Exploring culinary traditions in Izu and Kochi

While hiking in the Izu Peninsula of Shizuoka, I was lucky enough to visit an unusual shop. Tucked away up a hill in rural Tago, on the western coast, Kanesa Katsuobushi sells bonito. But not just any bonito, they are among a handful of shops that still preserve the fish using the most ancient of methods.

Bonito, sometimes called skipjack tuna, has been a dietary staple in Japan for millennia, evident from the discovery of its bones in Jomon-era (14,000–300 BC) shell middens. And if you’ve ever eaten Japanese food, you’ve likely eaten bonito. It is the foundation of dashi broth, an indispensable ingredient in Japanese cuisine. You might have even seen fish flakes, shaved from dried bonito, dance like an apparition atop tofu, rice, and other dishes.

Katsuo, the Japanese word for bonito, can also be read as “a man who wins,” giving it a favorable connotation. Similarly, the association between the celebratory dish sea bream, called tai, and something happy and auspicious — known as mede-tai — shows how symbolism may contribute to a dish’s enduring popularity.

Because bonito is a seasonal fish, ancient people devised creative ways to preserve it. The earliest documented technique is shiokatsuo, salted and dried bonito, sent from the Izu peninsula as a gift to the Imperial Court during the Nara era (710–794). That is Kanesa Katsuo’s specialty.

To make shiokatsuo, bonito are cleaned, and their cavities are packed with salt. Each fish is then covered in salt and placed in cedar barrels to marinate for two weeks. After marination, the fish are removed, and the salt is rinsed off. The bonito are then hung in the shade and exposed to the cold westerly winds of Izu’s western coast for about three weeks to remove moisture, allowing the fish to dry and mature. As they slowly dry, the proteins in the bonito ferment and mature, concentrating their umami flavor.

Shiokatsuo is produced in early winter in the coastal town of Tago, on the Izu Peninsula, with production peaking in November.

The drying not only preserves but also ferments and ages the fish, concentrating its flavor — not unlike the process used in creating dry-cured ham.

Centuries ago, owners of bonito fishing boats on the western coast of Izu began offering shiokatsuo to Shinto shrines for purification, then serving it to their crews to celebrate the New Year. It was given both as a prayer for bountiful catches and as a guarantee of employment throughout the coming year. If a crew member was not given that gift, he knew he was out of a job.

As part of Shogatsu, or New Year’s celebration, people around Japan place kagami mochi, “mirror rice cakes,” on their house altars to welcome the god of the New Year. Not so in western Izu. Through the centuries, the custom of fishing boat owners offering shiokatsuo morphed into a unique tradition. Here, households and shrines hang shiokatsuo at their entrances to welcome the god of the New Year, as a prayer for bountiful fishing, and in appreciation to the bonito themselves.

This New Year’s tradition has kept alive this ancient method of preserving bonito . Each year in November, the Kanesa shop produces 400–500 shiokatsuo decorated with rice straw to be used during the New Year — called shogatsu-yo. And each year, they quickly sell out.

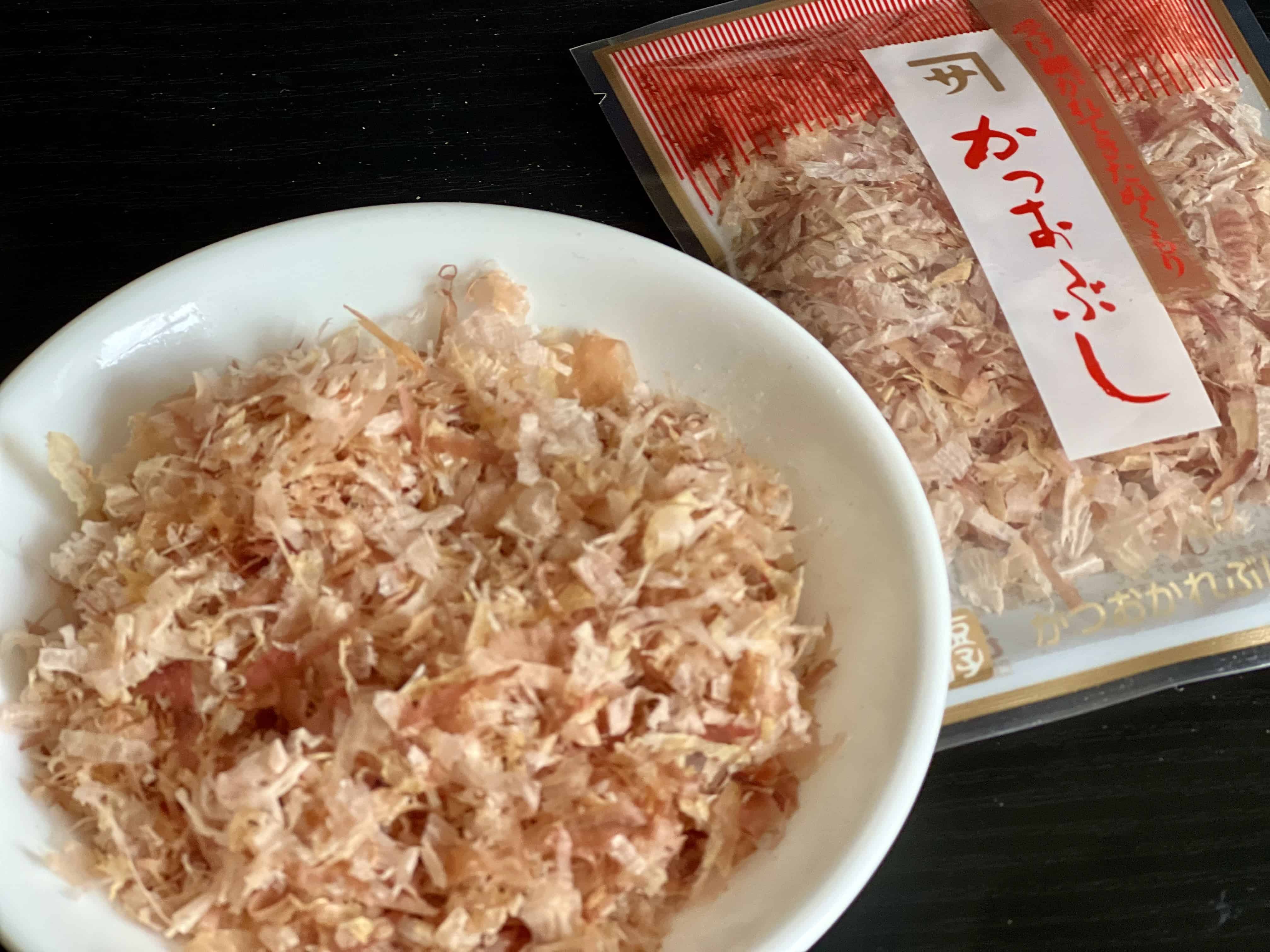

Kanesa Katsuo’s main product, though, is the most common form of bonito eaten in Japan — katsuobushi. Originating in the 17th century, this rocklike preserved fish is flaked and used as a topping for various dishes and is a key ingredient in dashi broth.

Known as the hardest food in the world, katsuobushi takes six months to prepare. First, the bonito is filleted, deboned, and cleaned before being boiled and left to dry on racks in a hot oven. Then the dried fillets are coated with koji mold — the same koji used in the production of sake, miso, and soy sauce — and left to mature for about four months.

This process results in blocks of preserved fish that will later be shaved into “fish flakes.” Special heavy-duty planes are needed for shaving the rock-hard katsuobushi. Your mandoline slicer just won’t do.

Bonito in Kochi

Each year, bonito migrate from the warm waters of southern Okinawa Prefecture along the eastern coasts of Kyushu, Shikoku, and Honshu.

To avail themselves of this bounty of the sea, fishermen in Kochi city on Shikoku island have long used a 400-year-old traditional method called ipponzuri, catching the bonito with a fishing pole. The fishermen first lure a school of these torpedo-shaped, silver-blue fish into a concentrated area and then catch them one by one. A single fish can weigh as much as 5 kilos (11 pounds).

Although fishing using large nets would be easier, this method is avoided to prevent damage to the fish and the unintentional capture of other species.

Seasonal treasures

Bonito are primarily harvested twice a year: from March to May in spring and from September to November in fall. The fish caught during these periods are renowned for their differing yet exceptional flavors.

In the early 17th century, the great haiku poet Yamaguchi Sodo extolled,

The poet was expressing his delight at the harbingers of warmer months — one of which was the first bonito of the season.

Riding the warm Kuroshio current up from the south, these Hatsukatsuo, first bonito, or Noborikatsuo, up-bound bonito, caught between March and May were historically so valued that they were considered almost worth “pawning your wife and children” to obtain. Celebrated for their mild flavor and lower fat content, these fish are said to be best served as katsuo no tataki, or seared bonito.

Those caught from September to November are Modorikatsuo, returning bonito, or Kudarikatsuo, going back bonito. These fish have eaten heartily during their southward migration, resulting in a higher fat content that contributes to a more delicate taste and texture, making it an excellent choice for sashimi.

Kochi is also famous for its himodori katsuo — bonito eaten the same day it is caught — prized for its luxurious freshness.

Bonito is by far the most popular fish in Kochi, particularly Kochi City, where households consume an average of 5,163 grams (11 pounds, 6 ounces) per year — far more than any other city in Japan. This consumption has fostered a wide array of cooking styles.

How bonito is eaten

Aside from katsuobushi, sashimi is widely popular. But in Kochi, bonito sashimi takes a backseat to the local specialty, katsuo no tataki.

To prepare this delicacy, the bonito is cleaned and filleted, and all bones are carefully removed. The resulting quarters of the fish are skewered and held over a fire of rice straw until the outside is seared. This rapid grilling eliminates excess moisture and any lingering fishy smell, enhances the flavor, and creates crispy skin. The seared fish is promptly plunged into ice water to halt the cooking process, then drained and sliced. Katsuo no tataki is served with condiments and sauces that vary by region and individual chef.

Shio tataki, another popular dish, features warm grilled bonito lightly sprinkled with salt. Fishermen often eat it with thin slices of fresh garlic. Other condiments include ponzu, a sauce made from soy sauce and local citrus, as well as salt and garlic, myoga (a mild type of Japanese ginger), scallions, shiso (perilla) leaves, and nihaizu, a 50/50 mix of soy sauce and vinegar.

And there are more. Tosa-maki is rolled sushi filled with seared bonito, shiso leaves, and sometimes raw garlic. Another is harambo, broiled bonito belly served with salt. Chichiko, bonito heart, is generally prepared in one of two ways — stewed in a sweet and salty broth of ginger and soy sauce or simply grilled with salt.

For the more adventurous palate, there’s shuto, written with the Japanese characters for “sake” and “theft.” 酒盗 This peculiar name comes from the dish’s perfect pairing with sake, tempting drinkers to steal the tasty dish. Shuto is a paste made from the salted and fermented organs of bonito mixed with sake, mirin, honey, and onions, resulting in, shall we say, a unique and bold flavor.

Although I traveled far to learn about this amazingly versatile fish, the largest number of bonito caught in the country is right in Kagoshima Prefecture, my home.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/