English whalers’ demand for beef has dire consequences

My dear friend’s father, Ed, was an American officer involved in training Japanese pilots in the 1950s for the nascent Japanese Self-Defense Force. During his years in Japan, he became friends with the descendent of a well-placed samurai family, Mr. Takahashi. This gentleman had been spending his retirement making scouting trips to the Philippines, searching for the bones of his fallen countrymen to bring home. He strongly felt that their spirits deserved to rest in their native land.

Perhaps inspired by his missions, one day Takahashi invited Ed to visit his family’s ancestral home where his elderly mother still lived. They bowed to his family’s matriarch, and then Takahashi sought her permission to present something to Ed.

She consented.

Takahashi pulled out an antique wooden chest. He opened the heavy lid and lifted out a cloth-wrapped bundle.

He entrusted the bundle to Ed, asking him to please bring its contents back to the West. Takahashi told Ed that he felt the fallen man’s spirit within should be returned to his homeland.

The items in the package were extraordinary. They were the relics of an obscure but pivotal event that occurred in 1825 on a tiny island in southern Japan: scrolls, illustrations, and a packet of human hair.

Background on the Japanese diet

Until the late 1800s, the Japanese had never eaten much meat. Because of the Buddhist belief in reincarnation, in 675 AD, Emperor Tenmu proclaimed a ban on eating mammals. Aside from that, the mountainous geography of the country was simply not suitable for raising livestock.

The traditional diet consisted of rice served with vegetables, and sometimes fish, poultry, and perhaps game. Horses and cattle were used exclusively as farm animals and were considered expensive and precious commodities.

In contrast, the people of European descent have been raising livestock and eating meat for millennia.

Edo Japan’s policy towards foreigners

In 1638, the 3rd shogun of the Edo era (1603-1867), Tokugawa Iemitsu, quelled a major uprising in the southern province of Nagasaki. Though many factors contributed to the revolt, the recently introduced and novel Western religion of Christianity had played a leading role. Iemitsu ordered the massacre of thousands of Christians and rōnin (masterless samurai), brutally destroying the rebel faction.

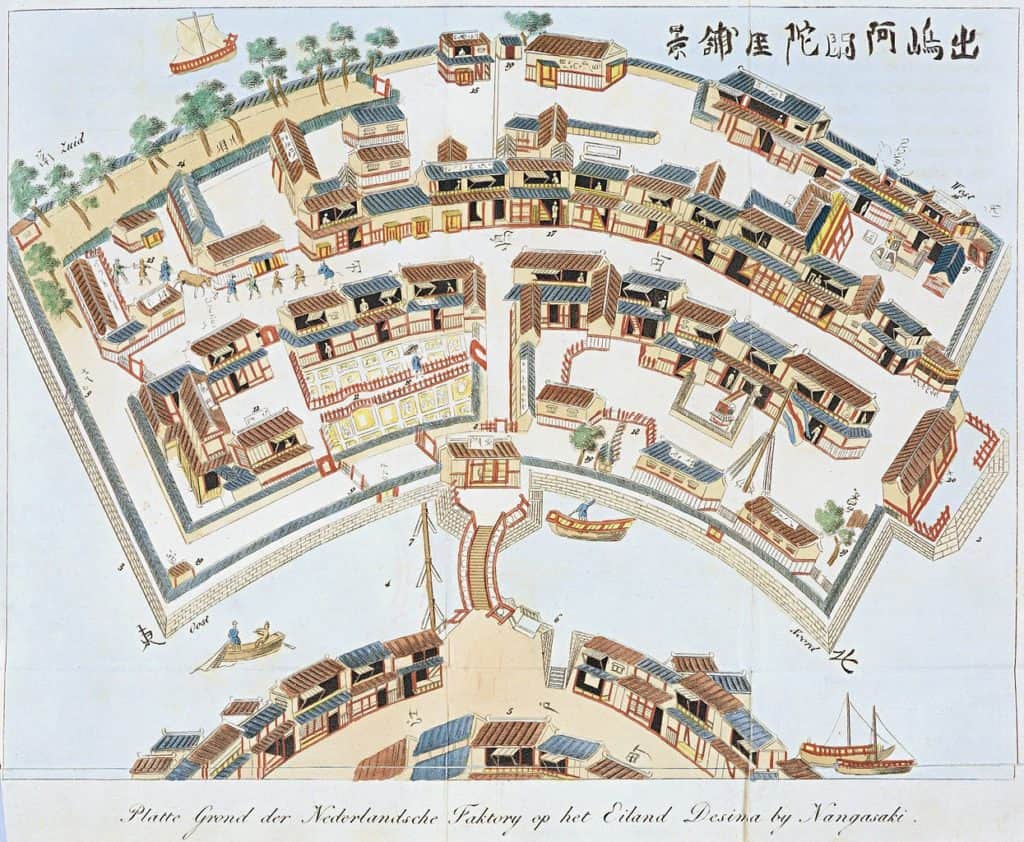

The following year, Iemitsu dictated that all contact with the West be severed, save for tightly controlled trade with the Dutch who were relegated to the man-made island of Dejima, off the Nagasaki coast. Involvement with Christianity was punishable by death.

From that time onward, few, if any, Western ships were sighted on the waters around Japan.

This changed in the early 1800s when European whaling ships spent long months hunting in the northwest Pacific. Gone for years from their native lands, these sailors suffered from scurvy and other diseases, and they were often in dire need of fresh food, water, and fuel.

The shogunal policy at the time permitted locals to provide foreign ships with food and fuel as humanitarian aid, but the foreigners were not allowed to set foot on Japanese soil, nor were Japanese allowed onto their ships.

Japanese fishermen occasionally encountered Western ships at sea and sometimes boarded them to explore and trade, regardless of the shogun’s dictates. Western whaling ships began to send landing parties to shore carrying trinkets and clothes to trade for the supplies they needed.

Villagers, after getting over their initial shock at seeing the big, red-haired, smelly barbarians, generally provided the sailors with plenty of fresh fruit, vegetables, rice, poultry, and fuel.

The Takarajima Incident

The tiny island of Takarajima, 宝島, or Treasure Island, is located midway between Kagoshima, in southern Kyushu, and Okinawa. With an area of only 7.14 km², it has long been a quiet home for fishermen and farmers.

On July 8, 1824, an English ship anchored offshore. A landing party made their way to the port. They found the village administrative office, and through gestures and drawings, asked if they could buy one of the cows they had spied on a nearby hillside. The official communicated that they would give them vegetables and water, but no cows. The men returned to their ship.

The people of Takarajima were not rich. They had few cows, and they were treasured.

They also had no guards, but a few low-level samurai families had kept their 16th century matchlock rifles from the Sengoku era. There were seven on the island.

The next day, a party of men came from the ship, this time armed with rifles and bird guns (shotguns). One group stormed a farm, killing one cow and grabbing a couple of others. Another group menaced the village office, firing their bird guns and causing a commotion.

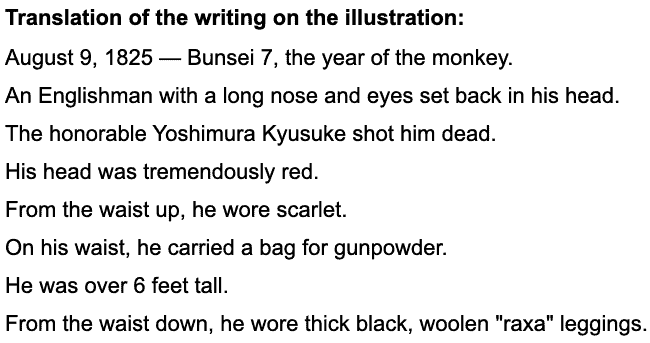

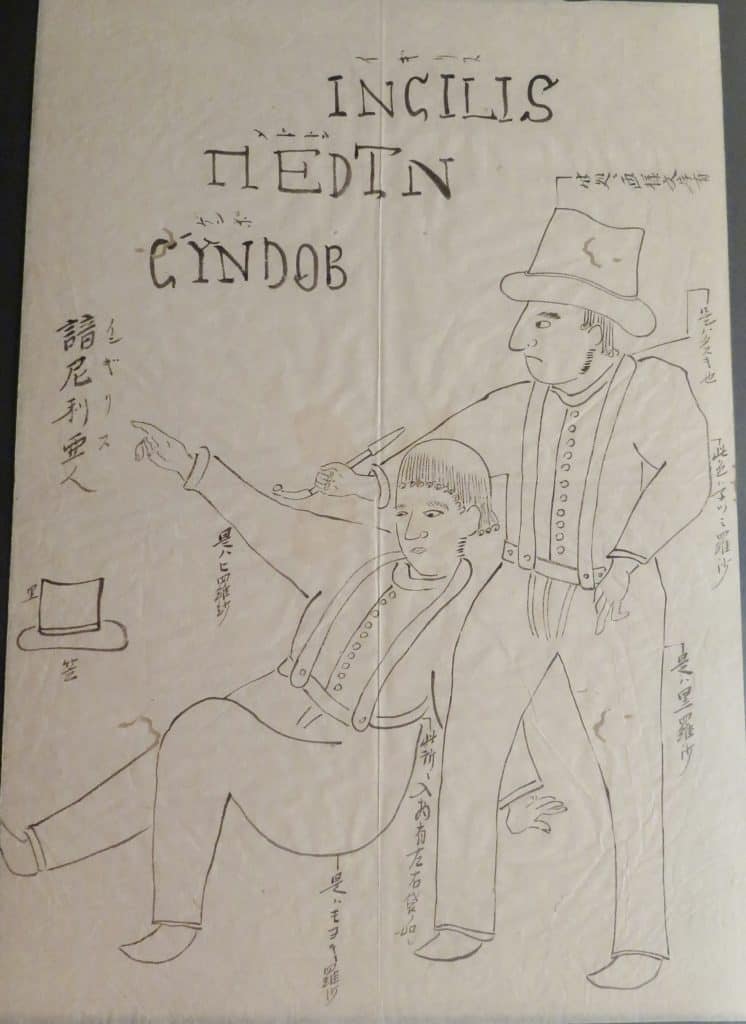

At that time, Yoshimura Kyusuke, 吉村九助, a samurai from the Satsuma domain headquarters (now Kagoshima City) was visiting. By virtue of his position, he carried a well-maintained rifle. He took aim at an Englishman and fired, striking the leader of the landing party.

When his countrymen saw him fall, they left him and rushed to their boat. This was far more resistance than they had expected. Once back to their ship, they raised anchor. For several days the ship circled the island, but no more landing parties were sent.

No islanders were hurt, but three of their precious cows lay dead.

Report to the shogun

The samurai Yoshimura made a full report of this incident to be sent to officials in Nagasaki, who passed it on to the shogunate in Edo (Tokyo).

An illustration was made of the Englishmen, with a detailed description of his appearance and clothing. A lock of his hair was cut and placed in an envelope. The Englishman’s body was packed in salt. All these were sent with Yoshimura’s report and eventually reached the 11th shogun, Tokugawa Ienari.

(photo ©diane tincher)

The Ōtsuhama Incident

The shogun, Ienari, had heard other reports of foreign incursions. In 1824 in Ōtsu, about 150 km north of Edo, a party of 12 English whalers came ashore asking to trade for much-needed supplies. The villagers were fascinated by these strangely dressed hairy men, and a crowd quickly gathered around them. People offered them food and water. Others tried to barter with them for the coins and cloth the men carried. When the village headman arrived, the whalers peacefully allowed themselves to be detained in a small house by the sea.

Messengers were sent to the domain lord, and the next day the first groups of officers and troops arrived. Officials feared that the whalers were a scouting party for an invasion, and within days, several hundred men had gathered to secure the area.

The whalers would remain in Ōtsu for two weeks and be questioned by the local authorities, emissaries from the domain lord in Mito, and even officials from Edo. They were finally able to convince their captors that they were what they claimed to be — whalers in search of supplies. Contrary to the suspicions of the Japanese, they had no intention of spreading Christianity or of conquering Japan.

In the end, they handed over their trade goods — coins and woolens — and returned to their ships with a generous supply of fruit, vegetables, chicken, sake, and more.

Although this encounter ended peacefully, it still served as an annoyance to the Japanese government. The shogunate was torn as to how to respond to the increasing number of foreign landing parties. What if villagers befriended the foreigners? Westerners were Christians. What if someone shared their faith and the contagion spread among the locals? Where would it end?

When Ienari heard of the blatant piracy on Takarajima, he knew he must act before another attack occurred that could erupt into a major conflict.

(photo ©diane Tincher)

Edict to Repel Foreign Vessels

In 1825, Tokugawa Ienari issued the “Edict to Repel Foreign Vessels.” Foreign ships spotted offshore should be fired upon without second thought. Under no circumstances were foreigners allowed to land. No provisions would be provided.

This edict was harmful to many, not the least of which were Japanese castaways who could not be repatriated.

Seventeen years later, when the 12th shogun, Tokugawa Ieyoshi, heard of the humiliating defeat of the Qing Chinese in the Opium Wars, he woke up to the overwhelming strength of the British Navy. Fearing a possible confrontation with Western powers, Ieyoshi repealed the edict in 1842 and encouraged his people to once again provide food and fuel to visiting foreign ships.

Japan’s desire for isolation was forcibly ended shortly thereafter with Commodore Perry’s use of “gunboat diplomacy” in 1854.

Mr. Takahashi passed away years ago, and we have no way of knowing how the illustrations and packet of hair made their way to his family chest.

References

Foreign Encounters and Informal Diplomacy in Early Modern Japan, David L Howell, 大河姫の館, The Meat-Eating Culture of Japan at the Beginning of Westernization, Watanabe Zenjiro, Professor William Steele.

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/