Blessings from the God of the New Year

Kagami-biraki refers to the Japanese practice of cracking open the hard, dried kagami mochi at the end of the New Year’s holidays, as well as the opening of sake barrels at celebratory events.

Kagami mochi, “Mirror rice cakes”

During Japan’s New Year’s holidays, people display half spheres of mochi, pounded rice cakes, called kagami mochi, “mirror rice cakes.” Two rounded cakes are placed on a wooden offering stand, a smaller cake stacked upon a larger, and topped with a daidai, Japanese bitter orange.

These may look like mere festive decorations, but they play an important role in New Year’s traditions. They are where the Toshi-kami, the God of the New Year, stays during his holiday visit. Kagami mochi also hold symbolic meaning.

Kagami means mirror. This name could have been given due to the shape of the mochi which resembles the round mirrors used for centuries in Japan, or it could be an allusion to Amaterasu’s mirror, one of Japan’s Three Imperial Treasures.

Mirrors are deeply significant in the Shinto religion. They reflect the spirit of Kami, the all-encompassing life force deity, and are often found in shrine sanctuaries.

On top of the “mirror mochi” is a daidai, bitter orange. Daidai is a homonym for “generations.” Much like the many symbolisms of New Year’s osechi-ryori foods, the daidai‘s use on the top of the kagami-mochi represents a prayer for the family’s continuance from generation to generation.

The visit of the Toshi-kami, the God of the New Year

The Toshi-kami is first welcomed into households through the kadomatsu, pine and bamboo decorations that adorn both sides of the front door. The Toshi-kami is not only the god who brings blessings and bountiful harvests in the new year, but he merges with the collective spirit of a household’s ancestors, the sorei, who visits the family at this time.

The period during which the Toshi-kami visits over the new year’s holidays is called Matsu no Uchi, 松の内, “within the pines.”

Burning the kadomatsu

At the end of the Matsu no Uchi, New Year’s decorations are burned, sending the Toshi-kami back to the realm of the spirits.

After the Great Meireki Fire of 1657 that destroyed approximately 60% of Edo (now Tokyo), in addition to other fire preventative measures, the shogun shortened Matsu no Uchi so that the flammable pine decorations would be disposed of sooner. He declared that from henceforth, Matsu no Uchi would end on the seventh day of the first month.

Eating kagami-mochi

Shortly after the kadomatsu are burned, generally around January 11 depending on local customs, the now dried and cracked kagami-mochi is broken into pieces, added to soups or roasted, and eaten by family and friends. This custom is called kagami-biraki, 鏡開き, opening the rice cakes.

By eating the mochi that has been home to the Toshi-kami, people are imbued with spiritual power and blessings for a safe, healthy year.

How the mochi is broken is important, though.

In the age of the samurai, from the 14th to the 19th centuries, it was considered an ill omen to cut the rice cake with a blade as it evoked the image of seppuku, the samurai’s noble suicide, so a wooden hammer was used to break the hard rice cakes.

This method of breaking the rice cakes continues to this day, although the word waru 割る, to split or break, is not used because it is felt to bode evil. Instead, the Japanese use the more positive word hiraku 開く, to open, considered a more auspicious description.

A WORD ABOUT JAPANESE: The verb hiraku takes the ending “i,” hiraki, when used in its noun form, and the first letter changes to “b,” biraki, when joined to another word. For more on the intricacies of the Japanese language, see my article, “Why is Learning Japanese So Hard?”

Another kagami-biraki

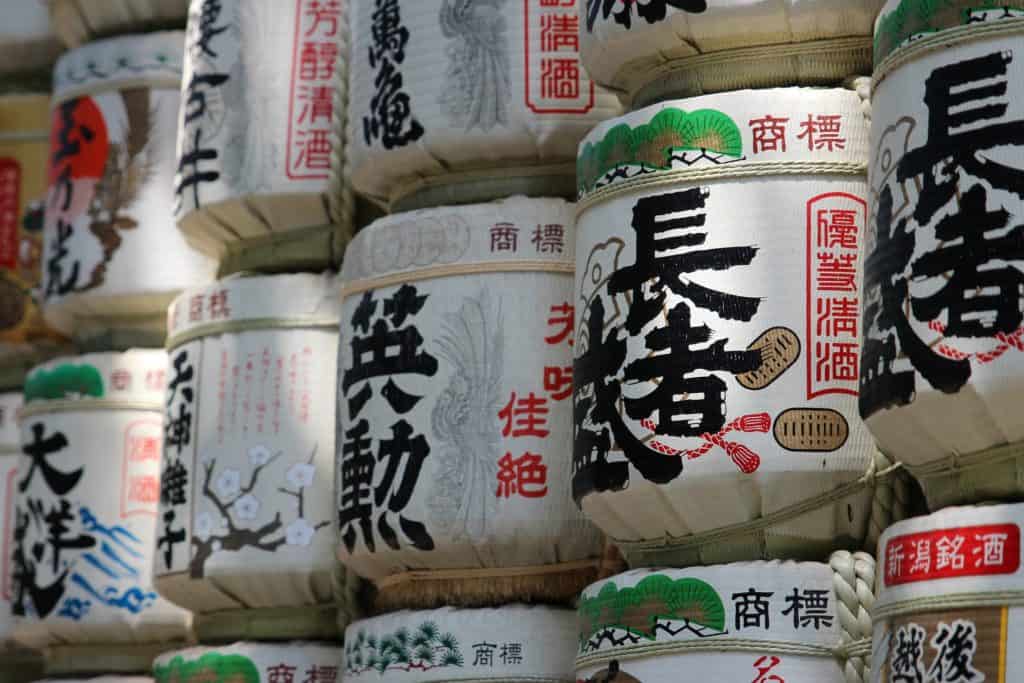

Since ancient times, sake has been offered to the kami, or deity, when performing Shinto rituals. Afterward, the attendees and the priest drink sake together and pray for the fulfillment of their prayers.

This sharing of sake is another type of kagami-biraki. The round wooden lids of sake casks, called kagami 鏡, are cracked open, hiraki 開き, with a wooden mallet and their contents shared. In this case, kagami takes on the meaning of harmony, and hiraki, of prosperity.

The practice of kagami-biraki by opening sake casks has since spread and has become part of many celebrations that mark new beginnings, such as weddings, the start of the new season for martial arts studios or sports teams, and the official opening of new businesses.

A similar custom, kura-biraki 蔵開き, opening store rooms, started in ages past when feudal lords and merchants would celebrate the opening of their storage rooms for the new year, and share sake and rice cakes with their subordinates and customers.

Kagami-biraki is a celebratory event, whether referring to the cracking open of the New Year’s kagami mochi and being imbued with the spirit of the Toshi-kami, or cracking the lid of a 72-liter sake cask and having a grand time drinking it with your community.

https://www.gekkeikan.co.jp/enjoy/qa/sake/sake06.html, https://www.jalan.net/news/article/500808/, The Essence of Shinto,* by Motohisa Yamakage

*affiliate link

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/