Where ash-fall is an everyday occurrence

Have you ever wondered what it would be like to live next to—or on—an active volcano? Well, that is what the people of Kagoshima, Japan, experience every day.

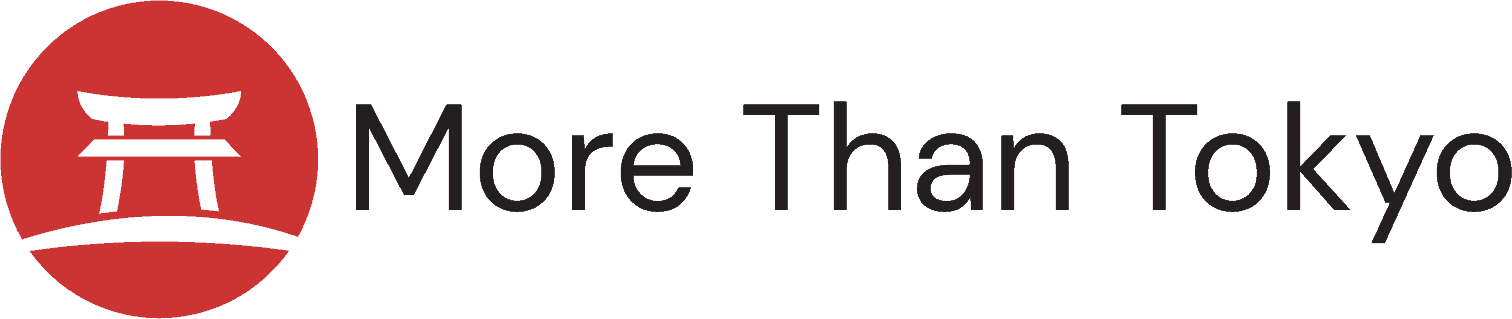

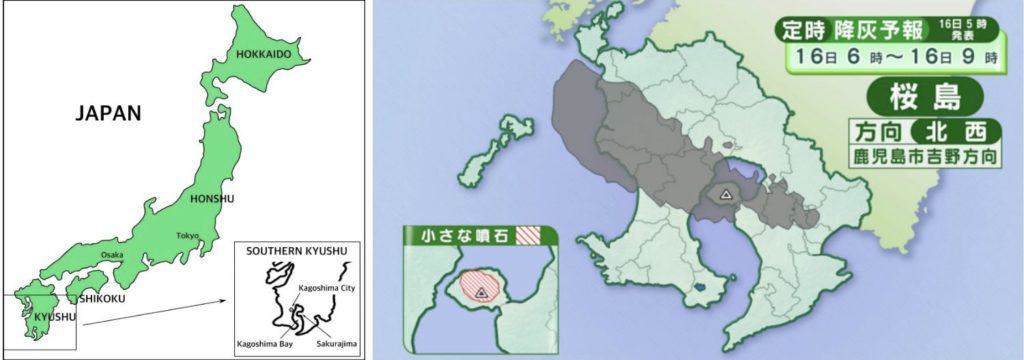

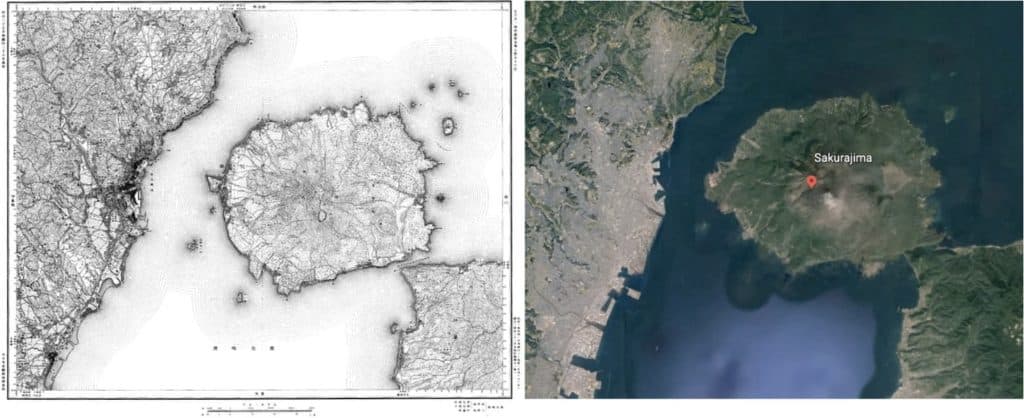

Sakurajima is an active stratovolcano four kilometers across Kagoshima Bay from downtown Kagoshima City, in southern Japan. Although its name means “cherry blossom island,” it is no longer an island as a result of a major eruption in 1914.

Sakurajima is one of the most active volcanoes in the world, averaging over 1,000 eruptions per year from 2009 to 2015. In 2020, it calmed down to a reasonable—for local residents—432 eruptions.

Despite the frequent eruptions, people have lived on the volcano since ancient times. Shell heaps—shells and other discarded food waste—dating from the Jomon Era (14,000–600BC in southern Kyushu) have been uncovered by archaeologists.

Although more than 20,000 lived on the island before 1914, today the population has shrunk to 4,000 inhabitants, primarily due to Japan’s overall population decline that most severely affects rural areas.

The fewer than 100 elementary school children who live on the volcano wear helmets for protection from falling pumice and ash as they walk to and from school.

Residents of Kagoshima City, which includes Sakurajima, sweep up ash daily, fill yellow ash bags provided by the government, and deposit them for removal at collection centers in each area.

An inexpensive ferry makes the 10-minute trip between Sakurajima and Kagoshima City every 15 minutes, so there is plenty of opportunity for higher education, jobs, shopping, or eating out for the inhabitants of Sakurajima.

Living with ashfall

Residents of Kagoshima check the weather report each morning to see the predicted areas of ashfall. Through this, they know whether it will be wise to open their windows, hang laundry, or wash their cars. I’ve learned that washing my car is a sure predictor of ashfall. Wash the car—ash will surely fall the next day and get it dirty again.

When ashfall is heavy, cars use their windshield wipers and residents wear masks and carry umbrellas to keep off the ash. Sweeping up ash is a regular part of life.

Geology

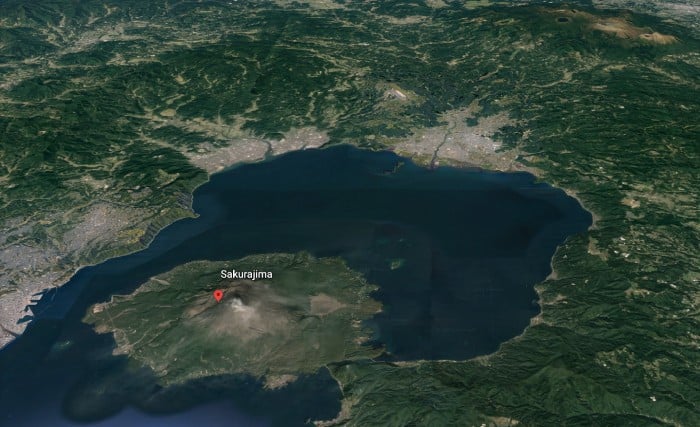

Sakurajima is actually two volcanoes that formed side by side, in a north-south line. It sits on the southern rim of the Aira Caldera, the remains of a huge volcano that erupted approximately 30,000 years ago.

This event is responsible for the deep layer of white pumiceous soil, shirasu, that covers southern Kyushu, as well as for the formation of the northern half of Kagoshima Bay, when the caldera collapsed on itself after the eruption and filled with seawater. Underneath the bay is a large magma chamber that feeds into Sakurajima.

The northern peak (to the left in the pictures) is the oldest and is inactive. Erosion from the northern peak resulted in the formation of a fertile alluvial fan on the eastern side of Sakurajima. In this well-drained soil, the world’s largest radishes and the world’s smallest oranges are grown.

The southern peak is newer, and it is from this side of the volcano that ash, gas, and pumice are regularly spewed.

Taisho Eruption, 1914–1915

On January 10, 1914, Sakurajima and the surrounding areas were shaken by four strong earthquakes. The next day, 250 smaller quakes occurred. The 23,000 people who lived on the island literally felt what was coming. Using whatever boats they could get their hands on, the islanders worked together to evacuate themselves and their farm animals safely to Kagoshima City. The Imperial Navy provided more ships the next day.

At 10:05 on January 12, a fissure opened halfway up the southwestern flank of the volcano facing the city across the bay. Ash, pumice stone, and gas thundered out horizontally, then shifted to spiraling upwards. The roar of this explosion was heard all across the islands of Kyushu and Shikoku. This eruption was soon joined by another opening on the eastern flank of the volcano, violently ejecting ash and gas.

By 11:00, these two plumes had risen five to eight kilometers into the atmosphere, and within days the ashfall had reached all of Kyushu, and as far away as Osaka, Tokyo, and even the Bonin Islands, more than 1,000 kilometers southeast of Kyushu.

On the night of January 12, a 7.1 magnitude earthquake occurred, centered beneath Kagoshima Bay. This quake broke the seismograph in Kagoshima City, collapsed houses, caused a tsunami, and killed 35 people. Ash and pumice continued falling.

Yet another large earthquake occurred on January 13, bringing with it lava flowing from both east and west vents. Along with continued ash and pumice eruptions, lava flowed for months, burying fields and villages, shallowing Kagoshima Bay, and covering nearby islands.

As the flow continued, parts of the bay heated to more than 750°C, cooking fish and other sea life. Rafts of pumice stones intermingled with dead sea creatures bobbed on the surface and washed up on the shore.

By January 13, the people of Kagoshima City had also been evacuated. Aid came from the Japanese government and other nations. The destruction that was caused by the volcano was significant, although few lives were lost.

Through the months of ash and pumice fall, large areas of farmland were buried, thousands of buildings were destroyed, and people’s livelihoods were shattered.

With the wind blowing from the west, houses on the Osumi peninsula, east of the volcano, were buried up to the roofs in ash. Many houses in Kagoshima City to the west that had survived the 7.1 magnitude earthquake, collapsed under the weight of the ashfall.

By early April 1914, Sakurajima was no longer an island. The lava flow had filled in the Seto Straight that had divided Sakurajima from the Osumi peninsula, connecting the island to the mainland.

Eruptions continued sporadically, decreasing in frequency over the next year. By November 1915, the volcano was quiet. The residents of Sakurajima were provided with money by the government, and more than half of them returned to their ancestral homes.

After the eruption subsided, it was discovered that the entire area had sunk about 60 centimeters—in some places, as much as a meter. The lava that had been stored under the bay in the magma chamber of the Aira caldera had been released and the land above it sunk.

Preparing for the next big eruption

Knowing that future eruptions are inevitable, local and national governments have taken steps to try to lessen their impact and improve early warning capabilities.

Canals for channeling mudslides and lava have been built on the slopes of Sakurajima, and each January, evacuation drills are held for the entire population.

The tiniest rumblings, changes in the volume of the magma pool, and increases in the size of the volcano are carefully monitored by high-tech equipment on Sakurajima. The data is analyzed by specialists in Kagoshima and at Kyoto University, and appropriate warning levels are announced.

That said, the amount of magma stored beneath the Aira caldera is now reaching the level it was before the 1914 eruption. Volcanologists are predicting that in the near future, the possibility of another large-scale eruption is high.

How would you feel about living on or near an active volcano?

All photos ©Diane Tincher unless otherwise specified.

Sources:

Sakurajima eruption data, population statistics, Taisho eruption, more on the Taisho eruption, geology, general information from Sakurajima Visitors’ Center, and 26 years of living in Kagoshima City.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/