Let me give you 5 reasons, starting with its history

Like many other Americans, I studied French in school. Sure, there were male and female words, a few odd quirks that differed from English, but all in all, it was relatively easy to learn.

So what made learning Japanese so incredibly hard for me? In order to answer that question, we will first need some history.

A Little History of Written Japanese

In the 6th century, along with Buddhism, a system of laws, and many other things, Japan imported its writing system from China.

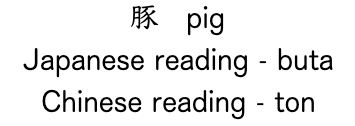

Naturally, Japan already had a language, so these imported Chinese characters — called kanji, 漢字, literally “Chinese characters,” in Japan — were used to represent words that already existed in spoken Japanese. Taking this into account, the ancient scholars of Nara decided that kanji should be read with both the Japanese and the Chinese pronunciations, depending on context.

The problem was that Japanese and Chinese grammar were completely different. Japanese is an agglutinative language, meaning it is short on subjects and long on verb endings which are added to give nuance and meaning to the sentence and to clarify the subject. Put simply, instead of a sentence consisting of subject plus verb like in English or old Chinese, in Japanese we have a verb plus suffixes and add-ons.

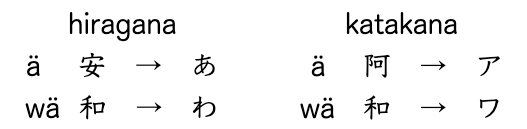

In order to accommodate this difference, the Nara scholars needed something to represent the sounds of those verb add-ons, particles, and other grammatical tidbits. So in addition to kanji used for words, they started using kanji to represent phonetic sounds.

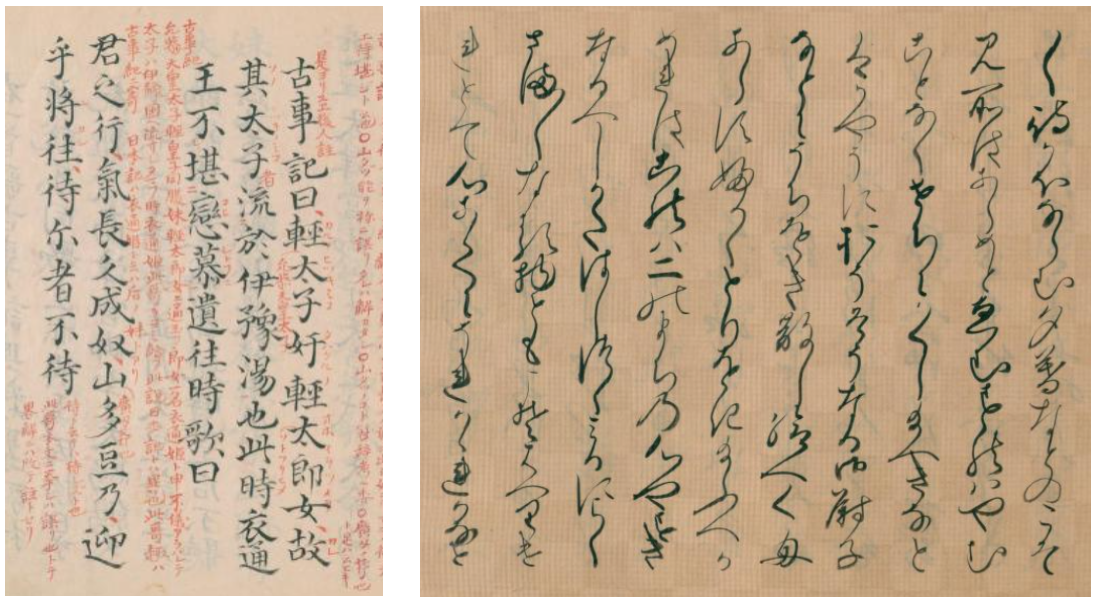

Using kanji simply for their phonetic sounds was called Manyōgana, and the first classical Japanese books were written in this form.

Complicating matters further, in some writings, a sentence would contain kanji used for their meanings and other kanji used only for their phonetics. At first, it was not standardized. That must have been very hard to read. Which was the word and which were the characters being used for phonetics?

As the years passed, writing out complex characters just for their phonetic pronunciation got to be a bit tiresome. So the ladies of the Heian (Kyoto) court developed a simplified cursive writing style for kanji which gave birth to the hiragana alphabet.

The world’s first novel, the Tale of the Genji, and the book of essays, The Pillow Book, are Heian era classics written by such courtly women.

In men’s more formal writing, bits of kanji were used to represent phonetic sounds, which became the katakana alphabet.

Hiragana and Katakana

Memorizing the two phonetic alphabets, hiragana and katakana, is the first step in learning Japanese. They are taught in kindergarten and again in the first year of elementary school.

Nowadays, hiragana is generally used for Japanese words and grammatical add-ons, and katakana is used for loanwords from languages other than Chinese.

Children’s books have these phonetic symbols written beside the kanji that the children have not yet learned. The country follows an official curriculum, so learning kanji is standardized by grade level. After nine years of study, a child should be able to read the newspaper.

Kanji — the Queen of Challenges

There are 2,136 kanji designated by the Japanese Ministry of Education as “characters used in daily life,” as well as thousands more less-familiar ones. These thousands of kanji have been adapted and changed through the centuries, and they no longer necessarily resemble their Chinese antecedents.

Some kanji are easy. 山, read yama, mountain. It even looks like a mountain. Simple.

Some are not so easy, like this, 鬱, utsu, meaning depression. With a stroke count of 29, struggling to write it correctly can truly be depressing.

Some kanji are simple but have different readings, like 生, meaning life, genuine, birth, raw, or even draft, when speaking of beer. According to my dictionary, it has 27 different readings!

How to Read Kanji

Loosely speaking, when a character stands alone it is read with its Japanese pronunciation. When it is together with other characters, it is read with its inherited and adapted Chinese pronunciation.

Take, for example, the word for the first light in the sky at dawn, or its metaphorical meaning, a ray of hope in the midst of despair — 曙光, shokō, its Chinese reading.

曙 by itself is read akebono, meaning daybreak. 光 by itself is read hikari, meaning light. Those are their Japanese readings.

Curious Kanji

Kanji words can bring up marvelous mental images.

稲妻, inazuma, means lightning. It uses the kanjis for 稲 “rice plant” and 妻 “wife.” The wife of a rice plant = lightning.

Or one of the words for a snowflake, 雪花, yuki-bana. “Snow flower.” And the word for snow flurries is just as cute, 風花, kaza-bana. “Wind flowers.”

Or perhaps my favorite, the word for seahorse, 竜の落とし子, tatsu-no-otoshigo. “Bastard offspring of dragons.”

Before I leave the topic of kanji, allow me to introduce you to one of the more stroke-heavy characters.

This amazing work of art is the character, bonnō, meaning worldly desires. According to Buddhist teachings, man is tempted by 108 desires. Many of those desires are represented in this character, which takes 108 strokes to write.

Four Big Challenges in Spoken Japanese

Now let’s take a look at some of the difficulties in mastering spoken Japanese.

Context

Depending on who you are speaking to, whether they are above you in social status, the same, or beneath you — generally someone younger— you use different verb endings, or even different words altogether.

Perhaps you are familiar with the Japanese custom of exchanging business cards when first meeting. Doing so helps one to know what language is appropriate to use with that person.

Keigo (pronounced kay-go)

This is very polite language that is used when addressing someone above you or older than you. It is hard. Help desks use it when I call for help. The 90-something-year-old owner of the seniors’ home where I teach uses it.

When I am spoken to using keigo, if bowing and smiling isn’t sufficient, I ask them to please use more casual Japanese so my head does not explode.

There is another courtly type of polite Japanese used by the imperial family. In fact, when Emperor Hirohito gave his historic speech announcing the Japanese surrender that ended WWII, only the highly-educated could understand his imperial language. This caused a few unfortunate misunderstandings.

Culture

Culture is essential in learning any language, and none more so than Japanese. “Reading the air,” to borrow a Japanese expression, and noting what was left unsaid, is a crucial communication skill.

Japanese people are self-effacing, ambiguous, and indirect. Having a knowledge of Japan’s history and how its culture developed is essential to understanding the whys of the Japanese language.

Negatives

In English, we consider using two negatives in a sentence a no-no.

Not so in Japanese. My doctor was explaining my test results last week, and he used four negatives in one sentence. That’s a lot to keep track of!

But that is normal, and even more normal for polite speech.

Thankfully, the doctor was kind enough to repeat the information in one short simple sentence, with 1/20th the word count.

A Final Word on Learning Japanese

With all these hurdles to conquer — kanji, context, keigo, culture, and all those negatives in one sentence — I doubt I will ever become truly fluent in Japanese. But I will certainly keep trying!

If you have questions about Japan or suggestions for articles, please add them in the comments. For more photos and information on Japan, follow me on instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/more_than_tokyo/