But should he be?

Ashikaga Takauji, 足利尊氏, was the first shogun of the Muromachi Period (1336-1573), and along with the monk Dōkyō and Taira no Masakado, one of Japan’s Three Great Villains. I have written about Dōkyō as the First Great Villain, and Masakado in my series on Japan’s Three Great Vengeful Ghosts. Now, we’ll take a look at Takauji.

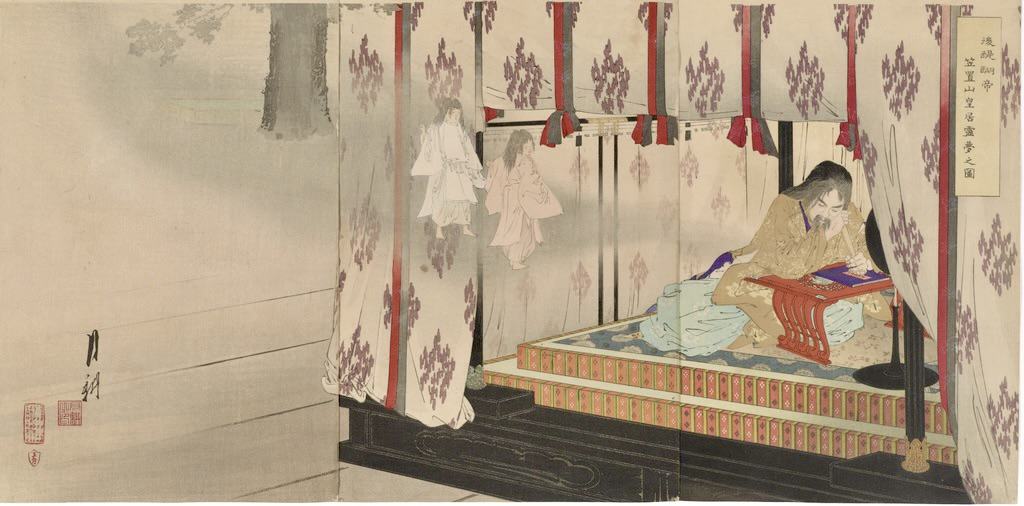

Great Villain #2 — Shogun Ashikaga Takauji

Takauji was instrumental in helping Emperor Go-Daigo overthrow the Kamakura Shogunate and restore power to the imperial house. Later, he — along with samurai throughout the country — became disillusioned by the emperor’s cronyism and extravagance. He forced Go-Daigo out of Kyoto, enthroned Emperor Kōmyō, and was named the first shogun of what came to be called the Muromachi Period.

But before I get ahead of myself, let’s go back in time a bit.

Background

In the late 13th century, Kublai Khan’s Mongol army invaded Japan. These incursions were thwarted not so much by the samurai who fought against the foreign barbarians, but by the “divine wind,” kamikaze, of two typhoons that destroyed the Mongol armada.

After battles, it had long been the custom for samurai to be rewarded with the wealth and lands of the conquered. As no lands had been conquered during the wars with the Mongols, none was given. The samurai who had risked their lives for their country were vexed.

Some years later, regent Hōjō Sadatoki, the ruler in Kamakura, issued an order forgiving the debts of those who had fought and returning confiscated lands to their original owners. This well-intentioned decree did not bring the hoped-for results. He ended up with dissatisfied samurai, a damaged economy, and serious disaffection with the Kamakura regime.

In 1331, Emperor Go-Daigo decided the time was ripe for a return to imperial rule. His armies attacked the shogunate forces in southern Kyoto. Hōjō Takatoki sent his trusted general, Ashikaga Takauji, to fight the imperial troops.

Although in mourning for his father who had just died, the loyal Takauji obeyed his lord and went to face the emperor’s army. He was victorious, although one can only imagine his resentment at abandoning his mourning to fight for the Hōjō.

As a result of this defeat, Go-Daigo was captured and banished to the Oki Islands, off the coast of what is now Shimane Prefecture.

In his absence, his son, Prince Morinaga, continued fighting, along with his storied general, Kusunoki Masashige, famed for holding his own against much larger armies and inflicting heavy casualties on the Hōjō forces.

In 1333, Go-Daigo escaped from Oki in the dark of night with the help of a fisherman. When word got out, many generals rallied to his cause. This encouraged Go-Daigo to issue an edict to overthrow the powerful Hōjō family. A full-out war ensued.

Again, Hōjō Takatoki sent Takauji to defeat the imperial forces in Kyoto. Upon reaching the city, Takauji, knowing the way the wind was blowing, switched sides. Instead of attacking Go-Daigo’s army, he attacked the Shogunate’s deputies stationed at Rokuhara Tandai, the Kamakura government’s policing agency in the capital.

The renowned warrior, Nitta Yoshisada, far to the north, then rallied his forces to join the battle. He led his army to Kamakura, the shogunate’s nearly impregnable stronghold, surrounded by mountains and the sea.

Avoiding the treacherous mountain passes, Nitta thrust his sword into the sea and prayed for the waters to withdraw so his army could pass through and reach Kamakura.

The sea withdrew, and Nitta conquered the shogunate’s stronghold. Hōjō Takatoki and over 700 of his vassals committed suicide at the Hōjō family temple, Tōshōji.

This marked the end of the Kamakura Shogunate.

The Kenmu Restoration (1333-1336)

With the Hōjō dynasty defeated, Go-Daigo reascended the throne.

Go-Daigo appointed his three generals, Ashikaga Takauji, Kusunoki Masashige, and Nitta Yoshisada, shugo, or military governors. He named his son and heir to the throne, Prince Morinaga, the shogun.

He bestowed upon Takauji a new name, Takeru, meaning valiant warrior. Yet that was not enough.

Samurai who fought for Go-Daigo expected to receive positions of power, rewards, and lands that had belonged to the wealthy Hōjō. Although they were rewarded to a degree, so were aristocrats who had done nothing and even some of the ladies of the court. This caused many samurai to return to their domains filled with dissatisfaction and resentment.

Adding insult to injury, Go-Daigo imposed heavy taxes so that he could build a new Imperial Palace.

The people were not pleased. A rebellion broke out in Kamakura among the remnants of the Hōjō, and the fires of rebellion spread. Takauji asked Go-Daigo if he would name him shogun and send him to quash the uprising. Go-Daigo refused. Takauji disregarded his words and led his army to put down the rebellion, then distributed the conquered lands to his samurai, gaining widespread support.

Go-Daigo sent Nitta Yoshisada to vanquish Takauji and his armies. Unexpectedly, the great general’s horse was felled by an arrow, trapping him beneath its heavy body and making him an easy target for archers. Legend tells us that the noble Nitta pulled out his short sword and severed his own head.

The fallen generals’ soldiers rallied to Takauji, who set off to conquer Kyoto with his reinforced troops.

Takauji took Kyoto, although he was soon forced out by Kusunoki Masashige and the imperial army, and he retired to Kyushu to regroup. There, he gained the support of local lords, also dissatisfied with Go-Daigo’s rule, and was soon marching back to Kyoto with ever-growing numbers.

At the Imperial Palace in Kyoto, Masashige counseled Go-Daigo to retreat to Mount Hiei and allow Takauji to take the capital.

I humbly hope that your majesty will retire from the city for a time and allow Takauji to freely enter Kyoto. I will go to Kawachi and intercept their provisions and stores. Their army will consequently dwindle while ours will increase. Afterward, we can attack the rebels from opposite sides, and we may fairly hope to defeat them.

Go-Daigo dismissed his words and ordered him to battle. Masashige realized that conquering Takauji’s vastly superior forces was impossible. He and his army were being sent to their deaths.

Indeed, at the Battle of Minatogawa, Masashige’s army suffered terrible losses, and his samurai were reduced to a rugged few. Seeing the hopelessness of his situation, Masashige and his brother retired to a peasant’s house. What followed is a conversation that has gone down in history, taught to generations of children.

Masashige asked his brother, “What do you desire after death?”

His brother answered, “Would that I had seven lives to give for my country!”

Masashige replied with eyes alight, “That is indeed best.”

Then the two brothers took their short swords and cut open their stomachs, freeing their spirits to be born again as warriors without suffering the disgrace of defeat.

The victorious Takauji reentered Kyoto. Go-Daigo again fled to Mount Hiei, but in a show of peace, he sent the Three Imperial Treasures to Takauji. With those, Takauji enthroned Emperor Kōmyō.

But, Go-Daigo was a sly one. The Imperial Treasures were fakes. He fled to Yoshino in the south with the real Treasures and set up his own Southern Court.

This marked the beginning of the Nanboku-chō Era, the Northern and Southern Courts period, that continued for nearly 60 years.

Soon thereafter, in 1339, Emperor Go-Daigo died. Takauji, out of respect for the emperor, had Tenryuji Temple in Kyoto constructed as a setting for Go-Daigo’s memorial service.

Hero or villain?

Why is Ashikaga Takauji one of Japan’s Three Great Villains?

It all comes down to who writes the history books.

In this case, 17th-century Neo-Confucian scholar and founder of the Mito school of philosophy, Tokugawa Mitsukuni, 徳川光圀. He began the work on The Great History of Japan, 大日本史, Dai Nihonshi, the writing of its 402 volumes not completed until generations later.

Mitsukuni’s philosophy emphasized extreme loyalty to superiors, and the superiors’ paternal care of their subjects. This type of Neo-Confucianism formed the basis for the strict class demarcations of the Edo period — samurai, farmers, craftsmen, merchants.

Mitsukuni wrote that since Takauji was disloyal to the legitimate emperor, Go-Daigo, by installing another emperor in his place, he was guilty of treason. This disloyalty was the antithesis of what he presented as Neo-Confucian, and as such, samurai, values.

The Mito school’s philosophy informed the Sonnō jōi movement (尊王攘夷, Revere the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians) of the mid-19th century, inspiring the forces that defeated the Tokugawa shoguns. In line with this philosophy, the Meiji government that replaced the Tokugawa Shogunate was based on direct imperial rule.

Emperors Meiji, Taisho, and Showa (known to most Westerners as Hirohito) were treated with god-like reverence by the people of Japan, who were considered subjects, not citizens. All were required to swear allegiance to the emperor.

In light of this philosophy of utmost loyalty, it is easy to see how Ashikaga Takauji was painted as villainous.

His opposite is embodied in the loyal Kusunoki Masashige, who did not hesitate to obey his emperor’s orders, knowing full well he was being sent to his death. He is immortalized in a bronze statue in front of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo and as a Shinto deity at Minatogawa Shrine in Kobe, near where he took his life.

References:

Einin no Tokuseirei, 日本史上最悪だった男~足利尊氏, The Kamakura Period, Japan: Its History, Traditions, and Religions, with the Narrative of a Visit in 1879, by Sir Edward J. Reed.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/