Wild vegetables, or sansai, play an important role in Japanese cuisine

Washoku, Japanese cuisine, is a celebration of seasonal dishes, and sansai, 山菜, wild mountain vegetables, play a starring role. Elderly folks have told me of the long-held belief that whatever foods are in season are what our bodies require at that time of year for optimum health. Surely, that holds true for sansai.

On my late afternoon springtime walks, I can find lots of sansai, the same as you might be served at inns or local restaurants.

Join me, as I walk around my neighborhood.

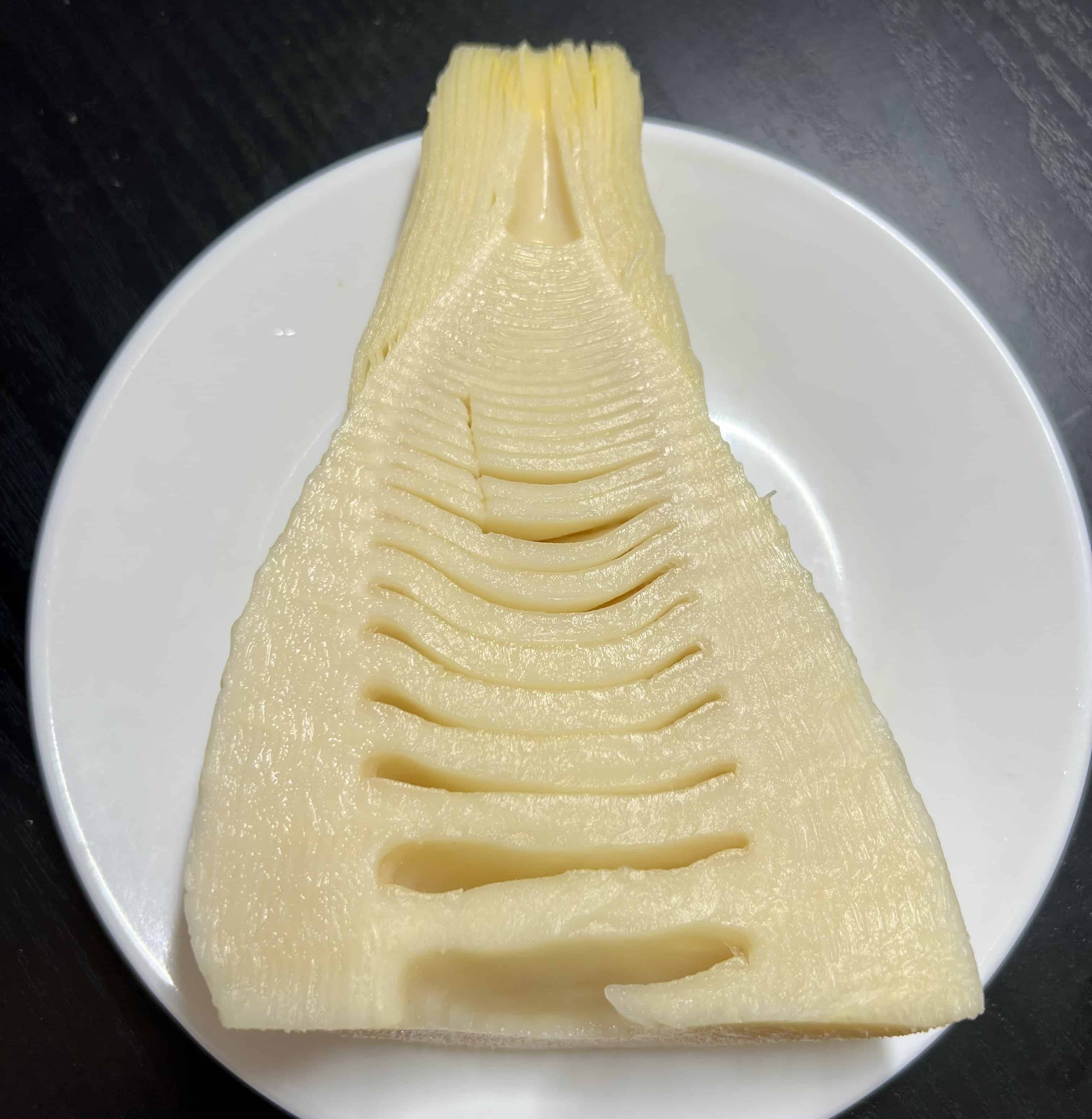

Bamboo shoots

The first thing to catch my eye not 50 meters from my house is a bamboo shoot, although far past its time for harvest.

If you want to try one yourself, don’t make the same mistake we did. These fast-growing plants need to be cut from the ground at first sight of the tiny tip breaking through the soil. Otherwise, they are too tough to eat.

Once you dig up a shoot, peel off the outer layers, then boil the heart in water with salt or a little nuka rice bran to remove its astringency.

Bamboo shoots are a crunchy addition to rice dishes like chirashizushi and takikomi-gohan, and I chop and freeze some to use out of season. Like pretty much every other vegetable in Japan, they are often added to soups. I’ve also had them made into tempura, or boiled with root vegetables in soy sauce, sake, and sugar.

Called “green gold” in India because of their nutritious value, bamboo shoots are rich in fiber and low in calories, they are a good source of vitamins A, B6, and E, potassium, manganese, thiamine, and niacin.

Next, all I had to do was turn around, and I spied a field filled with horsetails.

Horsetails

In the spring, horsetails are the first sansai, and they pop up everywhere. Their little leafless sprouts have a cute Japanese name — tsukushi, 土筆, a paintbrush 筆, coming out of the ground 土.

People stop by the road to gather them and bring them home to blanch, then prepare with a miso/vinegar sauce, or scramble them with eggs, or perhaps pickle them to be eaten throughout the year.

Some people claim that horsetails can treat urinary tract infections, edema, kidney stones, and rheumatism. Others say they help skin conditions and can even aid hair and nail growth.

But I am not a practitioner of herbal medicine. I just enjoy a horsetail or two when served as part of a traditional Japanese meal.

I turn from the horsetails, walk down the hill, and come upon the third sansai of this walk.

Angelica

My favorite path meanders through rice fields and vegetable gardens. As I am walking, a man calls out to me from where he stands beside some very tall plants. He’s cutting the tips off fresh sprouts.

He tells me that these plants are not native to our area, but a friend in Nagano gifted them to him. He waxes eloquently about the deliciousness of tara no mi and insists I take some home and tempura them for dinner.

I did just that, and they were indeed delicious!

I later learned that tara no mi are angelica tips, a favorite among herbalists, and realized I’ve often been served it at inns in Nagano.

Angelica is used as a tonic for the nervous system, to treat digestive issues, respiratory infections, and menstrual cramps. This website claims it has anti-anxiety effects. I can’t say I’ve noticed any of these effects.

But my walk isn’t over. I follow the stream to another area of paddies, up a hill by greenhouses made of plastic sheeting, and down a disused path. Along the side, I spy our next sansai.

Butterbur buds

Butterbur has a long history of medicinal use.

The 1st century Greek, Pedanius Dioscorides, is said to have used a paste made from powdered butterbur to treat skin ulcers. In 17th century Germany, powdered butterbur root was used to treat sudden abdominal pain, asthma, and colds. In the 18th century, that same powder was used to treat plague victims.

Today, herbalists use butterbur to treat migraines, colds, hay fever, inflammation, and more.

Butterbur buds, or fuki no to, 蕗のとう, are almost as common as horsetails. They are best picked when they first appear, and the buds are still closed. They can be sauteed and mixed with miso paste or fried in tempura. Not only are they delicious, but they are full of vitamins, minerals, and fiber.

I think this next one is my favorite, but I wonder, is it really sansai? It seems to me to be cultivated.

Baby mustard greens

Baby mustard greens, or baby bok choy, is a tender, sweet leafy vegetable. The local elderly folk who keep gardens often put out bundles to sell, and that’s where I’ve gotten mine.

Like all sansai, they are best eaten fresh. Use them raw in salads, stir-fry with garlic, or add to soup.

They are low-calorie, full of fiber, and rich in vitamins A, C, and K, calcium, iron, potassium, and trace minerals. They also contain cancer-fighting antioxidants and prevent inflammation.

And I just thought they were a delicious spring treat!

As I walk through the rice fields, this last sansai is everywhere.

Chinese milk vetch

Chinese milk vetch covers most of the rice fields in my area each spring and, I’ve been told, is a boon to rice farmers. It has lovely Japanese names, rengeso, 蓮華草, lotus flower grass, or genge 紫雲英, purple clouds. When in full flower, the plants are turned under to provide needed nitrogen to the soil.

A field covered in purple Chinese milk vetch is a field that will produce a bountiful crop of rice, or so the farmers assure me.

Leaving the rice fields behind, I hike back up the hill to my house, refreshed and revitalized from my daily walk, taking in the beauty of nature.

I hope you can try some of these sansai if you haven’t yet. Do you have wild vegetables in your area?

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/