Off the beaten path in Japan

Pre-pandemic, when Japan’s borders were open to tourists, I had the pleasure of taking groups of adventurous foreigners along some of the ancient roads of Japan.

A favorite was the Nakasendo Way, one of five main roads used during the Edo era (1603–1868) for daimyos to travel from their domains to and from the capital, Edo (Tokyo).

The Tokaido, known today as a shinkansen route, and the Nakasendo were the two highways that linked the capital of Edo to the imperial city of Kyoto. Like all of the five main roads, they started at the Nihonbashi Bridge in Tokyo.

The Tokaido went along the coast, crossing wide rivers, before meeting up with the Nakasendo for the final stretch to the Sanjo Bridge in Kyoto.

The Nakasendo Way, 中山道, “the way through the mountains,” took a 500 km route through the heart of Japan. It was not only used by daimyos, merchants, and pilgrims, but princesses who were to be married to shoguns.

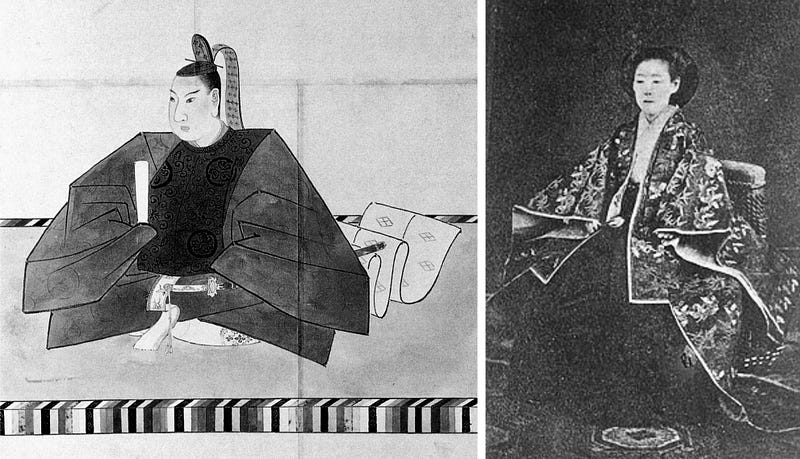

The most famous of these was the 16-year-old Princess Kazunomiya, who was compelled to leave her fiancé in Kyoto and marry the 14th shogun, Tokugawa Iemochi, in 1862.

The princess’s entourage consisted of 10,000 people who had been sent from Edo to escort her, plus uncounted porters and servants with baggage and animals. The royal procession took three days to pass any one point along the road. It must have been a sight to see!

Remarkably, Princess Kazu and the young shogun had a happy, though brief, life together. Iemochi, who suffered from ill health, died when he was 20, after only four years of marriage. Kazunomiya then became a Buddhist nun and went on to quietly influence events leading to the Meiji Restoration.

But I digress.

History of the Nakasendo Way

Although much of the Nakasendo Way dates from the 7th century, it rose to importance some 1,000 years later during the Edo Era.

To keep a close eye on the daimyos, and keep their wealth in check by imposing extra expenses upon them, the Tokugawa shoguns required each lord to maintain a second estate in Edo where his wife and children would live. Lords were to alternate spending one year in Edo and one year in their domain.

Daimyo processions were a common sight along the five roads, and a chance for the lords to demonstrate their prestige. They were fantastic parades with banners held high, porters carrying boxes, pack animals, and decorated palanquins.

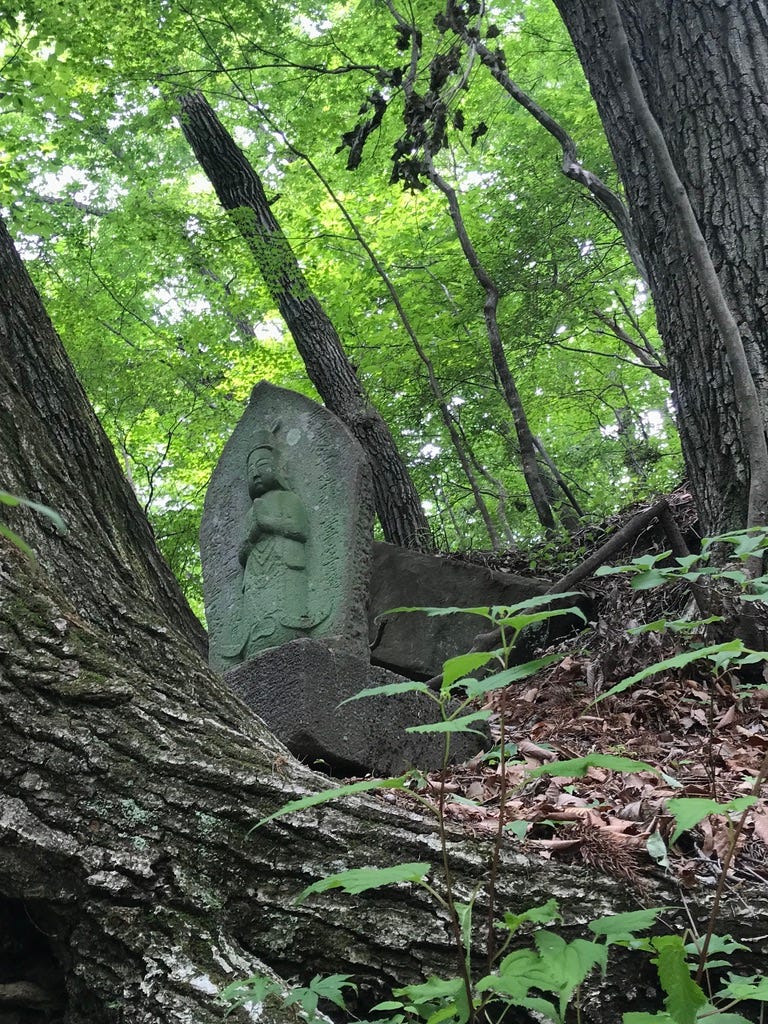

To expedite travel, the Tokugawa shoguns made sure the five roads were well maintained. There were distance markers, tea houses, statues of deities for the protection of travelers and their animals, and importantly, post towns. These towns, separated by an easy day’s walk, provided travelers with lodging, meals, straw sandals, horses, and porters.

“Barrier stations” along the road were staffed by intimidating samurai officials who searched travelers to ensure that no noblewomen were traveling away from Edo in disguise and that no weapons passed through. If women were caught leaving the capital, the shogun would assume that her husband was sending her away before attempting a rebellion.

Today, much of the Nakasendo is laid over with highways, but there are still beautiful and walkable sections, most notably “The Kiso Road.”

The Kiso Road

The Kiso Road is the portion of the Nakasendo roughly halfway between Tokyo and Kyoto. It generally follows the Kiso River as it winds between the steep mountains of southwestern Nagano Prefecture.

90% of the Kiso Valley is covered in forest. The area is well-known for its magnificent Hinoki cypress trees. So valuable is the aromatic, water and insect-resistant wood of these Hinoki trees that cutting one down during the Edo Era was punished by death. The peasantry knew all too well the slogan:

枝一本、腕一つ

木一本、首一つ

Cut a branch, lose an arm.

Cut a tree, lose a head.

The forests are still protected, but, thankfully, today’s laws are less draconian.

Walking the Kiso Road

Heading towards Tokyo, the Kiso Road begins in front of the rustic Shinchaya inn, outside of the post town of Magome, in Gifu Prefecture. A stone marker in front of the inn is engraved with the words, 是より北 木曽路, “North from here is the Kiso Road.”

Walking along the Kiso Road, we pass by old farmhouses, rice fields, forests, and gardens. The only sounds are the cheerful chatter of birds, the creaking of bamboo against bamboo, and the rustling of the leaves overhead.

Our journey takes us through many post towns. Allow me to introduce you to a few.

Magome

Our path from Shinchaya soon climbs a steep hill and we enter Magome, a carefully preserved post town nestled on a slope overlooking a vast panorama of mountain peaks. Its friendly shopkeepers sell traditional snacks, locally made products, and souvenirs.

From there, the trail takes us through forests and over the 801-meter Magome Pass, where we enter Nagano Prefecture.

Our descent brings us by two waterfalls, Odake and Medake, the Male and Female waterfalls, under which the legendary ronin swordsman, Miyamoto Musashi, cooled his ardor for his love and rededicated himself solely to the way of the sword.

Tsumago

The next post town is Tsumago. This is one of many towns that was bypassed by highways and train lines and subsequently fell into poverty in the mid-20th century.

Luckily, in 1968, the residents realized that they possessed a treasure. They agreed to renovate buildings using only traditional materials. They removed electric wires and vending machines from the streets. The community leaders agreed that none of the buildings in the town would be “sold, rented out, or destroyed.”

Thanks to the efforts of those residents, in 1971, Tsumago was the first town in the country to be recognized as an “Important Preservation District for Historic Buildings.” Today, there are 126 such districts throughout Japan.

Each evening along our journey is spent at a traditional inn. We arrive in time to bathe and dress in yukata robes before enjoying a feast of local vegetables, fish, meat, tofu, and sake.

Nagiso

From Tsumago, our route continues to take us through peaceful countryside, terraced rice fields, and forests. We get our first sight of the crystal clear waters of the Kiso River as we approach the town of Nagiso.

We stop by a wooden suspension bridge, originally built in 1912 by the wealthy businessman, Fukuzawa Momosuke. He was the first to bring hydroelectric power to the region, harnessing the swift waters of the Kiso River. Some of the original power plants he built remain.

Our days continue to take us over undulating hills and through forests, visiting more pleasant post towns and relaxing inns. Our muscles haven’t felt sore at all, perhaps due to the rejuvenating waters of our pre-dinner baths and the long, comfortable nights of sleep between soft futons.

Narai

We pass through the post town of Yabuhara, once renowned for its wooden handicrafts. There are still a couple of old shops left selling handmade combs and other treasures from bygone days.

From there, we hike up through beautiful forests till we reach a small shrine and large Torii gate which give the pass its name, Torii Pass. For travelers coming from Edo, this was their first view of the sacred Mount Ontake, which we can just make out in the distance.

We head down to the post town of Narai, famous for its fresh spring water, where we enjoy a lunch of soba noodles, the local specialty.

Our journey ends there, although we are still 10 km from the stone that marks the northern end of the Kiso Road. Soon after Narai, the old Nakasendo Way becomes Highway 19.

It is time for us to change out of our hiking boots and head to Tokyo before making our way home.

I hope that each one of you will have the opportunity to walk the ancient roads of rural Japan someday. It is a different world, and one well worth savoring.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/