Treasure ships that brought goods, wealth, and culture

When I visited the port of Shukunegi on Sado Island a couple of years ago, I spent time at a disused elementary school that had been repurposed as a folk museum. I was fascinated by the relics that filled the old classrooms from floor to ceiling and the plentiful information about a lucrative trade route that flourished in the 18th and 19th centuries.

That trade had been quite a bit more than a difficult get-rich-quick enterprise. It changed history.

Kitamaebune Trade

From the mid-Edo Period until the 1880s, Kitamaebune ships were both conduits for trade and, as a consequence, widespread cultural interchange. These sturdy wooden vessels, with their distinctive square sails, were not just cargo vessels — they were floating trading houses.

The shipmasters would buy and sell goods at ports along their extensive voyages, which spanned from remote Hokkaido, along the coastal regions of western Honshu, and around Shimonoseki to the bustling city of Osaka. This trade route, as well as the ships themselves, became known as Kitamaebune.

“Kitamae” was the word used by people in Osaka and the Inland Sea area for the “Sea of Japan side” of Honshu. Thus, ships arriving from the Sea of Japan were referred to as Kitamaebune, or “Sea of Japan ships.” On the Japan Sea coast, they were generally known as Sengoku-bune, although some referred to them as “Bai-bune” or “Double ships,” reflecting the potential for shipowners to double their profits in a single journey.

Such profits were made possible because of the lack of rapid communication. Before the advent of telegraphs, savvy merchants realized that they could capitalize on regional price variations to earn substantial profits. By buying goods at lower prices in one area and selling them at higher prices in another, they took advantage of price differentials to maximize their earnings.

The origin of the Kitamae sea route can be traced to Maeda Toshitsune, the third lord of the Kaga Domain, now Ishikawa Prefecture. At that time, Osaka served as the economic center and a major trading hub, and each domain had a warehouse in the area. To transport rice from Maeda’s domain to Osaka, the Kaga clan had previously unloaded the cargo at the port of Tsuruga and transported it overland and via Lake Biwa to Otsu, Kyoto, and Osaka. However, this process was laborious and inefficient.

In the early 1600s, Toshitsune decided to ship 15,000 kilos of rice from the Sea of Japan southward around Shimonoseki through the Seto Inland Sea to Osaka. In 1672, this route became official when the Tokugawa shogun ordered Edo merchant Kawamura Zuiken to chart the Sea of Japan passage connecting Hokkaido and Osaka, and the Kitamaebune route was born.

The Ships

The early Kitamaebune were small, single-sail, oared vessels that could carry up to 75,000 kilos of cargo. Due to the limitations of their design and the challenging conditions of the sea, they could only complete one round trip between northern Japan and Osaka per year, from spring to autumn. In winter, when the sea was rough, the ship would be moored near the harbor and the sailors would return home on foot. With the arrival of spring, they would reunite at the harbor and prepare to set sail.

By the beginning of the 18th century, the first 24-meter-long Sengokubune were built. Sengokubune means “1,000 koku ships.” In traditional Japanese measurement, one koku equals 150 kilos. 150 kilos of rice was considered the amount needed to feed one man for a year. Taxes were calculated in terms of koku, samurai received their wages in koku, and the wealth of daimyo lords was measured by the number of koku of rice their domains produced. Thus, a Sengokubune, 1,000 koku ship, could carry an impressive 150 tons of cargo.

These new vessels boasted solid hulls, sharp bows designed to cut through the waves, and large, single-piece square sails. With these advancements, Sengokubune could complete the journey between Hokkaido and Osaka in just 12 to 13 days, marking a vast improvement in efficiency and transportation speed. Because they could sail without the need for oarsmen, these large robust vessels could be operated by a crew of just a dozen people.

Upon arrival at a port, the shipmasters had to provide a document detailing the purpose of their voyage, the number of crew members, and proof that no Christians were on board. This paper, along with inventory lists, receipts, and other essential documents were kept in specially designed waterproof chests that would float in the event of a shipwreck.

And shipwrecks were not uncommon. Before setting out, sailors would visit Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples to pray for safety. Pictures of ships offered as votive tablets, called ema, can still be seen in shrines and temples along the Kitamaebune route. These were offered both as prayers for safekeeping and as tokens of thanksgiving. In some cases, shipwreck survivors even cut off their hair and attached it to ema tablets in gratitude to the gods.

The Cargo

The Kitamae route encompassed over 100 ports along the Sea of Japan, primarily in the Hokuriku region. These served as home ports where shipowners resided, and from there, the ships sailed to Osaka. After loading necessities such as sugar and sake in Osaka, the ships started on their journeys to Hokkaido, stopping at ports along the way to stock up on items to sell.

The shipmasters purchased specialty items from each area. In the ports along the Seto Sea, they bought salt from the numerous salt farms that dotted the coast. From Shimane, they bought iron. In Fukui, paper and knives. To ensure stability, granite slabs were used as ballast, and on top of that, the hulls were filled with an eclectic mix of goods including vinegar, tobacco, candles, pottery, cotton, textiles, indigo, dolls, and sweets.

Upon reaching each port, the shipmasters would sell whatever goods they had in store that would make a handsome profit. Continuing their journeys further north along the Honshu coast, they would replenish their cargo. From the Hokuriku ports, they bought buckwheat, medicine, and especially rice and straw products to sell in Hokkaido where it was too cold for rice to grow.

From Hokkaido, the Kitamaebune mainly carried marine products to Osaka and ports along the way. This included valuable commodities like kombu kelp, herring, dried sardines, dried sea cucumber, salmon, and cod. The ships would set out in August, stopping at ports to sell and pick up more goods. Aside from their main cargo of rice, other items included sand iron, kozo mulberry stalks (the raw ingredient of Japanese paper), pots, agricultural equipment, salt, and copper Buddhist implements, incense burners, and vases — and safflower, a popular item in Kyoto where it was used to make lipstick and dye.

The abundant herring from the Hokkaido seas served for decades as an important source of fuel and fertilizer. The fish were processed to extract the oil, and the remains were fermented. This nutrition-rich mash was used as fertilizer for the rapidly developing cotton industry in domains along the Seto Inland Sea. Its sales brought in five to ten times its purchase price.

The profits from a single Kitamaebune voyage could amount to 60-100 million yen in today’s currency (US $450,000-$706,000). Some shipowners amassed fleets of as many as 200 large and small ships, making some families billionaires. The Honma’s of Sakata, in present-day Yamagata Prefecture, were one such family who, through scrupulous trade, grew from lowly merchants to become the largest landowners in Japan. Their wealth surpassed that of feudal lords.

An expression of the day was, 本間さまには及びもないが、せめてなりたや殿様に, Honma-sama ni ha oyobi monai ga, semete naritaya tono-sama ni. “Becoming a Honma is too far out of reach, but let me become a lord, at least!” This phrase encapsulated the ambitions of the merchant class, whose dreams of financial success focused on the Kitamaebune trade.

The Sailors

The allure of working on these treasure ships attracted many young men, but the job had its difficulties. Sailors faced demanding work, braving the perils of shipwrecks and enduring six-hour shifts through the night. Their salaries were low, around ¥200,000 to ¥300,000 per year in today’s terms (US $1,500-2,000), yet people still clamored to work on these ships because the job also had its perks.

Shipwrights were allowed to load and sell private goods, keeping the profits for themselves. Other crew members received a bonus known as kiridashi, which amounted to 5 to 10% of the ship’s sales. It’s easy to imagine how this incentivized the crew to handle the cargo with care. On a Kitamaebune carrying 15 tons of goods, a sailor’s bonus could reach a remarkable 10 million yen in today’s value (US $70,500). It’s no wonder that these jobs were popular.

A prerequisite for employment was that prospective crew members had to be from the same village as the shipowner, or else they had to provide a guarantor. Given the substantial profits at stake, having a trustworthy and capable crew was paramount. Hiring crew from the same region engendered trust, fostered camaraderie, and strengthened bonds.

Individuals could start their career on a Kitamaebune as an apprentice ship’s cook at the age of 14 or 15 and gradually progress to become a mariner. Although it took around 30 years to advance through the ranks, the hope was that eventually, a sailor could save enough money to buy his own ship and become a millionaire.

Cultural Impacts

The far-reaching impact of the Kitamaebune trade cannot be understated. The numerous ports along the route served as centers of shipbuilding and trade, giving rise to unique local cultures and industries. As the ships traveled, they transported not only goods, but also ideas, customs, and knowledge, contributing to the exchange and spread of cultural influences.

One noteworthy area is pottery and ceramics. The Kitamaebune trade introduced distant pottery styles from Arita and Seto to ports along the Sea of Japan coast. This allowed the people in those regions to incorporate these styles into their evolving pottery tradition.

Food culture also experienced significant transformations through the Kitamaebune trade. The introduction of kombu kelp from Hokkaido led to a thriving industry of kombu-based products in the Kansai region, such as kombu-maki rolls and umami-rich dashi broth. The popularity of kombu dashi spread throughout the country, and today it is an essential ingredient in Japanese cuisine.

The trade also facilitated the dissemination of wagashi, exquisite Japanese sweets that originated in Kyoto to accompany bitter green tea. These artistic confections added a touch of class and sophistication to the shops that served them in the northern regions.

A lesser-known Kyoto specialty called imobo, or “potato stick,” owes its origin to the Kitamaebune. This curious dish, which is not actually made from potatoes, was created using affordable dried cod from Hokkaido and a local variety of taro root. In an attempt to imitate the new, exotic, and expensive Satsuma sweet potatoes, the fish and taro were cooked together for days until they blended, resulting in a texture and look somewhat resembling boiled sweet potato sticks.

Architectural influences also spread through the Kitamaebune trade. Construction techniques that were prevalent in Kyoto were transmitted to the northwest coast of Honshu, leaving a lasting imprint on the region.

Construction materials, such as a valuable stone called shakudani-ishi, were carried on the Kitamaebune ships. This light blue volcanic tuff, mined in Fukui Prefecture, was sought after for crafting Buddhist statuary and building shrine foundations. Even the granite stones that served as ballast were repurposed for building bridges and roads.

Music traveled with the sailors on the Kitamaebune, resulting in the transformation and adaptation of folk songs along the route. The Kyushu song “Haya-bushi” journeyed north and evolved into local folksongs still sung in Niigata and Aomori prefectures. Similarly, a popular song originating from Sakata port near Osaka made its way to Niigata, where the lyrics were adapted to depict the people and experiences associated with the Kitamaebune ships.

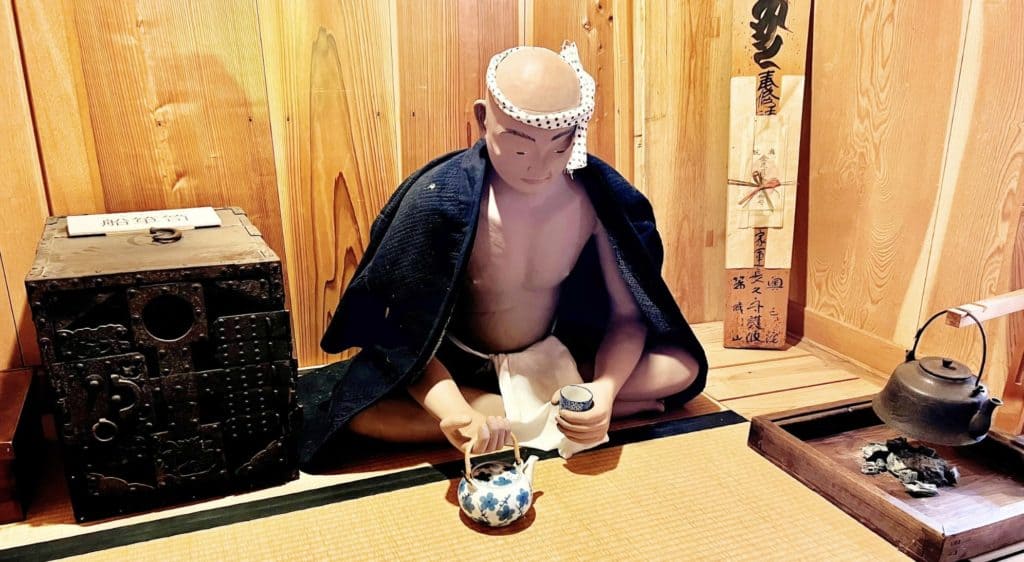

The port towns along the Kitamaebune route bustled with restaurants, inns, and teahouses catering to the boatmen. Diverse populations were drawn by the lure of the trade and the prosperity it brought, from geisha to master carpenters. Boatmen became known not only for their navigation and trade expertise but also for their refined appreciation of poetry and the arts. As they returned to their respective regions from the Osaka-Kyoto area,they brought back some of the sophistication and vibrant culture they had experienced.

Fashion was another area influenced by the trading ships. During the Edo Period, cotton cultivation began in the Kansai area, but the northwestern coast of Honshu was too cold for it to grow. To acquire this coveted and versatile fabric, people in those regions purchased discarded cotton garments from Osaka, transported via the Kitamaebune ships. They recycled the cloth using a method called sakiori — tearing the cloth into strips and reweaving it with thread. This technique created a uniquely textured material. Sakiori eventually gave rise to sashiko, a renowned form of Japanese embroidery.

The Kitamaebune boatmen were easily recognizable by their distinctive attire: garments of sakiori cotton, a rope in place of an obi belt, and a portable brush and ink case attached at the waist. Their clothing was not only practical, but it revealed their identity and role in the trade.

The End of an Era

As the Meiji Period (1868-1912) unfolded, technological advancements such as railroads, steamships, and telegraph communication brought about the gradual decline of the Kitamaebune trade. The rapid dissemination of commodity prices throughout the country reduced the shipowners’ ability to capitalize on price variations, impacting their profits. The majestic Kitamaebune sailing vessels were soon replaced by more efficient steamships, and the era of these iconic ships gradually faded.

Furthermore, in 1885, a government regulation banned the construction of Japanese-style ships exceeding 500 koku. This dealt a severe blow to the shipbuilding industry along the Kitamaebune route, forcing many businesses to shut down. Some shipbuilders chose to emigrate to Hokkaido, a newly opened frontier, where they could utilize their skills in the development of the burgeoning territory.

The legacy of the Kitamaebune trade, however, endures in the economic and cultural aspects of the regions along its route. Its influence can be seen in the local traditions, culinary practices, and architectural styles that were shaped by this dynamic era of maritime commerce.

One can only imagine the anticipation felt by the locals eagerly watching the horizon for the white sails of these treasure ships. The arrival of each surely brought with it a wave of excitement and wonder, as the communities knew that within their hulls lay a wealth of goods from distant lands. The joy of being connected to worlds they could only dream of must have been an extraordinary experience for the people along the Kitamaebune route.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/