And the birth of one of Japan’s most mysterious natural wonders

Reflected in the still waters of Japan’s fourth-largest lake, Inawashiro, the 1,816-meter-high Mount Bandai stands tall and proud to the north, an iconic symbol of Fukushima Prefecture. Viewed from the lakeshore to the south — the side called Omote-Bandai, “Front Bandai” — the stratovolcano appears smooth, its verdant, irregular peaks like ordered crowns atop the mountain. The surrounding land is a picture of tranquility, with gentle plains covered in a patchwork of orderly rice fields.

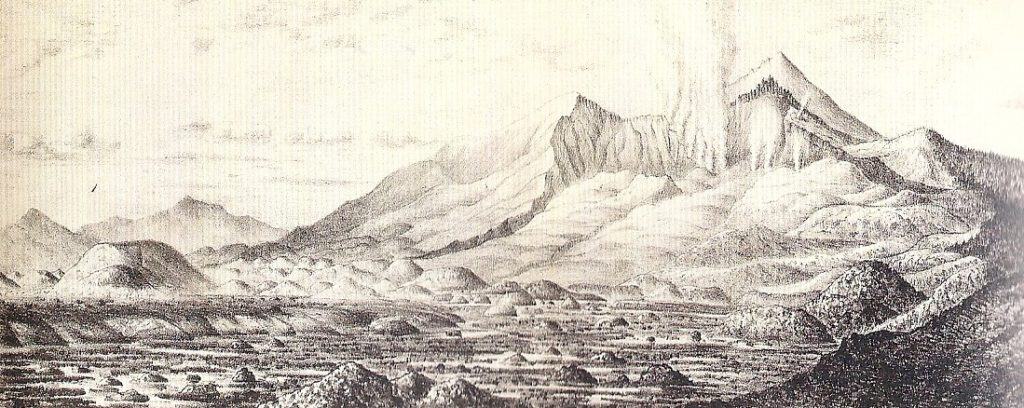

From the volcano’s northern side — Urabandai, “Behind Bandai” — it is as if one is looking at a different mountain. Gone are the smooth slopes of its southern face. Here the mountain seems to have been cleft in two, its tall, craggy, desolate peaks bearing the scars of a terrible eruption that took place in a single day in 1888.

But in the wake of that horror, nature created a masterpiece.

Goshikinuma

Goshikinuma, “Five-Colored Ponds,” is the collective name for numerous ponds and marshes formed after the eruption of Mount Bandai in 1888. The eruption forced acidic substances into the groundwater that flowed into the ponds. These acids chemically changed into aluminum silicate crystals and mixed into the water. The crystals reflect specific wavelengths of light creating the mysterious colors seen in the ponds.

The marshy pools’ hues range from cobalt blue, emerald green, and turquoise blue, to pastel blue, with occasional hints of crimson. These colors vary based on seasonal changes, weather conditions, viewing angles, and the concentration of volcanic substances in the water. The curious and changing colorations of the water gave rise to another name for the Goshikinuma — Shinpi no Koshō, “Mysterious Marshes.”

Mount Bandai’s 1888 Eruption

Like many stratovolcanoes, Mount Bandai contains several vents. Before that eventful day in 1888, three distinct peaks crowned the mountain — the higher western peak, known as O-Bandai; the eastern peak, Kushi ga Mine; and between these was the third peak, a sort of shoulder to O-Bandai, called Ko-Bandai.

From July 8–10, small earthquakes were felt at the northern base of the volcano, growing in intensity over the 13th and 14th. Despite these seismic tremors, no changes were observed in volcanic activity.

However, starting on the morning of July 15, a series of events would completely alter the topography of the area.

It began with two powerful earthquakes, the first striking around 7:30 am, followed by a second quake and colossal explosion, whose deafening roar was heard as far as 100 km away.

The force of this initial blast uprooted trees over a meter in diameter and stripped bark from others. Confusion and terror ripped through the villages at the mountain’s base as people and farm animals were hurled into the air, their clothing torn from their bodies. Airborne debris, a mix of volcanic rock and twigs, caused injuries to many. Ash carried by prevailing winds fell as far as the Pacific Coast.

About twenty additional eruptions followed, unleashing further devastation upon the foothills of Bandai. Three hot spring inns nestled in the foothills were filled with people seeking the healing benefits of the therapeutic waters. Tragically, the staff and guests were bombarded with cinders and ash, and many lost their lives. The death toll would reach 477, Japan’s highest number of fatalities from volcanic disasters since the Meiji era began in 1868.

Within ten minutes of the initial blast, a massive collapse caused by a pyroclastic surge set an avalanche of debris cascading down the volcano’s northern flank. This tsunami of earth crashed through the Biwazawa Valley, obliterating the once-thriving village of Shibutani and burying half of the houses in the nearby village of Mine.

Approximately two hours after the eruption began, an eerie calm settled over the torn landscape. Onlookers wondered if the worst was over.

Suddenly, the air was filled with deep, furious rumblings. Ko-Bandai, the peak between O-Bandai and Kushi ga Mine, collapsed, unleashing a mighty torrent of stone and earth. This colossal avalanche, towering 75 meters high, surged down the mountain with incredible force at speeds of 80 kph. It crushed everything in its path as it hurtled down the mountainside in a cascade of destruction, spreading into a fan shape over an incredible 34 square kilometers in the Nagase Valley below and extending 15 km to the north of Mount Bandai.

The entire mountain was transformed. The northern side was hollowed out, creating a vast, gaping, horseshoe-shaped caldera where the crown of Ko-Bandai once stood. This enormous abyss measured approximately 2 km from north to south, 1.5 to 2.1 km from east to west, and reached a depth of 400 meters. The collapse of Ko-Bandai is estimated to have moved a staggering 1.5 cubic kilometers of earth.

The deposition of debris created the distinctive topography of Urabandai, a land dotted with innumerable small hills and valleys. As water accumulated in the low-lying areas, many small lakes and marshes, including the Goshikinuma, took form. The hilly topography of the Urabandai Plateau extends not only to the land but can also be seen beneath the waters of its ponds.

The Aftermath

As the rumblings ceased and the ash cleared from the air on the day of the eruption, Fukushima Prefecture dispatched prefectural police officers to assist the local officials who had already started rescue activities.

Within days, the rising waters from the rivers, choked by the massive debris avalanches, threatened to engulf surrounding villages. The roads were already underwater, posing further obstacles to rescue missions.

Soon, the inevitable unfolded — two lakes to the north and south of the six hamlets of Hibara Village merged, creating the Lake Hibara we know today. An abandoned hamlet lies beneath the water’s northern surface, the vestiges remaining on the lake floor 30 meters below. Only the top of a torii gate extends above the water’s surface, a poignant reminder of the town’s former existence.

The southern portion of the lake blankets another hamlet, first buried under debris from the landslide. Of the original six hamlets of Hibara Village, two were submerged beneath the lake, three were swallowed up in the debris avalanche, and only one, Wasezawa, survived.

Within two days of the eruption, Emperor Meiji announced that he would grant an imperial gift of 3,000 yen towards the relief efforts — a considerable sum at the time. It is worth noting that only two decades earlier, the people of Aizu had fought against the emperor’s new government during the Boshin War. Considering their history, the emperor’s benevolence and concern in the face of this disaster must have deeply touched the hearts of those affected.

Physicians from Tokyo Imperial University, now Tokyo University, were dispatched to care for the injured. Empress Shōken urged the nascent Japanese Red Cross to join the relief efforts, marking the organization’s first peacetime relief work.

As news of the disaster spread throughout Japan, a wave of volunteers rushed to Fukushima eager to lend a helping hand. Inns and private houses in the area filled. Generous donations flowed in. The displaced people soon had new housing, and Hibara Village was reconstructed from the ground up.

Today, Mount Bandai is continuously monitored by the Japan Meteorological Agency to detect any potential volcanic activity. The once-devastated land has undergone a remarkable transformation, making it a popular destination for skiing and vacations.

The only visible traces of the catastrophic eruption are the horseshoe-shaped crater on the northern face of Bandai and the hummocks in Urabandai formed by the debris avalanches. The countless trees once described by a volcanologist as “laying prostrate on the ground in thousands” are nowhere to be found, and the blast deposit is now concealed by thriving vegetation.

But all that vegetation did not rebound spontaneously.

Read the continuation of this story in Endō Genmu — The Unsung Hero of Urabandai Reforestation.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/