Revolutionizing Japan and Embracing the Modern Age

As I stroll through the streets of my hometown, Kagoshima, in southern Kyushu, and trek across the volcanic mountains of Kirishima to the north, I find myself retracing the footsteps of the legendary Sakamoto Ryōma. This influential samurai, who arrived by ship to Kagoshima in the mid-19th century with his new bride, hiked the rugged mountains, soaked in healing hot springs, and even is said to have removed the upended sword from the top of Mount Takachiho placed there by Ninigi no Mikoto, the ancestor of Japanese emperors.

A much-loved and romanticized figure in Japan’s history, Sakamoto Ryōma defied his low-ranking samurai origins to wield immense political influence. He is widely celebrated for his pivotal role in toppling the 265-year rule of the Tokugawa shogunate, ending feudalism, and ushering in Japan’s modern era. In his short but storied life, Ryōma risked death by leaving his clan, reconciled former foes, and authored articles crucial to the formation of the Meiji government.

Challenged by frail health from a young age, Ryōma faced early adversity when his mother died when he was just ten. His older sister assumed the responsibility of raising him, engendering a close and affectionate relationship that lasted until Ryōma’s untimely death. Much of what we know of Ryōma’s character and perspective on life emerged from the numerous letters he wrote to his devoted sister.

“Revere the emperor, expel the barbarians!”

At age 14, Ryōma’s sister arranged for him to study swordsmanship in their hometown of Tosa, now Kochi City. She hoped it would help him cultivate both physical strength and confidence, aspects that had been lacking due to years of weakness and bullying. The plan proved successful. Three years later, in 1853, Ryōma’s clan granted permission for him to journey to Edo, now Tokyo, to refine his skills, where he ascended to become a master instructor. While practicing swordsmanship in Edo, one can imagine Ryōma had no idea of the impending dramatic changes that would soon unfold in his country, changes in which he would play an intimate and significant role.

In 1853, the American Commodore Perry and his menacing black ships sailed into Edo harbor sending shockwaves throughout the country. His four ships wielded more firepower than the entire shogunate, prompting Ryōma to be summoned to defend the Shinagawa coast. There, he lent his voice to the swelling chorus advocating for Sonnō-jōi, “Revere the emperor, expel the barbarians!”

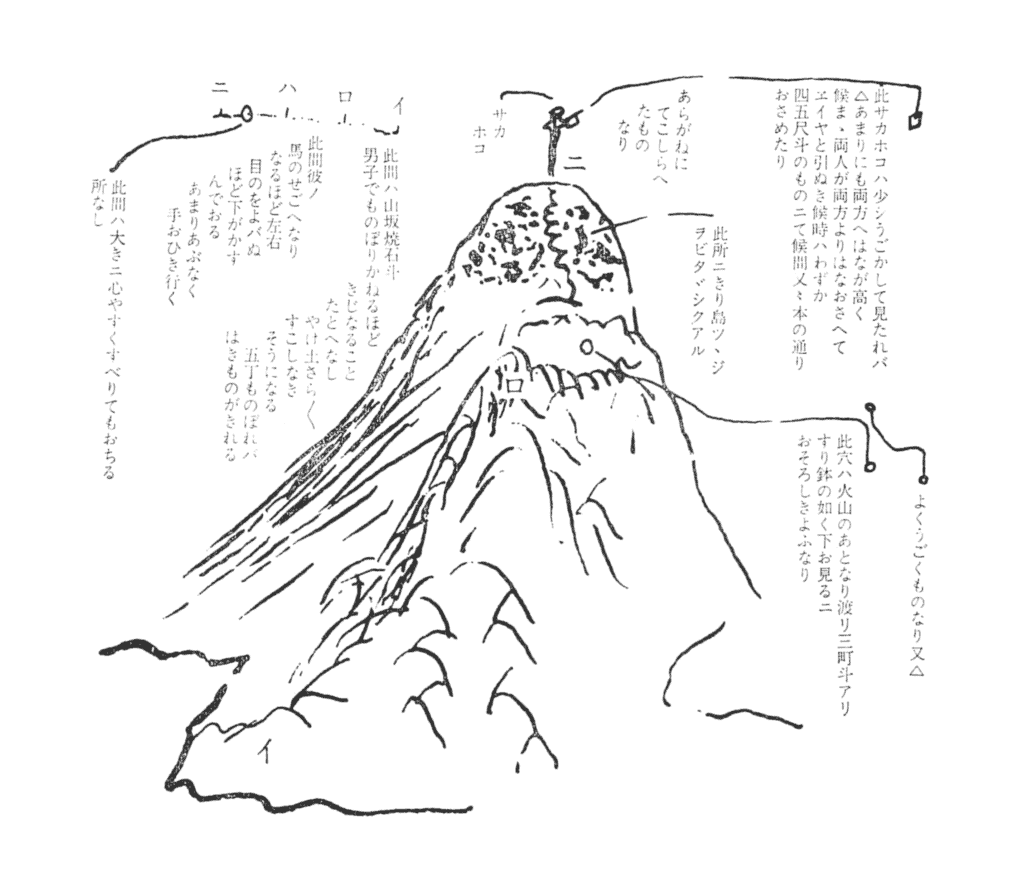

Returning to Tosa in 1858, he met with Kawada Shōryō, an artist well versed in Western ways due to his close friendship with John Manjirō, a castaway who spent 11 years in the United States. Through many conversations with Shōryō, Ryōma’s eyes were opened to the vast technological capabilities of the Western world. Feudal Japan had no other choice but to embrace Western knowledge. “Expelling barbarians” was no longer part of his objective.

When his relative, Takechi Zuizan, formed the Tosa Imperial Loyalist Party, Ryōma was the first to join. The following year, he traveled to Chōshū, now Yamaguchi Prefecture, entrusted with a confidential letter from Zuizan to Genzui Kusaka, a key figure in the Sonnō-jōi movement. During their meeting, Kusaka expressed that under the prevailing circumstances, feudal lords and aristocrats would be unreliable guardians of Japan’s future. Instead, it was time for grassroots individuals, particularly ambitious young men from rural regions like Ryōma, to stand at the forefront of change.

Dappan — Leaving the Tosa Clan

During the Edo period (1603-1867), traveling outside one’s clan necessitated the domain lord’s permission and an official travel permit to be presented at checkpoint barriers. Dappan, leaving one’s clan without permission, was akin to someone today crossing international borders without a passport—but the penalty was death. In the spring of his 28th year, Ryōma took this daring step, leaving the Tosa domain to embrace the life of a rōnin, a masterless samurai.

He first journeyed to areas unlikely to punish rōnin, starting with Chōshū, a hotbed of radical anti-shogunate fervor. From there, he traveled further southwest to the more moderate Satsuma, now Kagoshima Prefecture, where the leaders harbored aspirations of national unity, envisioning an alliance between the shogunate and the dominant feudal lords.

After absorbing these disparate ideologies, Ryōma set his course for Edo. There, he met with Katsu Kaishū, the shogunate’s chief magistrate for warships, who had previously captained the ship sent as the second official Japanese embassy to the United States. Some historians question Ryōma’s intentions, suggesting an assassination plot against Kaishū. Yet Ryōma emerged from the encounter persuaded of the necessity of a plan to increase Japan’s military strength. The rōnin Ryōma became Kaishū’s protégé.

When Kaishū was assigned to patrol the sea around Osaka, Ryōma accompanied him. In the small fishing village of Kobe, Kaishū established the Kobe Naval Training Center to train officers, construct a modern port, and build Western-style warships. There, Ryōma and other rōnin received invaluable training.

On June 5, 1864, growing hostilities between the shogunate and the opposition erupted in Kyoto. Sonnō-jōi shishi (rōnin activists) staying at the Ikedaya Inn were violently set upon by the shogunate’s Shinsengumi police forces. The following day, Ryōma’s house was attacked. The Shinsengumi became ever more bold, indiscriminately arresting anyone from Chōshū.

Chōshū forces rallied with the support of young men from Katsu Kaishū’s Naval Training Center. Tensions flared between Sonnō-jōi shishi and the shogunate forces. Violence escalated. Chōshū forces attacked the Imperial Palace hoping to forcibly restore the emperor to political power only to be defeated by samurai from Satsuma and Aizu, now Fukushima Prefecture. Fires broke out in Kyoto.

Kaishū was summoned back to Edo and dismissed from his position. He spent two years in quiet reading at his estate.

Meanwhile, Ryōma sought refuge at the Satsuma clan’s residence in Osaka. The following year, under the patronage of the Satsuma clan, Ryōma, along with fellow rōnin from the Kobe Naval Training Center, established the Kameyama Shachu, a trading company and naval force based in Nagasaki. Through this venture, they imported Western arms, goods, and ships for the southwestern clans. Ryōma’s ultimate goal was clear—to overthrow the shogunate.

The Satcho alliance — Satsuma and Choshu join forces

Later in 1864, the shogun issued a decree demanding all domains unite for an all-out assault on Chōshū. Satsuma defied this order. The Satsuma leaders Saigo Takamori and Okubo Toshimichi had been shifting away from their previous moderate stance. Disillusioned with Shogun Tokugawa’s increasingly authoritarian approach, they became convinced that toppling the shogunate and establishing a new government under the emperor’s leadership was the only path forward.

On January 21, 1866, Ryōma orchestrated a meeting in Kyoto that brought together Saigo Takamori of Satsuma and Kido Takayoshi of Chōshū. These former foes forged an alliance that overcame the enmity of the past. United by a shared vision of a new Japan, they became a formidable opposition force against the shogunate.

For Ryōma, the price of this mediation was steep. The shogun branded him an enemy of the state, and retribution was swift.

In search of a haven, Ryōma went to stay at the quiet Teradaya Inn in Fushimi, near Kyoto. However, his peace was shattered when shogunate officials raided the inn. Quick thinking by Oryō, a courageous woman who worked at Teradaya, coupled with the aid of a samurai from the Chofu Domain, enabled Ryōma to slip through the fingers of his would-be assassins. Despite sustaining severe hand injuries, he managed to escape to the safety of the Satsuma Clan’s Kyoto residence.

Japan’s first honeymoon

Within the safety of the Satsuma Clan residence, Ryōma was tended to by the gentle Oryō. As the days passed, a deep bond blossomed between them, and they were soon married. At Saigo Takamori’s suggestion, the couple went on a honeymoon to Kirishima in Satsuma—the first honeymoon recorded in Japanese history—where they soaked in the healing hot springs of the mountains, and Ryōma recovered from his wounds.

In the summer of 1866, the shogunate unleashed a second onslaught to punish Chōshū. Ryōma fought for Chōshū aboard his British-built vessel, the Union, sailing under the banner of Kameyama Shachu. The disciplined might of the Chōshū army overwhelmed the shogunate’s forces, dealing a fateful blow to the authority that had long held Japan in its grip.

Formation of the Kaientai

As the echoes of the Chōshū victory reverberated, Ryōma found himself in Nagasaki in January 1867, where he crossed paths with Gotō Shōjirō, the power behind the Tosa domain. Certain that Japan’s progress hinged on dismantling the shogunate, Ryōma recognized the advantage of incorporating Tosa into the Satchō alliance.

Accompanying Gotō to Tosa, Ryōma was forgiven for his crime of dappan, desertion from the domain. He merged his Kameyama Shachu with the Tosa Clan, birthing the Kaientai, “Maritime Support Force,” with Ryōma at its helm. Intended to be a navy for the Tosa domain, it was an unusual organization also engaged in commercial trade and training. Its diverse composition included rōnin, doctors, officials, and even a baker. Many were people with a desire to explore overseas—although leaving the country without permission meant facing the death penalty upon return.

By June of the same year, Satsuma and Chōshū had begun contemplating the use of military force to overthrow the shogunate. Seeking a diplomatic alternative, the Tosa Clan turned to Ryōma for guidance. Aboard a ship heading to Edo with Gotō Shōjirō, Ryōma penned the Senchu Hassaku, “The Eight Point Plan for Imperial Restoration and Governance.” Among its provisions were the critical demands for the restoration of imperial rule and the establishment of a national assembly.

Gotō used his influence to formulate a petition based on Ryōma’s plan that was delivered to the 15th shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu. After deliberation, Yoshinobu assented to their propositions, culminating in the historic act of returning power to the Imperial Court at Nijō-jō Castle in Kyoto on October 14, 1867, bringing an end to Japan’s centuries-long feudal age.

Sakamoto Ryoma’s death and legacy

Just a month later, on Ryōma’s 31st birthday, he was staying at the house of a soy sauce merchant in Kyoto. While relaxing after dinner, the stillness was broken by a late-night knock at the door. Ryōma’s loyal bodyguard, a former sumo wrestler, told the caller to wait while he checked if Ryōma would allow his visit at so late an hour.

When the guard turned to climb the stairs to Ryōma’s second-floor room, the visitor unsheathed his sword and attacked, slashing the guard in the back. He and his accomplices rushed past the fallen guard and stormed into Ryōma’s room where he was talking with his friend, Nakaoka Shintarō. During their chaotic attack, the assassins upended lamps, scattered documents, and tore the paper doors. Following the frantic scuffle, both Ryōma and Shintarō lay mortally wounded. Ryōma died later that night, and Shintarō succumbed two days later. The identity of the assailants remains a mystery.

Since his tragic demise, Sakamoto Ryōma’s popularity has grown, bolstered by the many detailed and illustrated letters he had written to his sister. His remarkable tale has been immortalized in movies, manga, and television series. Although he did not live to see the fruition of his efforts, Ryōma’s central role in mediating the alliance between the Satsuma and Chōshū domains and his drafting of the Eight Point Plan for Imperial Restoration are widely regarded as instrumental in bringing about the Meiji Restoration.

In recent years, the 21st-century tech giant Softbank paid homage to Ryōma’s legacy. They adopted his three-striped Kaientai flag as the inspiration for their logo, symbolizing their admiration for Kaientai’s fervor and alignment with their vision. Ryōma’s influence, it seems, has transcended the boundaries of time, finding resonance in the ethos of a modern era.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/