An ancient practice on the verge of extinction

For millennia, strong women along the coasts of Japan have lived off the bounty of the sea — which they gathered from the sea floor by hand. These women are called ama.

Ama, 海女 or “sea women,” engage in the ancient practice of freediving. Sans air tanks, these women forage on the ocean floor and among reefs for sea creatures and seaweed. This tradition has endured for 3,000–5,000 years, tracing its origins to the hunter-gatherers of the Jomon Period. Unlike their ancestors, modern-day ama wear wetsuits, fins, and goggles, but the fundamental diving techniques remain unchanged.

Ama divers descend to depths of 20 meters (60 feet) in frigid water. They remain submerged for up to two minutes at a time, during which they search out and gather sea cucumbers, seaweed, abalone, and other shellfish. An experienced ama can collect as many as ten sea urchins in a single dive.

When they come up for air between dives, an ama’s forceful exhalations make a high-pitched sound called isobue, meaning sea whistle. This type of exhaling is said to cleanse their lungs of carbon dioxide to make room for the deep intake of breath they need for their next dive.

Ama divers have traditionally been women, and one suggested reason for this is that females’ subcutaneous fat layer helps them withstand prolonged periods in cold water. Fat layer or no, gathering shellfish and seaweed in freezing water without breathing equipment is challenging, yet this occupation has endured for generations. Girls learn the needed skills from their mothers to improve lung capacity, read ocean currents, and spot prime locations for high-quality shellfish.

These robust women continue to dive well into old age, with a substantial proportion of ama divers being elderly — some over 90 years old. These women love their work, are devoted to the craft, and have spent a major part of their lives in the sea.

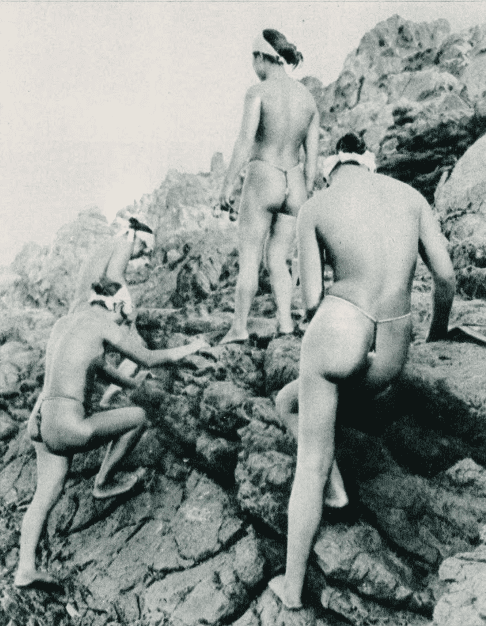

Until the introduction of Western thought in the Meiji Period (1868–1912), the traditional bathing costume for women was a loincloth. As such, when ama went into the sea, they wore only loincloths and tied on a headscarf adorned with charms invoking the protection of the gods. The use of goggles was introduced at the dawn of the 20th century.

During Mikimoto Kokichi’s pioneering experiments that led to the development of the first cultured pearls in the 1890s, he hired ama divers to collect oysters. As the years passed and his success and renown grew, Mikimoto arranged for his ama to give diving demonstrations for the visitors who flocked to see his oyster farm.

Noting the astonishment of foreign spectators at the scanty attire of the ama, Mikimoto devised what has become recognized as the “traditional” ama diving costume — shorts, a long-sleeved shirt, and a bonnet. To this day, the ama employed by Mikimoto wear this all-white amagi, fashioned over a century ago, as they perform pearl diving exhibitions at the Mikimoto Pearl Museum in Mie Prefecture.

Northernmost Ama

Like their sisters to the south, the northernmost ama divers of Kuji along the blustery Iwate coast used to wear a simple loincloth as they swam in waters that never exceeded 20°C (68°F). When they began to draw attention in the 1950s, they adopted their current costume — kasuri hanten (short jackets decorated with a splash pattern), along with a red obi belt, goggles, and a headscarf.

Kuji’s offshore area is one of the world’s foremost fishing grounds and is blessed with abundant high-quality seaweed. This treasure trove of urchins, abalone, and other premium seafood has been an excellent fishing ground for ama divers for centuries.

A popular 2013 NHK drama, “Ama-chan,” plunged the northernmost ama into the national spotlight by recounting the story of a beautiful young woman who traveled to Kuji to become an ama diver. However, as the years passed, the ama of Kuji have transitioned from their traditional work of gathering shellfish to becoming, well, tourist attractions.

As of 2010, based on the most recent survey conducted by Mie Prefecture’s Toba Sea-Folk Museum, there were 2,160 ama divers in Japan. This number starkly contrasts with the 9,100 reported in 1978 and the staggering 20,000 ama documented in the 1950s.

The decline in numbers persists. The enthusiasm among young women to continue the tradition of ama diving is waning. These girls have grown up observing their mothers and grandmothers engaged in diving, which, through youthful eyes, appears arduous. And perhaps it is.

Nonetheless, according to a seasoned ama, “There is hardship, but the strongest feeling I experience underwater is pure joy. The exhilarating rush I get when I find a large abalone is incomparable. I want to continue diving until the day I die.”

Would you like to try ama freediving?

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/