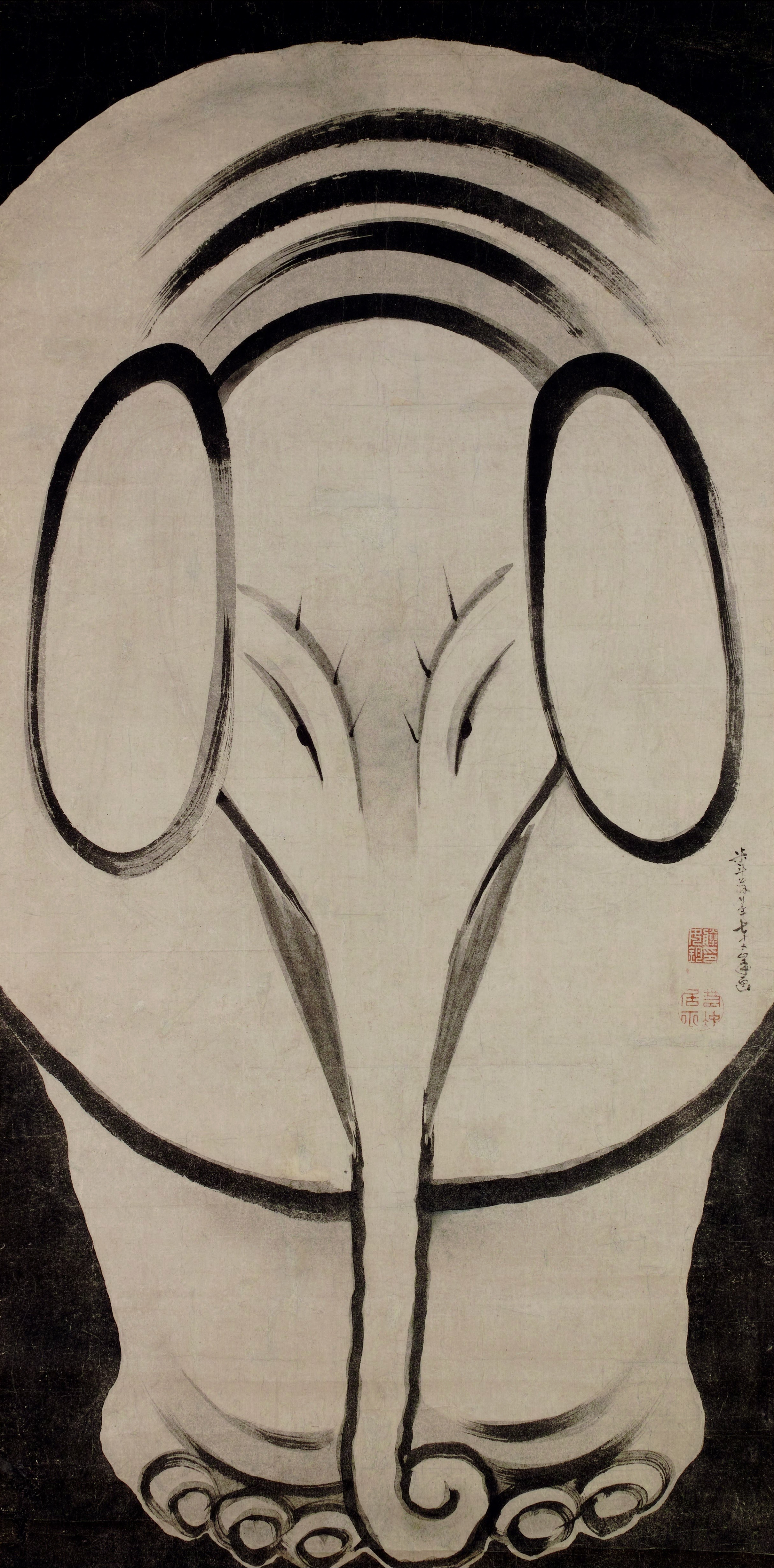

White Elephant of the 4th Imperial Rank

During the Edo era (1603-1867), Japan effectively closed its doors to the outside world. The Tokugawa shoguns had had enough of subversive European influences, such as Christianity, firearms, and suspicious Portuguese and Spanish traders. The third shogun, Iemitsu, slammed the door to all, except very limited, trade.

The Dutch were the only Westerners allowed access to Japan, and that through the highly controlled island port of Dejima in Nagasaki, on the southern island of Kyushu.

The few other windows to the outside world were also tightly controlled: Satsuma, in the south, traded with the Kingdom of Ryukyu (modern-day Okinawa), and through them, surreptitiously with the Qing Chinese; the island of Tsushima traded with Korea; and Matsumae, in northern Honshu, traded with the Ainu—the indigenous people of Hokkaido and northeast Honshu; and by the late 17th century, the Qing Chinese were allowed to trade through their Chinese quarter in Nagasaki.

Yet, as the decades of self-imposed isolation passed, a desire and curiosity for things outside their world grew. In 1720, Shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune relaxed the prohibition on the import and translation of foreign books—except, of course, any Christian books.

His curiosity for the outside world piqued, Yoshimune made an unusual request.

He wanted elephants.

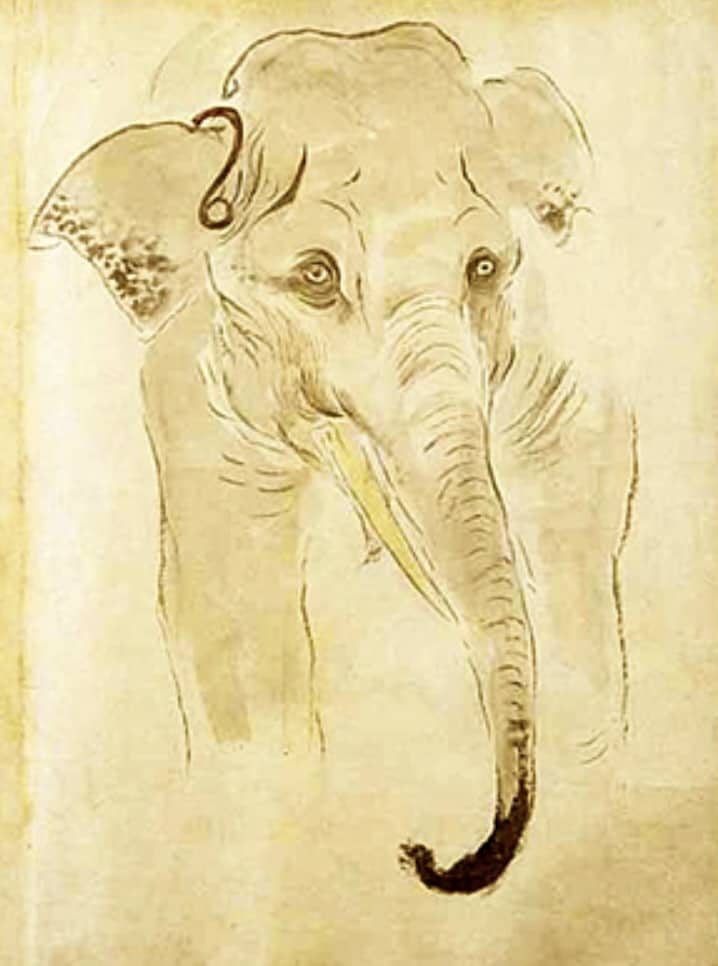

Shiro, the Asian elephant

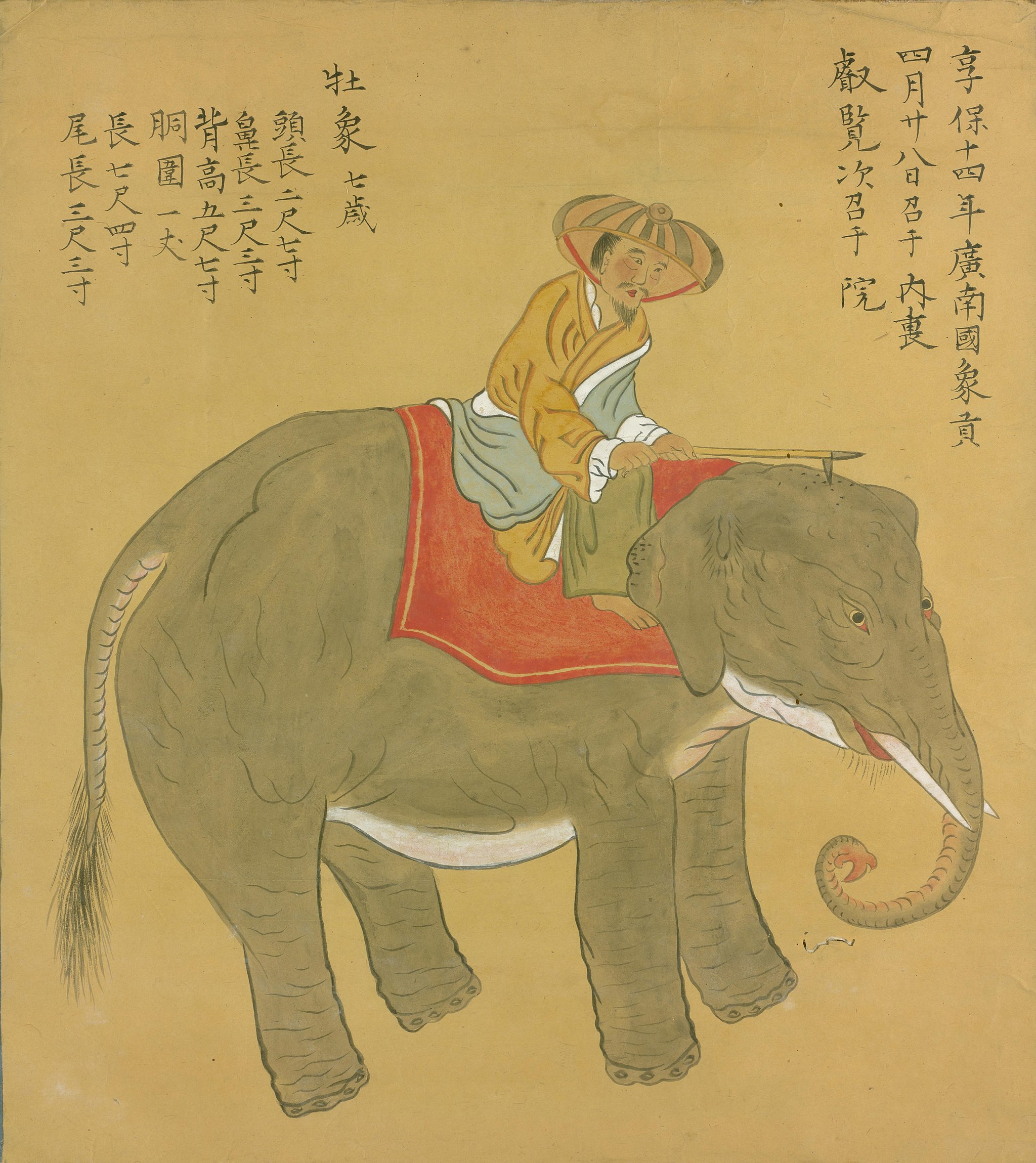

A Qing Chinese merchant in Nagasaki arranged for two elephants to be shipped from Vietnam. A 7-year-old male Asian elephant, whom we shall call Shiro, and his intended mate, a 5-year-old female, along with their mahouts and two translators, spent 27 long days crowded into a specially built Chinese Junk traversing the South China Sea to Japan.

On June 7, 1728, the party came ashore at the port of Nagasaki. The elephants were paraded through the streets of Nagasaki, as shocked onlookers bustled and gasped at the wondrous sight of the magnificent beasts led by their “exotic” Vietnamese mahouts.

The elephants settled into a large stable that had been constructed for them and spent the summer recuperating from their voyage. The different climate and diet—particularly the excessive intake of Japanese sweets fed to her by her well-meaning, yet ignorant, hosts—did not bode well for the female. Just three months after arriving, she died.

The male elephant, Shiro, spent a lonely and cold winter in Nagasaki.

The long road to Edo

On March 13, 1729, Shiro set off on his 1,480 km trek to Edo, now Tokyo.

To make the elephant more comfortable during his long journey, the chief of shogunate finances, Inō Masatake, sent out various decrees.

When the elephant passes, no one is to make loud noises, no temple bells are to be rung, and horses and cattle are forbidden from the streets. Small stones must be swept from the roads and sturdy boats for river crossing prepared. Large stables are to be constructed in the post towns through which the party will pass.

Sufficient feed is to be stored at regular intervals. At each overnight stop, the following food is to be prepared: 60 kg of straw, 90 kg of sasa bamboo leaves, 60 kg of grass, and 50 manju — steamed wheat buns filled with sweet bean paste.

On March 25, our intrepid pachyderm was ferried across the Kanmon Strait and set foot on the main island of Honshu.

Meanwhile, notifications had been sent from the Nagasaki magistrate to the various domains along Shiro’s route, informing them that they must guide the party to the shallowest places to ford rivers, and warning them that they may need to provide lodging at private residences if the beast could not make it to the next post town by dusk. These, and many other instructions, were sent to the domain leaders, who in turn passed them on to the next domain along the route, and on it went.

Elephants are not used to walking on cobblestones such as those paving the Edo-era roads of Japan. Despite the precautions of clearing the road of small stones, Shiro ran into trouble one week after reaching Honshu. He injured his leg and was in obvious pain as he limped along. A stable was quickly built for him where he was allowed to rest and recover.

While at this makeshift stable, he was visited by powerful and famous lords. Mōri of Tokuyama, Asano of Hiroshima, and Ikeda and his mother from Fukuyama.

Recovery made, Shiro resumed his slow journey, reaching Osaka by April 20. After 3 nights’ rest, he set out for the imperial city of Kyoto.

White Elephant of the Fourth Imperial Rank

The street leading into the emperor’s city had been cleared two hours before Shiro’s passing, so throngs took to nearby fields and hills in hopes of catching a glimpse of this extraordinary sight.

In Kyoto, Shiro was housed at the Shōjyōkei-in temple not far from the Imperial Palace.

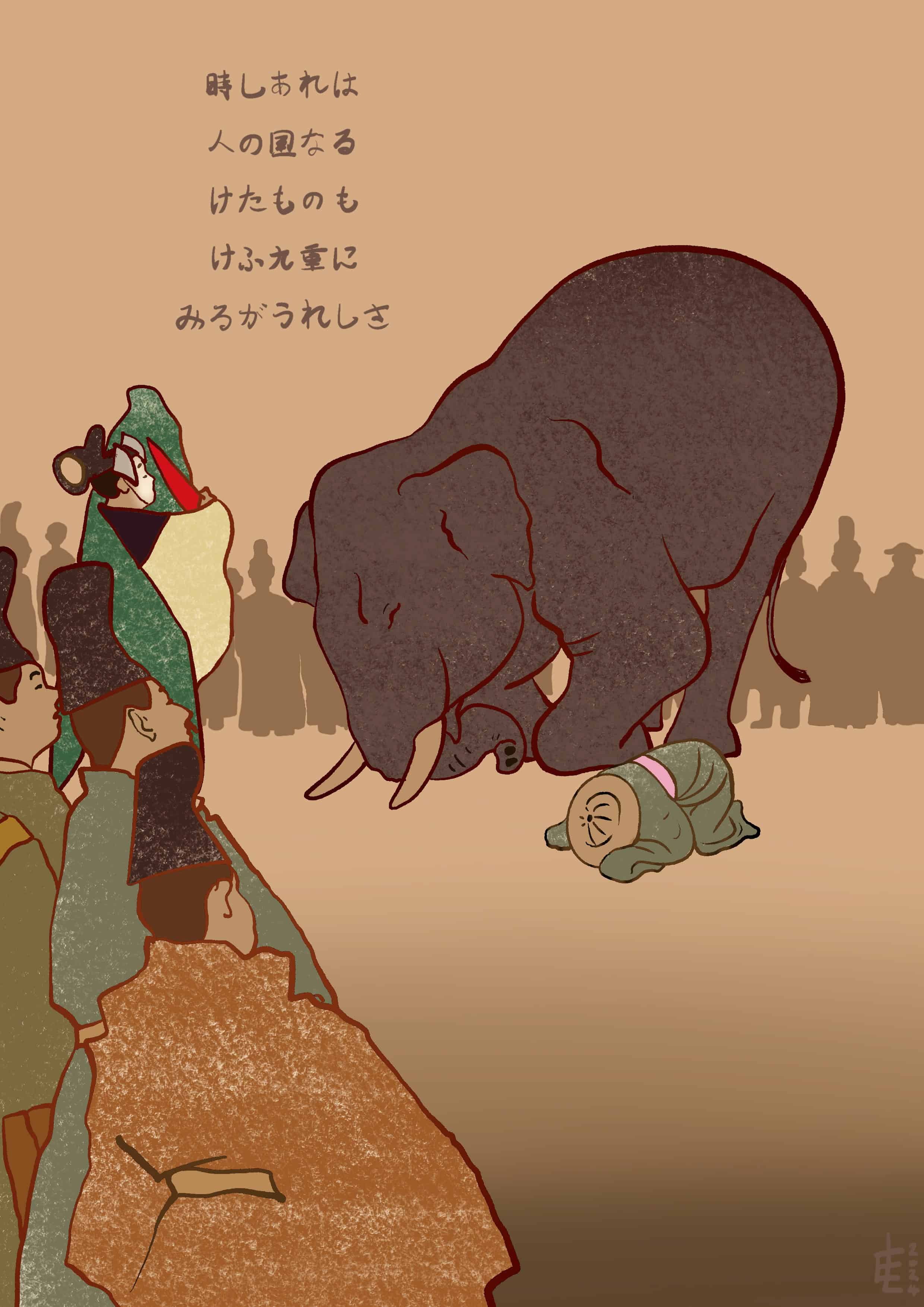

Just like everyone else, Emperor Nakamikado was eager to see him, but it would not be seemly for the son of heaven to visit a mere elephant. With no precedent, what could the emperor do? Only those of the highest aristocratic rank were allowed into the emperor’s presence.

To solve this problem, the emperor bestowed upon Shiro the rank of fourth imperial rank, the same aristocratic level as the keeper of the imperial archives or the lieutenant-general of the imperial guards. This was no small honor!

With this impressive court rank, Shiro was granted permission to pass through the palace gates to meet the emperor.

A stage was built within the palace grounds for the elephant’s audience. When Emperor Nakamikado and his highest-ranking ministers and lords were gathered, our elephant made his appearance.

At 10 am, Shiro came before the stage, bent his front leg, and knelt, bowing his head respectfully before the 27-year-old emperor. The distinguished crowd gasped in awe and wonder.

At 11 am, he was led to the residence of Nakamikado’s father, the retired Emperor Reigen. There, to the astonishment of the assembled dignitaries, Shiro again bowed low, dipping his head nearly to the ground in respect to the elderly emperor.

Emperor Nakamikado was so moved that he wrote the following poem.

At this time

In the world of men

To meet such a beast

In the palace

Fills me with delight

Emperor Nakamikado

The teenage Itō Jyakuchū, 伊藤若冲, a merchant’s son who grew to become well-known for his colorful and realistic paintings of birds, must have been among the crowds who saw Shiro in Kyoto, as his delightful depictions of elephants betray.

The journey continues

On April 29, Shiro and his party headed east to Edo along the Tokaido, one of the two main roads connecting Kyoto with Edo. Passing through Nagoya, he stopped at the castle for an audience with the Lord of the Owari domain, Tokugawa Tsugutomo, and his vassals.

Making their way further east along the Tokaido, Shiro and his party were stopped by the furiously flowing Ōigawa River in Shizuoka. The current was too strong to allow for fording.

Excited local peasants gathered and made a human dam in several rows, shoulder to shoulder, legs spread, and stood in the river upstream. The improvised dam of their bodies broke the strong current. Shiro crossed in safety.

The Fuji River presented the next big obstacle.

This time, 1,900 men worked to create a pontoon bridge. Boats were anchored to posts drilled into the riverbed, then tied together spanning the width of the river. Boards were placed across the boats, creating a makeshift bridge for Shiro to cross.

New challenges arose as they crossed the mountain pass to Hakone. Midway up the slope, Shiro suddenly stopped. Four men gave it their best effort, but no matter how hard they pushed him, he wouldn’t budge.

When a great bubble emerged from his mouth, his caregivers realized Shiro must be ill. They gave him a tonic and allowed him to rest. After time to recover, Shiro walked slowly and unsteadily over and down the pass to Hakone.

He stayed there for four days recuperating before taking to the road again. The grueling journey was wearing on him. He crossed more hastily built pontoon bridges. Nearing total exhaustion, he reached Edo on May 25, 1729.

Shiro’s new home in Edo

The townspeople had been warned not to touch him or toss sweets to him. Nevertheless, the Edo people gave him a wildly enthusiastic welcome, being well prepared for his arrival by the woodblock prints, newspapers, and pamphlets that had been circulating in Edo covering the elephant’s journey.

After being paraded through the city, Shiro was brought to the shogun’s falconry grounds, at what is now the Hama Rikyu Gardens, next to the Imperial Palace.

May 27, Shiro was taken to Edo castle, entering through the Sakurada-mon gate, where he met face-to-face with shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune.

His Vietnamese mahout taught others how to care for Shiro, and the elephant adapted to life on the Hama palace grounds, where Yoshimune took a deep interest in him, visiting him frequently, and even feeding him himself.

As the years passed, the financial strain of Shiro’s upkeep wore on the shogunate. When Shiro trampled and killed one of his keepers, it was decided that he should be sold.

The shogun provided for a stable to be built for Shiro and paid for three years of upkeep, and he was taken to live beside the Jyogan-ji temple in what is now Nakano-ku, Tokyo.

People flocked to see Shiro and to buy elephant-themed merchandise. But like all fads, before long, Shiro’s visitors declined, leaving his new owners struggling. Although doing their best to care for him, Shiro suddenly fell ill. He died on Jan 8, 1743.

Tokugawa Yoshimune ordered that Shiro’s hide and trunk be sent to Kobaien, 古梅園, a maker of sumi ink in Nara. (Sumi ink has been used for centuries for writing, calligraphy, and painting in Japan. It is made from soot and glue derived from animals.) It is said that the hide from his trunk remains there to this day.

Next time I’m in Nara, I will pop in and enquire.

Although Shiro means “white” in Japanese, and his title was the rather wordy, “The White Elephant of Vietnam of Fourth Imperial Rank,” 広南四位白象, according to various diarists of the day, he was, in fact, gray.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/