From the creation of Honshu to Magatama jewels

On the far western edge of Niigata Prefecture sits the quiet city of Itoigawa. With a population of just over 40,000, it’s hard to believe it was once the bustling center of a thriving jade trade. That trade has long since vanished, yet diligent beachcombers can still find jade pieces along Itoigawa’s pebble shores.

The same tectonic upheavals that separated Japan from the Asian mainland, created the Fossa Magna, and uplifted the Japanese Alps also brought jade to the surface at Itoigawa from where it had been formed deep within the bowels of the earth 500 million years ago.

Before we get into the jade, let me explain a bit about the geology of Japan.

The Fossa Magna

Among the many Western advisors and teachers invited to Japan to assist in its modernization during the Meiji period (1868–1912) was the German geologist Heinrich Edmund Naumann.

In addition to his teaching position at Kaisei Gakkō, the forerunner to Tokyo Imperial University, Naumann set out to create a geological map of Japan. With train travel in its infancy, Naumann carried out his surveys on foot or horseback, traveling over 10,000 kilometers in his quest to draw an accurate topographical map.

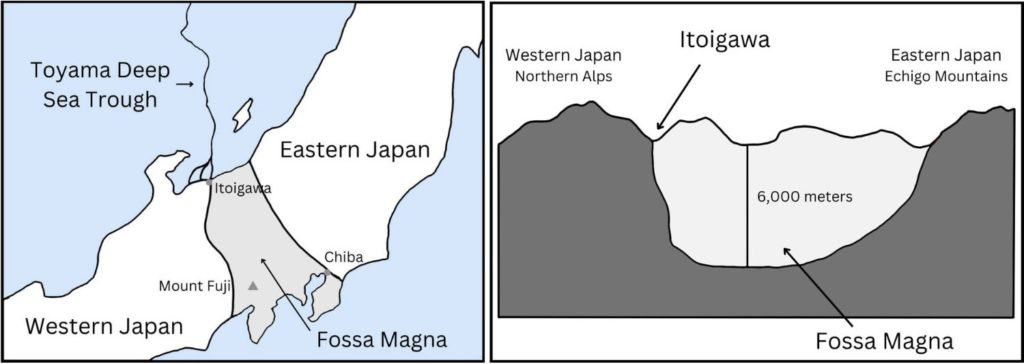

During his explorations, Naumann’s observations of a low-lying crevasse that divides the Echigo Mountains from the Northern Alps led to his discovery of a wide rift that bisects the island of Honshu, dividing it between its eastern and western halves. He named this rift the Fossa Magna, Latin for “Great Crevasse.”

The Fossa Magna is a U-shaped rift, 6,000 meters deep, situated between two major fault lines. On the western side lies the Itoigawa-Shizuoka Tectonic line, running north to south and roughly following the course of the Himekawa River. The eastern side is marked by the Tanakura Tectonic Line. The Median Tectonic Line, the longest fault line in Japan that runs the length of Honshu, crosses the Fossa Magna in its center.

About 19–15 million years ago, the movement of tectonic plates resulted in significant geological upheavals in East Asia. The Philippine plate subducted beneath the Eurasian plate, while the Pacific plate subducted beneath the North American plate. These events caused the breaking off of a land mass from the southern coast of the Eurasian continent.

As the land separated, the western section rotated clockwise by 40–50 degrees, and the eastern section rotated 40–50 degrees counterclockwise, forming the bent shape of what would become Honshu Island. The gap that opened between these halves formed the Fossa Magna. The region separating the land masses and the continent eventually evolved into the Sea of Japan.

Over time, the depression that would become the Sea of Japan gradually filled with water, initially forming a freshwater lake, as evidenced by fossils of freshwater fish and insects. Eventually, the lake expanded and connected with the ocean, transforming into the Sea of Japan.

Seawater also rushed into the Fossa Magna, creating the Fossa Magna Straight. Today, fossils of herring, sea bass, and even whales can be found in the Fossa Magna. Subsequent earthquakes triggered volcanic eruptions and underwater landslides, depositing alternating layers of sandstone and mudstone on the bed of the Fossa Magna Strait, gradually filling it and displacing the seawater.

Approximately 3 million years ago, the North American and the Eurasian plates collided along the Itoigawa-Shizuoka Tectonic line, uniting the land masses into the island of Honshu and uplifting the Japanese Alps. The junction where these two plates meet forms the western boundary of the Fossa Magna.

Around 1 million years ago, magma pushing up through the Fossa Magna erupted and, over time, shaped the volcanoes we see today — Mount Fuji, Mount Yatsugatake, Mount Yakeyama, and others.

Despite the presence of these and many other volcanoes, over half of all the mountains in Japan — that cover a staggering 73% of the country — are primarily composed of sedimentary rather than volcanic rock.

As plates collided and subducted, coral reefs and seafloor sediment were uplifted onto the continental edge. The results of this upheaval are easily seen today in the fossil-rich limestone deposits and seashells that grace mountaintops and plateaus across Honshu, from the Akiyoshidai plateau of Yamaguchi to the 1,188-meter-high Mount Myojo in Itoigawa.

The geological processes that shaped Japan’s magnificent landscape also played a pivotal role in the development of the world’s oldest Jade culture, centered in the small coastal city of Itoigawa.

Itoigawa’s Jade

Jade, most often associated with its green color, is actually white in its pure form. The vibrant and varied hues of jade — green, lavender, blue, and black — result from impurities present in the mineral. Brilliant green jade gets its color from iron and chrome impurities, while titanium and manganese create a light purple color known as lavender jade. The combination of iron and titanium gives jade a rich blue shade. This wide range of colors adds to the allure of this durable gemstone.

A poem recorded in the Manyoshu, Collection of Ten Thousand Leaves, the oldest anthology in Japan, refers to jade stones from Itoigawa. This historical mention was all but forgotten until 1939 when jade was found beneath the clear waters of the Kotaki River in Itoigawa.

Archeologists have since discovered jade artifacts from Itoigawa all across Japan, indicating a widespread trade network that flourished from 1,500 BC through the 5th century. Ancient people likely traveled along the coasts in their dugout canoes, engaging in trade that included jade from Itoigawa, obsidian from northwestern Kyushu, shells and shell accessories from the Ryukyu Islands, and other goods.

Itoigawa jade artifacts have been found in graves and settlement sites from Hokkaido in the northeast to the distant islands of Okinawa in the southwest. Itoigawa jade has even been found on the Korean peninsula, carried by intrepid traders navigating their dugout canoes on the sea between Kyushu and Korea.

The archaeological discoveries in Itoigawa and throughout Japan and Korea have yielded various jade artifacts, including beads for necklaces and bracelets, pendants, comma-shaped magatama, raw stones, and numerous fragments. Many of these jade pieces exhibit shallow indentations instead of holes. This variation in craftsmanship reflects the different techniques artisans used in each area.

In Itoigawa, artisans used quartz sand to drill holes in the jade, skillfully working with the hard material. On the other hand, artisans in the southern islands attempted to apply the same methods they used for working with the much softer substance of shells. Their not-so-skillful efforts resulted in frequent breakage and incomplete jade pieces.

Although jade was much sought-after for centuries, by the mid-500s AD, a change occurred in Japanese fashion trends. Accessorizing with jewelry created from exotic shells from Ryukyu and prized jade from Itoigawa declined in popularity. In its place, perhaps influenced by the influx of knowledge and technology from China, a new preference emerged for the continental style of wearing gilt bronze bracelets and necklaces.

Interestingly, no accessories at all have been found in graves or excavations from the 8th century onwards, suggesting that the wealthy turned their attention to elaborate kimonos rather than jewelry. However, beads continued to adorn Buddhist statues, particularly those of Kannon, the bodhisattva of mercy.

Among all the jade jewelry worn in ancient times, though, comma-shaped magatama beads and pendants seem to have been especially prized. One such magatama, the Yasakani no Magatama, is counted among Japan’s Three Imperial Treasures, alongside the Kusanagi no Tsurugi sword and the most precious, Yata no Kagami mirror.

To understand these sacred treasures and their importance to Japanese history and culture, I invite you to read this story from Japan’s most ancient chronicle, the Kojiki.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/