Wreaking Havoc in Tokyo from the 10th Century

Japan loves threes. Three Great Beautiful Places. Three Great Night Views. Three Great Mountains. In this three article series, I will introduce to you Japan’s Three Great Vengeful Ghosts.

The Japanese people have long believed in ghosts, hauntings, and spiritual realms. People generally will not move into a house or apartment where someone has died, and there is at least one website that lists such haunted residences to warn potential buyers. Television shows that recount ghost stories are a standard of prime-time viewing.

So please allow me to introduce you to the most famous ghost in Japan, who just happens to haunt Tokyo.

Vengeful Ghost #1 — Taira no Masakado

In the early 10th century, the powerful samurai warlord, Taira no Masakado, staged various uprisings near the northern border of the Japanese state. Far away in the capital of Heian-kyo, now Kyoto, the emperor yawned and turned back to his tea. No need for the son of heaven to bother with petty local skirmishes.

A few years later, though, the situation became more serious. Masakado had captured the governor of Hitachi Province (Ibaraki Prefecture) and taken over Shimotsuke and Kōzuke (Tochigi and Gunma Prefectures). He then proclaimed himself the “New Emperor.”

Time to put down that teacup.

Emperor Suzaku placed a bounty on his head and sent an army to hunt down the arrogant Masakado.

The wily Masakado was hard to corner, but after weeks of pursuit and battles, the final showdown came.

With a strong north wind on his back, Masakado held the advantage. Nevertheless, the imperial forces felt confident in their superior numbers and launched a surprise attack on Masakado’s center. An intense battle raged. Masakado’s samurai repelled the enemy with horses racing, arrows flying, and spears thrusting. Men and horses scattered, and 2,900 of the emperor’s samurai were forced to retreat. Just 300 of their elite warriors remained.

Proud of his victory against a much larger force, Masakado was making his way back to camp when he felt the wind change. He readied himself for another battle.

Using the south wind to their advantage, the remaining imperial samurai quickly regrouped and sprang to the attack.

Masakado charged to meet them, but his fleet-footed horse lost its footing on the uneven ground. In that one moment of Masakado’s distraction, an arrow pierced through the middle of his forehead.

The imperial samurai severed Masakado’s head and brought it back to the capital to present to the emperor. Setting a new precedent in criminal law, Masakado’s head was put on public display in Kyoto’s marketplace as a grisly warning. Worse, the emperor expressly forbade that his remains be given a Buddhist burial or memorial service, condemning his spirit to wander this earthly realm with no hope of redemption.

This is when the rumors started.

Birth of a Vengeful Ghost

Some people reported seeing Masakado’s eyes open while his head was displayed.

A poet recorded he saw Masakado’s head turning left and right, groaning and looking for his body, whereupon his head broke away and flew off north in search of it.

Masakado’s head came to rest in the tiny fishing village of Shibazaki, later to become Edo, then Tokyo. The locals cleaned it and provided it with a proper burial at Kanda Shrine, inscribing his gravestone with prayers to keep Masakado’s troubled spirit appeased.

Yet each time unexplained trouble occurred, the villagers believed it was caused by the angry spirit of Masakado.

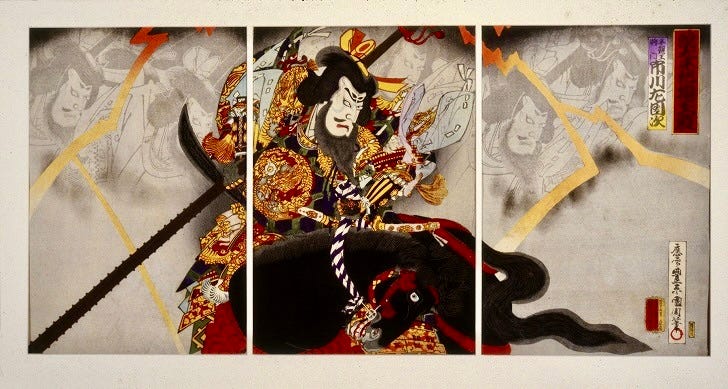

During the Edo era (1603–1867), Taira no Masakado grew in fame as Kabuki theater, woodblock prints, and books for the masses grew in popularity. Masakado’s ghost became a recurring theme in entertainment for the superstitious public, and even his daughter came to the fore. A famous Kabuki play portrayed her as a powerful sorceress, fighting off imperial pursuers with witchcraft.

Trouble at the Ministry of Finance

In the late 1800s, Kanda Shrine moved to its present location. The Ministry of Finance took over its former area, sharing its grounds with Masakado’s tomb. Each year, Masakado was treated with ceremonies as befitted a lord. A portable shrine was carried from Kanda Shrine, and priests prayed for the repose of his spirit. Masakado seemed pleased.

During the devastating Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 and its resultant fires, the Ministry of Finance building burnt to the ground. Remarkably, although reduced to a bald mound of earth, Masakado’s underground tomb remained intact. Archeologists discovered that his tomb was built in the ancient keyhole style of the Kofun era (300–600 AD) and were keen to preserve it.

Sadly, there were no laws in place to protect historical properties, and within two years, the land was leveled. A temporary building to house the Ministry of Finance was constructed in its place.

That couldn’t be good.

Before two more years had passed, 14 people in the finance ministry had died under mysterious circumstances. Even the Vice-Minister of Finance, Hayashi Seiji, passed away after a brief and unexplained illness. People who worked above the former grave sight complained of pains in their feet.

Their disrespect for Masakado was deemed the cause of all these troubles.

Apology to a Ghost

“Even in this modern age of progress and science, bureaucrats apologize to Taira no Masakado,” reported the Yomiuri Newspaper in 1926.

The building that had been constructed upon Masakado’s tomb was torn down. Shinto priests were called in to perform a purification ceremony and to pray for the repose of Masakado’s soul. A hedge, a stone lantern, and a monument were erected in the hopes of appeasing his troublesome spirit.

Perhaps he would like the little garden offering?

Lightning Strike

In 1940, one thousand years after Masakado’s death, fires caused by lightning destroyed the Ministry of Finance and nine other adjacent government buildings. Kawada Isao, the Minister of Finance, hoping to undo the damage, erected a monument upon the exact spot of Masakado’s tomb that had been so thoughtlessly destroyed after the 1923 earthquake. A Shinto ceremony marking the 1,000th anniversary of Masakado’s death was held to comfort his spirit.

WWII and its Aftermath

During the firebombing of Tokyo in March 1945, the area around Masakado’s tomb was again burnt to the ground, but the monument remained relatively unscathed.

After the war, the Americans, unaware of the danger posed by angering the spirit of Masakado, bulldozed the area to make a parking lot. According to records at the Kanda Shrine, the bulldozer flipped over, killing the driver.

Members of the local community were appalled at the Americans’ actions. Fearing further retribution from Masakado, the community leader petitioned the Occupation Forces to allow them to preserve “the grave of an ancient great chieftain.” Their request was granted and the local people adopted the gravesite, keeping it clean and offering flowers and prayers.

From Vengeful Ghost to Shinto God

In 1984, Taira no Masakado’s reputation took a turn, and he became one of the three kami, or deities, enshrined at the Kanda Shrine in Tokyo.

The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, located in the building beside Masakado’s grave, opened an account in his name. Money placed into the donation box at his gravesite — to the tune of 800,000 yen per year ($7,000) — is kept there to be used for gravesite maintenance and care.

Although the monument — built in 1940 upon the spot where Masakado’s head was buried so many years before — today occupies prime real estate in downtown Tokyo, it is still carefully preserved, honored, and respected. You can find it near Otemachi Station, a stone’s throw from the Imperial Palace.

Why not stop by and pay your respects on your next visit to Japan?

P.S. Frogs

Until its 2020 renovation, Taira no Masakado’s grave was surrounded by many frog statues. In Japanese, both “frog” and “return home” are pronounced kaeru. Masakado’s head came to rest there because of his quest to “return home” to his body. People wishing for the safe return of missing loved ones, and people going on trips who wanted Masakado to bring them back home safely, placed frog statues around his grave as an offering of prayer.

Today, to keep the gravesite tidy, those frog statues have been moved to Kanda Shrine and can no longer be viewed by the public, nor can any more be given as offerings. A spokesman for the shrine said, “In these days of increased concern about hygiene, please refrain from leaving things at the shrine.”

Links to the stories of the other two great vengeful ghosts:

Ghost #2, Emperor Sutoku, and ghost #3, Sugawara no Michizane.

Sources:

https://skawa68.com/2021/06/16/post-74501/, https://mag.japaaan.com/archives/102341, https://sakamichi.tokyo/?p=15968, https://www.goshuinbukuro.com/entry/2017/08/16/233000, https://bit.ly/34fTakP

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/