-Go-San.

Hamaya 破魔矢

Hamaya are good-luck arrows that attract happiness and ward off misfortunes. These are also popular gifts at New Year and on Children’s Day, celebrated on May 5th.

Omamori お守り

Omamori are small amulets sold at all shrines and many temples that invoke various benefits, such as good health, protection, success in studies, etc.

Chitose ame 千歳飴

Chitose ame, 1,000 year candy, originated at the Kanda Shrine in Tokyo and has since spread all over the country. On Shichi-Go-San, children are given gift bags of chitose ame, or 1,000-year candy. This long, thin candy is traditionally red and white, considered celebratory colors in Japan.

The child receives the same number of candies as his age. This gift symbolizes the parents’ wish for health, prosperity, and long life for their child.

Chitose ame are presented to the child in elaborately decorated bags with designs featuring cranes and turtles — symbols of long life; or pine, bamboo, and plum trees — symbols of steadfastness, perseverance, and resilience.

When Shichi-Go-San is celebrated

For centuries, people in Japan used the traditional method of counting age for celebrating Shichi-Go-San. In that method, a child is one year old upon birth and then a year is added to that age on each New Year’s Day. Although some families still use that reckoning when celebrating Shichi-Go-San, generally people use the modern method of determining age.

The official date for Shichi-go-san was set during the Edo era (1603–1867), as the 15th day of the 11th month. This date was chosen, it is said, because it was the day when the 5th Tokugawa shogun, Tsunayoshi, made offerings for his child, Tokumatsu. When the Gregorian calendar was adopted during the Meiji Era (1868–1912), the official name and date for Shichi-Go-San were determined. Nevertheless, parents are free to celebrate Shichi-Go-San at their convenience, generally sometime in mid-November.

Photoshoot

Celebrating Shichi-Go-San makes for a great photo opportunity, and many families visit photo studios to have their pictures taken in their formal attire to commemorate their child’s Shichi-Go-San.

As you would expect, the day ends with a celebratory meal together.

One of the beauties of Shinto is how its ceremonies mark the passage of time. Not only throughout the year with planting and harvest festivals, but with milestone reminders in individuals’ lives, like Shichi-Go-San.

References:

Encyclopedia of Shinto, The Essence of Shinto, 七五三, 民俗探訪事典.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/