Mentor to Japan’s Meiji Restoration leaders

Hagi

The quietness of the fishing town of Hagi, in southwest Honshu, belies its illustrious past. Hagi is the birthplace of many of the men who laid the foundations for modern Japan and the location of the school that formed their ideas. Their teacher was Yoshida Shōin, and his brief but impactful life is inextricably tied to Hagi and his school, Shōka Sonjuku, The School Under the Pines. Among Yoshida’s students were greats of the Meiji government, including the military reformer Takasugi Shinsaku and Itō Hirobumi, Japan’s first prime minister.

Built on a delta opening to the Sea of Japan, Hagi’s locale has made it an ideal home for fishermen for millennia. Records dating from the Muromachi period (1336–1573) tell of the Yoshimi, retainers of the Ōuchi clan, building the first small fort in Hagi. Despite its early origins, the town remained quiet and secluded until the start of the Edo era (1603-1867).

Today, Hagi has been left behind in much of the modernization of Japan. An hour from the nearest airport or Shinkansen station, Hagi is a town of 42,000 residents, with a steady population decline of 1,000 annually for the past 15 years. Walking its quiet streets, one sees fishermen plying their nets and shops grilling freshly caught squid, occupations that have changed little since the days Yoshida Shōin walked these same streets.

Historical Overview

The 15th and 16th centuries, known as the Warring States Period, were marked by unprecedented internal strife. Daimyō, feudal lords, fiercely fought for power and territory, plunging the nation into anarchy. In 1543, Portuguese sailors stepped foot on a southern Japanese island, introducing guns to the country for the first time. Soon thereafter, the great warlord, Oda Nobunaga, using Portuguese matchlock shotguns, subdued one domain after another. Over 20 years, he succeeded in uniting much of the country—until he was betrayed by one of his own and driven to commit seppuku, the samurai’s ritual suicide.

One of Nobunaga’s generals, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, consolidated power and continued the work of unification by force. Before he succumbed to illness in 1598, he set up a Council of Five Elders to govern Japan until his five-year-old son was fit to rule. One of those elders was Tokugawa Ieyasu, a shrewd and intelligent warlord, to whom Hideyoshi had granted the backwater castle town of Edo (now Tokyo).

Hideyoshi’s death led to a power struggle among the Council members, culminating in the decisive Battle of Sekigahara in 1600. Western daimyō, led by Ishida Mitsunari, clashed with eastern daimyō, led by Ieyasu. After a brief but bloody battle, Ieyasu emerged victorious. In 1603, Emperor Go-Yozei appointed Ieyasu as shogun, inaugurating the Tokugawa shogunate and the Edo era.

The Mori clan and the Edo era (1603-1867)

During the late 16th century, daimyō Mōri Terumoto commanded Japan’s finest navy and ruled over a domain encompassing all of western Honshu and part of northern Kyushu. Although not personally involved in the Battle of Sekigahara, he was aligned with the losing side. As a consequence, when Tokugawa Ieyasu became shogun, he ordered Terumoto’s territory to be reduced by two-thirds, leaving him with only the Chōshū domain. Ieyasu banished Terumoto to isolated Hagi, far from the Sanyodo highway that roughly followed the shore of southeastern Honshu and provided access to Kyoto and Edo.

Mōri Terumoto made Hagi his capital, choosing Mount Shigetsu, a tied island connected to the mainland by a sandbank, as the site for his castle. Perched atop the 150-meter (492-foot) hill, the five-story castle commanded a magnificent view of the town and the surrounding sea. The sea acted as a natural moat on three sides, one of just a handful of Japanese castles to use this defensive feature. The Mōri clan ruled the Chōshū domain from luxurious residences in their castle compound for over 250 years during the Edo era.

During those years, Japan was all but closed to outside influence. From 1636, Japanese were prohibited from leaving the country. If they dared break that law, the penalty upon return was death. The Dutch were the only Westerners permitted to engage in tightly controlled trade, and they were confined to the tiny man-made island of Dejima in Nagasaki on the southern island of Kyushu. During this period of seclusion, the Tokugawa shoguns’ stringent rule enabled the country to flourish. Rice production increased, the literacy rate rose, and culture blossomed. Woodblock prints, kabuki, tea ceremony, and martial arts developed and became more refined.

Only those of the samurai class were permitted to carry weapons. These regal samurai were easily distinguished by their chonmage topknots and two swords—one short, one long. Young samurai attended schools where they studied strict Confucian principles of duty and filial piety, martial arts, and poetry composition.

Yet, as the decades of this self-imposed isolation passed, a desire and curiosity about the world beyond their border began to grow. In 1720, the 8th shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune, eased the prohibition on the import and translation of foreign books. This led to the emergence of rangaku, or Dutch studies, where small pockets of scholars immersed themselves in these newly imported Dutch books. Guided by the slogan, “Eastern ethics with Western science,” these men absorbed knowledge of Western medicine, mathematics, and military science.

When Yoshida Shōin was born in 1830, Japan had been closed for 200 years. Rangaku intellectuals had influenced the scholarly samurai, who were coming to understand that more than their martial spirits and Confucian ethics were necessary for Japan to walk on equal footing with Western nations.

Yoshida Shoin

Yoshida Shōin, born Sugi Toranosuke, came from a low-ranking samurai family in Hagi. At the age of four, he was adopted by the Yoshida clan, renowned for providing military instructors to the daimyō. Shōin was educated in military arts at the Meirinkan domain school in Hagi and later in Edo.

During the Tokugawa era, strict regulations governed travel, requiring individuals to obtain permission and official permits to journey beyond their clan’s territories. Violation of these rules could result in death. Nevertheless, when Yoshida Shōin returned to Hagi after his studies in Edo, he felt compelled to explore northeastern Japan. At the end of 1851, Shōin took the daring step of leaving the Chōshū domain without permission to travel throughout the country. This act of rebellion against his lord branded him a rōnin, or masterless samurai.

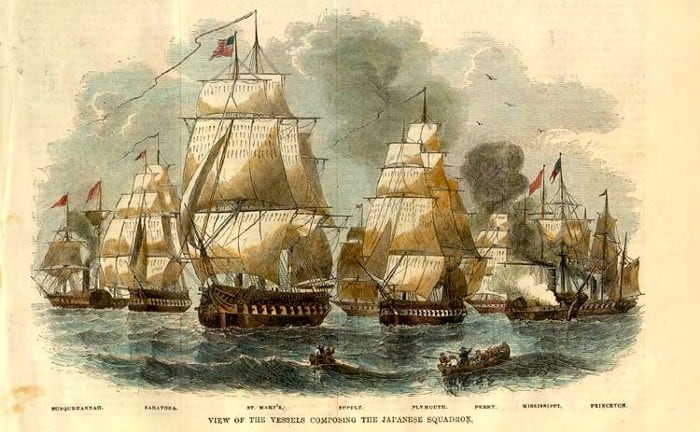

Upon his return to Hagi, Yoshida Shōin was spared from execution, as Chōshū was perhaps the most lenient domain towards rōnin. However, Shōin was stripped of his samurai status and financial stipend and put under the guardianship of his father. Then, in a curious twist, he was granted the freedom to travel and study wherever he pleased for a decade. The following year, he again journeyed to Edo, arriving just in time to witness US Navy Commodore Matthew Perry’s menacing black ships enter Edo harbor.

Yoshida Shōin saw firsthand the impending crisis confronting Japan. No longer could the country cling to its feudal ways when faced with the formidable military prowess of foreign powers at its gates. Japan’s desperate need for Western technology was crystal clear. The weak and ineffectual shogunate must be overthrown to pave the way for change. It was time for Yoshida Shōin to take a second daring step. He wanted—needed—to see the West.

Approaching Commodore Perry

While two of Commodore Perry’s officers were ashore one evening, they noticed a couple of well-dressed Japanese men following them. These men were Yoshida Shoin and his companion, Kaneko Shigenosuke.

Commodore Perry describes this event in his book, Narrative of the Expedition of an American Squadron to the China Seas and Japan, 1857.

Perry wrote,

The Japanese were observed to be men of some position and rank, as each wore the two swords characteristic of distinction, and were dressed in wide but short trousers of rich silk brocade. Their manners showed the usual courtly refinement of the better classes, but … they cast their eyes stealthily about, as if to assure themselves that none of their countrymen were at hand to observe their proceedings, and then, approaching one of the officers and pretending to admire his watch-chain, slipped within the breast of his coat a folded paper. They now significantly, with the finger upon the lips, entreated secrecy and rapidly made off.

The folded paper turned out to be a letter, written with the utmost respect and politeness. It read, in part:

Two scholars from Yedo, in Japan, present this letter for the inspection of the high officers and those who manage affairs. Our attainments are few and trifling, as we ourselves are small and unimportant, so that we are abashed in coming before you… We have, however, read in books, and learned a little by hearsay, what are the customs and education in Europe and America, and we have been for many years desirous of going over the five great continents, but the laws of our country in all maritime points are very strict…

We now secretly send you this private request, that you will take us onboard your ships as they go out to sea; we can thus visit around in the five great continents, even if we do, in this, slight the prohibitions of our own country… If this matter should become known, we should uselessly see ourselves pursued and brought back for immediate execution without fail.

That night, Yoshida Shoin and his companion got into a small boat and made their way to Perry’s ship. Perry’s description of the event continues,

Having reached [our ship] with some difficulty… They frankly confessed that their object was to be taken to the United States… They were educated men and wrote Mandarin Chinese with fluency and apparent elegance, and their manners were courteous and highly refined. The Commodore, on learning the purpose of their visit, sent word that he regretted that he was unable to receive them, as he would like very much to take some Japanese to America with him. He, however, was compelled to refuse them until they received permission from their government, for seeking which they would have ample opportunity, as the squadron would remain in the harbor of Shimoda for some time longer.

They were greatly disturbed by this answer of the Commodore and, declaring that if they returned to the land, they would lose their heads, earnestly implored to be allowed to remain. The prayer was firmly but kindly refused. A long discussion ensued, in the course of which they urged every possible argument in their favor and continued to appeal to the humanity of the Americans. A boat was now lowered, and after some mild resistance on their part to being sent off, they descended the gangway piteously deploring their fate.

Perry well knew that the men would be considered criminals under Japanese law. However, since this incident occurred immediately after Japan had been coerced into signing the treaty that opened the country, Perry was cautious about jeopardizing diplomatic relations by knowingly violating local laws.

When Shōin and Shigenosuke reached shore, they were promptly arrested and jailed. Ever the scholar, Shōin engaged with his fellow prisoners, identifying each man’s talents and enlisting them as instructors. One man taught Chinese philosophy, and another taught poetry. The respect shown to these prisoners by Shōin not only restored their pride but transformed the atmosphere in the prison. Before long, Shōin was able to arrange the release of many of the detainees.

Shoka Sonjuku—“The School Under the Pines”

When Yoshida Shōin was released from jail, he took over his uncle’s small school in Hagi, the Shōka Sonjuku. He welcomed anyone who wanted to learn, regardless of status or class. After his imprisonment, Shōin was no longer free to travel, so he sent his students around the country to be his eyes and ears, while he put brush to paper and wrote extensive essays.

During these years, samurai and rōnin united in opposition to Commodore Perry’s gunboat diplomacy that forced Japan to open its doors. Their call to arms spread through the country, Sonnō-jōi, “Revere the emperor, expel the barbarians!” Yoshida’s Shōka Sonjuku became the heart and soul of this movement.

In addition to their scholarly studies, Shōin’s students and local farmers trained in close-order drills, using sticks as makeshift rifles. Under his influence, most of the 80 students he taught in his less than three years at that school later threw themselves into loyalist activities.

Ii Naosuke becomes Tairo

In 1858, Ii (pronounced EE) Naosuke, the daimyō of Hikone, was made Tairō, honorary chief councilor, making him the most powerful man in the country after the shogun. Meanwhile, in Shimoda, 134 kilometers (83 miles) south of Edo, the American diplomat Townsend Harris was pressuring the shogunate to ratify the Treaty of Amity and Commerce. Despite lacking the emperor’s authorization, Naosuke ordered this to be signed. Commonly referred to as the Harris Treaty, it imposed unfavorable exchange rates, deprived Japan of autonomy in setting tariffs, permitted the unrestricted free export of Japanese gold and silver, and granted foreigners exemption from Japanese law.

Soon, Naosuke negotiated similar unequal treaties with the Dutch, the Russians, the British, and the French. Many sonnō-jōi activists fiercely opposed the autocratic reign of Ii Naosuke as Tairō and saw these treaties as a severe compromise of Japan’s sovereignty. Rōnin and samurai across the country voiced their criticism and resorted to attacking shogunate officials and Westerners in protest.

In response, Naosuke fought back with the full force of his power against those who did not support his authority and foreign trade policies in what came to be called the Ansei Purge. Those who dared oppose him were subjected to imprisonment, torture, exile, or execution.

The first person Naosuke arrested was Umeda Unpin, a leader of the sonno-joi movement from Obama in present-day Fukui Prefecture. Unpin was taken from his home in Kyoto, caged, and carried to Edo. In Hagi, Yoshida Shōin’s plans and ideas to overthrow the shogunate had been deemed dangerous by the Chōshū government, which led to his imprisonment. Unpin’s interrogators in Edo learned he had spent time in Hagi meeting with Shōin, and because of this, Shōin soon found himself confined in a cage and brought to Edo.

Leaving his beloved Hagi and passing along the portion of the Hagi Okan known as the Namida-Matsu, Pines of Tears, he composed a poem.

Certain, as I am, there shall be no return from this journey,

All the more do my tears wet this teary pine.

In prison in Edo, Yoshida Shōin was questioned about his discussions with Unpin. Seeing this as a good opportunity to voice his opinions on the shogunate, Shōin openly admitted his plan to assassinate Manabe Akikatsu, Ii Naosuke’s right-hand man. This confession sealed his fate. On November 21, 1859, at the age of 29, after politely thanking the prison attendant, Yoshida Shōin met his end with quiet dignity as the executioner’s blade fell.

Naosuke’s Ansei Purge killed not only Yoshida Shōin but over 100 other influential figures. In its aftermath, elements seeking revenge, particularly radicals from Chōshū and sympathizers of the victims, launched widespread acts of terrorism. In 1860, as he passed through the Sakurada-mon gate of Edo Castle, Naosuke was assassinated by a band of samurai and rōnin from the Mito domain.

Movement to Overthrow the Shogunate

In the following years, radical reformist activists emerged who pledged allegiance to the emperor. These shishi, or loyalists, sought to resist external pressure from foreign powers and to overturn the existing political system. Their sonnō jōi cause, although still “revering the emperor,” adopted a new goal—tōbaku, “overthrow the shogunate.” This idea again united samurai and rōnin, and Yoshida Shōin was adopted as their spiritual leader and martyr for their cause.

Within a decade of Shōin’s untimely death, many of his students became key figures in the tōbaku movement. One disciple, Takasugi Shinsaku, created an entirely new army. For centuries, Japan’s military class had been composed exclusively of samurai. Shinsaku turned this on its head by forming an army that included farmers, tradesmen, merchants, priests, and even sumo wrestlers.

Using surplus weapons from the American Civil War purchased through the Scottish merchant, Thomas Blake Glover in Nagasaki, Shinsaku’s Chōshū troops marched shoulder to shoulder with the samurai of Satsuma (Kagoshima) in a united front against the shogun. After several years, their combined forces successfully toppled the Tokugawa shogunate and restored power to the emperor in the Meiji Restoration of 1867.

Civilization and Enlightenment—the Meiji government

Top, right to left: Minister of Foreign Affairs Inoue Kaoru (From Hagi), Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi (From Hagi), Army Chief Arisugawa Taruhito (From Kyoto), Minister of the Court Sanjō Sanetomi (From Kyoto), Minister of Navy Admiral Saigō Jūdō (From Satsuma, later Kagoshima), and Minister of Agriculture and Commerce Lieutenant General Tani Tateki (From Tosa, later Kochi).

Middle, right to left: Minister of Justice Yamada Akiyoshi (From Hagi), and Minister of Communications and Transportation Enomoto Takeaki (From Edo, later Tokyo).

Bottom, right to left: Home Minister Yamagata Aritomo (From Hagi), Minister of War Admiral Ōyama Iwao (From Satsuma, later Kagoshima), Minister of the Interior Matsukata Masayoshi (From Satsuma, later Kagoshima), and Minister of Education Mori Arinori (From Satsuma, Later Kagoshima).

Woodblock print by Hashimoto Chikanobu. (Public Domain)

Just months after the last shogun returned power to Emperor Meiji, the Boshin Civil War erupted between samurai loyal to the Tokugawa shogunate and the New Government’s Imperial forces. In June 1869, the government emerged victorious, and the process of nation-building began.

During the early Meiji era (1868-1912), a wave of modernization swept the country. Japan made significant advancements by enlisting Western advisers to aid in every aspect of its development. This period saw the introduction of compulsory education, the establishment of railroads and telegraphs, the development of textile mills, and the acquisition of mining equipment. A Western system of civil and criminal laws and a Western-style constitution transformed Japan into a constitutional monarchy.

Feudalism became a relic of the past. Castles were dismantled. Samurai cut off their topknots and gave up their swords. The class structure that kept the samurai at the top was done away with. In their fervor for “civilization and enlightenment,” the Japanese set their sights on industrialization and colonization, achieving unprecedented results in a few short decades.

Many of the surviving students of Yoshida’s Sonjuku school went on to hold prominent positions within the new government.

- Ito Hirobumi became the country’s first prime minister in 1885. He helped author the Meiji Constitution, was Home Minister, the first Resident-General of the Japanese Protectorate of Korea, and the prime minister on three more occasions.

- Kido Takayoshi was responsible for educating young Emperor Meiji, helped draft the Five Charter Oath, and was an advocate for the new constitution.

- Inoue Kaoru held many positions in the Meiji government—Vice Minister of Finance, Japan’s first Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Agriculture and Commerce, Home Minister, and more.

- Yamagata Aritomo shaped Japan’s modern conscription army, held top positions in the military, was Japan’s third prime minister, and was twice President of the Privy Council.

Emperor Meiji described the philosophy of this new era,

May our country,

Taking what is good,

And rejecting what is bad,

Be not inferior to any other.

By the time Emperor Meiji reached his sixth decade, Japan had established itself on the world stage. In 1905, British-educated Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō led his country to victory in the Russo-Japanese War, showing Japan to “be not inferior to any other.”

Although Yoshida Shōin did not live to see the remarkable changes in his country, his legacy lived on through his illustrious students and the forward-thinking government they created.

In 1975, twenty-one years after the first Shinkansen plied the rails between Tokyo and Osaka, the San’yo Shinkansen tracks were built through Yamaguchi Prefecture, far to the east of the fishing town of Hagi, the quiet home of Yoshida Shōin’s grave. His former school, the Shōka Sonjuku, is now a museum to his memory.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/